- Home

- Ellen Datlow

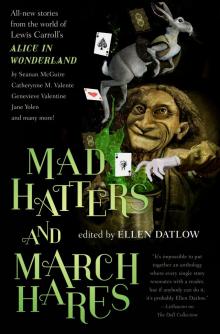

Mad Hatters and March Hares

Mad Hatters and March Hares Read online

Begin Reading

Table of Contents

About the Editor

Copyright Page

Thank you for buying this

Tom Doherty Associates ebook.

To receive special offers, bonus content,

and info on new releases and other great reads,

sign up for our newsletters.

Or visit us online at

us.macmillan.com/newslettersignup

For email updates on the author, click here.

The author and publisher have provided this e-book to you without Digital Rights Management software (DRM) applied so that you can enjoy reading it on your personal devices. This e-book is for your personal use only. You may not print or post this e-book, or make this e-book publicly available in any way. You may not copy, reproduce, or upload this e-book, other than to read it on one of your personal devices.

Copyright infringement is against the law. If you believe the copy of this e-book you are reading infringes on the author’s copyright, please notify the publisher at: us.macmillanusa.com/piracy.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Priya Sharma, for suggesting organizations that might take an interest in Alice.

To my contributors, for their enthusiasm.

To my editor, Liz Gorinsky.

Introduction

There have been many books written about Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland and its companion volume Through the Looking Glass and What Alice Found by Lewis Carroll, exploring their meaning—psychological, political, mathematical; and about their author, Charles L. Dodgson (1832–1898), a mathematician, logician, Anglican deacon, and photographer, and his relationship with the model for his heroine, Alice Liddell.

I’ve loved Carroll’s two classics since I was young. I wouldn’t say I’m obsessed, but I’ve been a collector of illustrated versions for many years, especially appreciating the enchanting illustrations of the books by fine artists such as Mervyn Peake, Arthur Rackham, Barry Moser, Ralph Steadman, Lisbeth Zwerger, Salvador Dali, Rodney Matthews, Anne Bachelier, Maggie Taylor, and so many others, some relatively unknown.

But I must admit that my vision of “Alice” herself has been subverted by the 1985 movie Dreamchild, in which the adult Alice Liddell, who is visiting New York, flashes back to her childhood. There we see the dark-haired little girl who inspired the tales as she was seen in photographs, very different from the long-haired blonde image created in John Tenniel’s ubiquitous illustrations. In that movie, which is very much about the relationship between Dodgson and Liddell and how his creation of her fictional counterpart might have influenced her life as an adult, there are darkly magical, partially animated interstitial sections with amazingly creepy Wonderland inhabitants imagined by Jim Henson. In fact, it might be the creatures in Carroll’s works that are even more likeable than Alice herself, bringing readers back over and over again to the land beyond the looking glass.

Everyone is familiar with Walt Disney’s 1951 animated musical version of Alice in Wonderland, which took about twenty years to get off the ground, and made an indelible mark on childs’ psyches with its colorful renderings of the Cheshire Cat, the Mad Hatter, the White Rabbit, the March Hare, the Hookah-smoking caterpillar, and one of my personal favorites: Dinah the kitten. In 1971, Czech filmmaker Jan Švankmajer made a short animated film based on the Jabberwocky, and in 1987 made a full-length feature, the darkly surreal Alice, which in its original language was called Something from Alice. Its tone was entirely different from the Disney. In 2010 and 2016, Director Tim Burton interpreted the two volumes in his own inimitable way. Love them or hate them, they did create a whole new set of images that one can savor. Then She Fell, a marvelous immersive performance piece created by the theater company Third Rail Projects, has played continuously in New York City since 2012. The ongoing popularity of all of these disparate visions demonstrates how strongly Carroll’s work continues to be loved.

So how did this anthology come about? I was being interviewed at a convention a few years ago, and someone from the audience asked me what anthology idea I hadn’t yet done but would like to. I mentioned that I adore the Alice books, and after the event, I was encouraged by several bar companions to try to sell such an anthology. So reader, I did. And this is what you now hold in your hands (or are reading on your screen): eighteen stories and poems inspired by Alice, by Lewis Carroll, by the critters of Wonderland. Some of the entries are fanciful, others are dark indeed. In either case, I hope you find as much enjoyment in these works as you have in the original books.

GENTLE ALICE

Kris Dikeman

MY OWN INVENTION

Delia Sherman

Two forward, one across, and I’m in a wood: the seventh square, since I know who I am. My horse is plodding down a path unspooling under her hooves like a ball of wool, only wider, while I think of ways to wake kings or small children or writers, all of whom seem to be constantly sleeping and dreaming of me in the seventh square on a horse with a mind of her own.

My horse’s name is Horse. She carries not only me, but also two sets of armor (hers and mine), a saddle, a spiked club, a sword, a mousetrap (sans mice), a bunch of carrots and another of onions, a beehive (sans bees), fire-irons, and a bundle of reeds for a campaign chair. It will fold and have its own sunshade and turn into a table, suitable for cards or tea. All I need is some string to tie it with. Or possibly glue. It’s my own invention.

In the clearing, the Red Knight is climbing onto his horse. Beside a large silver dish, suitable for serving plum-cake or sliding down a snowy hill, stands an Alice. The Red Knight brandishes his club and shouts at the Alice, who looks alarmed, as well she might. The Red Knight has a voice like cold pease porridge.

“Ahoy! Ahoy! Check!” I cry.

“She’s my prisoner, you know!” says the Red Knight crossly, and we fight. It is awkward and noisy and involves a great deal of Maneuvering and Mountaineering and things beginning with “T,” like Tumbling Topsy-Turvey and Tintinnabulation. I beguile the Tedium by Thinking of a way to make a ladder out of eels so that I may remount Horse without banging my shins on the fire-irons. After a while, the Red Knight and I simultaneously knock each other out of our saddles, and the move is over. We pick ourselves up, shake hands, and the Red Knight mounts and gallops off into the wood. I see the Alice standing behind a tree, wearing a curious expression compounded of apprehension, admiration, and amusement.

There is always an Alice in the seventh square. They are generally yellow-haired, with pinafores over blue dresses, striped stockings, and little black slippers. Male Alices are rare, as are whales and crickets and mice and any non-chess piece over the age of seven years and six months, give or take a decade.

This Alice’s hair is shorter than usual, and less golden.

“It was a glorious victory, wasn’t it?” I ask.

“It was not a victory, not really,” the Alice observes, brushing at her pinafore. “It was a draw. He just gave up and left.”

Here in Looking-Glass Land, everyone disagrees with one another more or less constantly—except for the Red King, because he is asleep, and me, because I can never be sure I’m not wrong.

“I’ll see you safe until the end of the wood,” I say soothingly. “And then you can be a queen.”

The Alice shrugs. “And it’s all feasting and fun. I know.” A sigh, not enraptured. “Come on. Let’s get it over with.”

We go through the business of getting my helmet off, I fasten it to Horse’s saddle, and we set off through the wood. It is getting on towards brillig, and I want to get the Alice disposed of quickly so I can have my tea. I have a fat borogove in my bag that should stew up very fine, with treacle.

Almost immediately, Horse snorts, stops short, and I tumble off her back into a ditch. The trees are like cobwebs against a glassy sky. Or perhaps the cobwebs are like trees. In my present position, it all comes to the same thing.

The Alice’s scowl comes between me and the cobwebs or trees. “You do that on purpose, don’t you?” she asks as she pulls me upright.

It occurs to me that this Alice, like a mouse on horseback, is not altogether comfortable with Looking-Glass ways. Perhaps she has tumbled into the wrong dream by mistake. “Do what?” I ask.

“Fall off your horse all the time. Nobody could be that clumsy.”

“Did you ever wonder,” I say mildly, “if a good cure for baldness might not be to coat your head in mud and plant grass?”

The scowl becomes a glare. “What’s with you, anyway? Do you have ADD?”

“Alice Daily Demands,” I say dreamily, climbing back up on Horse. “Articled Dozing Dormouse. Antique Doily Dolls. No, I don’t have any of those.”

One black-shod foot stamps dust from the path. “No! It’s a syndrome: Attention Deficit Disorder. It means you can’t pay attention in class.”

“I have been in a box and in a wood and in an order, child, but never in a class.”

The Alice makes a sound like an angry cat and marches away, leaving me to follow. When Horse and I catch up: “I don’t know why I’m dreaming about you,” the Alice grumbles. “This isn’t even my favorite book.”

I fall off again, into a ditch this time. To my surprise, the Alice pulls me out again. “Are you going to keep doing this? Because if you are, I think I’d rather go on by myself.”

“I was thinking, too!” I exclaim, “About names. There are all sorts, you know, just as there are all sorts of creatures. Take Humpty-Dumpty, for instance. His name means the kind of shape he is—”

“And a good, handsome shape it is, too,” the Alice murmurs.

“Just so. But the rest of us have to make do with names that say what kind of thing we are. The Sheep. The Red King. The Jabberwock. True,” I add thoughtfully, “there’s only one of each of them, so it’s not as confusing for them as it is for us Knights. Still, it’s not the same as having a real name.”

“Like Alice?”

The Alice’s tone is scornful, underscored with melancholy, and so far from the self-satisfied smugness I am accustomed to in Alices that I say, quite spontaneously, “Alice isn’t your name.”

Another scowl. “If it’s not, why am I wearing this stupid outfit?”

“Well, that’s it, you see. Here, Alice is what you do. If you flew, you would be a Gnat, or perhaps an Elephant. If you knitted, you’d be—”

“A Sheep,” the Alice interrupted. “That’s dumb. What you do isn’t what you are. I mean it is, in a way, but not like that.”

Disagreements, it seems, are like boats. Once you are in one, it is impossible to get out again without falling into deep waters. I sigh so deeply my armor rattles and my mustache flutters like eyelashes. “It certainly isn’t what I am. Perhaps that’s why I make such a bad one.”

We walk in silence for a space, and then the Alice says, “I feel you.”

I am about to ask for an explanation, or perhaps talk about mousetraps, when a furious outgribing breaks out in the distance.

The Alice whirls like a grig. “What’s that?”

“Too loud for a mome rath,” I say thoughtfully. “Unless there’s a herd, but it’s unlikely, this distance from a wabe.”

The outgribing gives way to whiffling. I unstrap my club. Though it might be large enough to give a Bandersnatch pause, it’s like hay for a headache against a Jabberwock. Still, it makes me feel better.

A wind sighs through the branches, wafting a stench of burned toast, and then the Jabberwock is upon us, burbling as it comes. It is clad in a scarlet cap with a little bill in front and a blousy white jacket, trimmed in scarlet and emblazoned with the mystical letters R-E-D-S-O-X.

The torpid mouth gapes, the lantern eyes goggle. I swing my club, miss, and fall off Horse from sheer momentum.

The Alice gives a little scream of absolute fury. “Get out, get out, get out! This is my dream!”

“Perhaps it’s a nightmare,” I offer from the prickle holly bush where I have landed.

“Joshjoshjoshjosh,” whiffles the Jabberwock.

The air fills with carrots, onions, and cabbages (alas for my borogove stew!), followed by the mousetrap, an ash-shovel, and a bellows. The Jabberwock burbles and roars, crashing its guillotine teeth, whirling its glaucous eyes. Huge clawed mitts clutch at the Alice, who has gained some inches of girth and height and is brandishing a vorpal blade that looks very like a fire-iron.

“Snicker-Snak! Snicker-Snak!” the Alice cries, and swings mightily.

The iron shears the whiskers from the Jabberwock’s chin as neatly as a razor and the monster rears back, tumbling along its long, scaly tail like a lizardly hoop, a look of blank astonishment on its fearsome countenance.

The Alice is nearly as tall as I, now, and considerably sturdier. The hair is shorter than ever and quite dark, the dress and pinafore transmogrified into blue pantaloons and a kind of buttonless shirt with short sleeves.

“Joshjoshjoshjosh,” burbles the Jabberwock.

“Go away,” shouts the child, who is most certainly not an Alice. “Or I’ll cut your head off and throw it to the crabs!”

The Jabberwock swells and gibbers. The not-Alice throws the vorpal fire-iron at it and it disappears like a bun at breakfast.

“That was too easy,” the not-Alice remarks, and extracts me from the bush.

“What were we talking about?” I ask.

“Names,” the not-Alice says. “You said mine wasn’t Alice.”

“Nor is it. Will you give me a leg up onto Horse? You seem to have thrown my stirrup at the Jabberwock.”

“Sorry.”

“Don’t mention it.”

Horse, unburdened of fire-irons and vegetables, is inclined to be frisky, but the not-Alice is now tall enough to steady me in the saddle. As we progress side by side, through the wood, I reflect how pleasant it is to ride without the trouble of falling off and clambering back up again. I regret the carrots, also the fire-irons and the stirrup. But the saddle is certainly more comfortable without the mousetrap.

The not-Alice flexes a strong arm and surveys it critically. “This isn’t right.”

“It is, you know,” I say apologetically. “Your right arm, that is.”

The not-Alice’s eyes roll briefly skywards. “Right. But it’s not my right arm.”

“Isn’t it attached?”

A sigh. “Yes, it’s attached, but that’s not what I mean. It’s the wrong arm; it’s not my arm!”

Horse stops short and lowers her head, expecting me to dive forward. When I do not, she looks reproachfully over her shoulder at the not-Alice holding me in the saddle, snorts, and walks on, ears at an offended angle.

“What kind of thing would you like to be?” I ask.

“Not sure,” the not-Alice says. “Not what my dad wants me to be, anyway.”

“And what’s that?”

“A real boy.”

For a moment, a boy walks at my stirrup. He is strong, like Horse, and his appearance hovers somewhere between Tweedledum and the Beamish Boy, with a touch of Bully and Bore about the eyes and mouth. Then the not-Alice returns, smaller and wispier than before, like a guttering candle.

“You could be an Alice if you like,” I say soothingly. “A real Alice.”

The not-Alice shrinks a little further. “No!”

“Without the pinafore?”

“The pinafore isn’t the point.”

Deep waters indeed, and not a boat in sight.

“You are sad,” I say. “Let me sing you a song to comfort you.”

“No way,” the not-Alice says.

“You haven’t heard the song yet,” I say, stung.

“I don’t need to. I’ve read it. It’s dumb. And kind

of pathetic and self-pitying.” The not-Alice stops, and so does Horse. I fall off.

The not-Alice watches as I get to my feet. “Josh.”

“I beg your pardon?”

The not-Alice is smaller now, and wispier than ever. “It’s my name. It’s short for Joshua, who was a mighty warrior. It’s a kind of joke, if you think about it, but it’s a pretty lame one.”

Smaller and smaller, less than Alice-sized, and shrinking. I cast around in my mind for something to say that will stop the process, but the best I can come up with is, “That’s not your name.”

“IT IS,” says a voice like an avalanche.

The sky is coming on very dark. The not-Alice-nor-Josh looks up and up at the giant bestriding the path. Or at least the giant’s foothills, which are covered with black-and-white shoes of no recognizable type, tied up with white rope, with two massive towers rising out of them into the clouds. The towers are pale, like dirty pinkish brick, and one of them is plastered with a shiny yellow banner decorated with what looks to be a giant bat.

“WEIRDO,” the avalanche adds.

The not-Alice-nor-Josh is sheep-sized now. In a moment, it becomes kitten-sized, then gnat-sized, then pawn-sized, after which I lose sight of it in the grass. I fear it has gone out altogether, like a candle.

“Quick,” I cry. “Who are you? Are you Jack? Are you Jill? Are you Beast? Are you Beauty? Tell me what you are!”

A pause, and then I hear a tiny squeak in the grass at my feet. The next moment, not-Alice-nor-Josh is visible, and visibly thinking hard. I know the look. I have felt it on my own face often enough, although my face is not as round, my mouth as determined, my eyes as dark, my hair as thickly bristling as the not-Alice-nor-Josh’s have grown.

The ground groans as the giant shifts its black-and-white shoes impatiently. “I’LL GRIND YOUR SOUL TO MAKE MY BREAD!” it thunders.

I unhook my club from Horse’s saddle and hold it in my arms, determined to do or die.

The not-Alice-nor-Josh looks at me, dark eyes glittering like poison, then cups two hands into a trumpet and shouts, “Hey! Giant-face! I have a riddle for you!”

Inferno

Inferno The Best of the Best Horror of the Year

The Best of the Best Horror of the Year When Things Get Dark

When Things Get Dark A Whisper of Blood

A Whisper of Blood Echoes

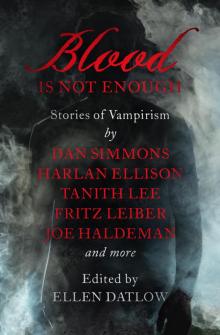

Echoes Blood Is Not Enough

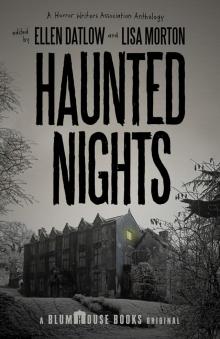

Blood Is Not Enough Haunted Nights

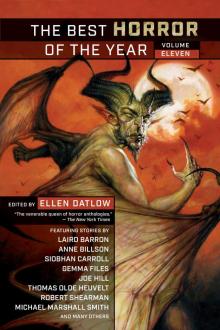

Haunted Nights The Best Horror of the Year Volume Eleven

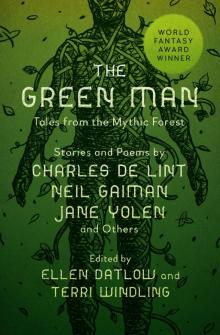

The Best Horror of the Year Volume Eleven The Green Man

The Green Man The Dark

The Dark Mad Hatters and March Hares

Mad Hatters and March Hares Nebula Awards Showcase 2009

Nebula Awards Showcase 2009 The Devil and the Deep

The Devil and the Deep