- Home

- Ellen Datlow

Inferno

Inferno Read online

I would like to dedicate this book to the memory of

CHARLES L. GRANT,

master storyteller, editor of the Shadows series,

and lovable curmudgeon (even when he was young).

We’ll never forget you.

1942–2006

Acknowledgments

I’d like to thank Gordon Van Gelder, who came up with the title several years ago at a dinner party. During the discussion of a good title for a non-theme horror anthology that I wanted to edit, he said, “How about ‘Datlow’s Inferno’?” We all laughed and I thought, how silly … yet when I actually wrote up the proposal, “Inferno” as a title didn’t seem so bad. And, of course, when anyone asks for it, I hope they’ll request “Datlow’s Inferno.”

I’d also like to thank my editor, James Frenkel, who fought hard to buy the book, and who has been supportive all along the way to the anthology’s completion.

Table of Contents

Title Page

Acknowledgments

Introduction by Ellen Datlow

Riding Bitch by K.W. Jeter

Misadventure by Stephen Gallagher

The Forest by Laird Barron

The Monsters of Heaven by Nathan Ballingrud

Inelastic Collisions by Elizabeth Bear

The Uninvited by Christopher Fowler

13 O’Clock by Mike O’Driscoll

Lives by John Grant

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

Ghorla by Mark Samuels

Face by Joyce Carol Oates

An Apiary of White Bees by Lee Thomas

The Keeper by P. D. Cacek

Bethany’s Wood by Paul Finch

The Ease with Which We Freed the Beast by Lucius Shepard

Hushabye by Simon Bestwick

Perhaps the Last by Conrad Williams

Stilled Life by Pat Cadigan

The Janus Tree by Glen Hirshberg

The Bedroom Light by Jeffrey Ford

The Suits at Auderlene by Terry Dowling

Copyright Acknowledgments

ALSO EDITED BY ELLEN DATLOW

Praise for Ellen Datlow’s - INFERNO

About the Editor

Notes

Copyright Page

Introduction

ELLEN DATLOW

I love the horror short story and novella. To me, they’re the most powerful and important forms in the field. For at least two hundred years the short form has proven to be enormously fertile ground for dark literature that plumbs the depths of fear and the evil that may reside in the human soul.

Undeniably, the novels of Stephen King and such other dark novels as The Monk by Matthew Gregory Lewis, Dracula by Bram Stoker, Frankenstein by Mary Shelley, as well as those by H. P. Lovecraft, have been enormously popular. Nonetheless, throughout the history of British and American horror, the short story has been the most celebrated form of the genre. Edgar Allan Poe, Nathaniel Hawthorne, M. R. James, Robert Bloch, Robert Aickman, Ray Bradbury, Shirley Jackson, Charles Beaumont, Richard Matheson, Ramsey Campbell, and Dennis Etchison, to name but a small number of great practitioners of the genre, are some of the authors who come to mind when we think of those who have crafted many of our favorite horror and terror tales.

I think that fiction of the supernatural works better in the shorter forms for the simple reason that the short form lends itself with great ease and flexibility to an enormous variety of narrative styles and strategies. Novels, while they can be quite chillingly effective, are an entirely different matter. Very few longer works truly carry the power to force the reader to sustain the suspension of disbelief necessary for the kind of stunning, chilling, or flat-out terrifying effect of a great short work.

Over the course of my career as an editor thus far, I have edited a number of anthologies that focus on stories with a common theme, the subjects ranging from sexual horror to cat horror stories; from stories of vengeance and revenge to ghost stories. I’ve enjoyed editing them all, but have always wanted to edit an all-original, non-themed horror anthology—to showcase the range of subjects imagined by a number of my favorite writers inside and outside the horror field.

The non-themed horror anthology is a rich part of the horror tradition: Series such as The Pan Book of Horror (taken over for several years by Gollancz and retitled Dark Terrors), edited by Stephen Jones and David Sutton; Shadows, edited by the late Charles L. Grant; Masques, edited by the late J. N. Williamson; and Borderlands, edited by Thomas F. Monteleone are all fine examples of series that have published outstanding original short fiction.

There have also been major one-shots of reprinted material such as The Playboy Book of Horror (an anthology that strongly influenced me as a reader and editor); The Arbor House Treasury of Horror and the Supernatural, edited by Bill Pronzini; Great Tales of Terror and the Supernatural, edited by Phyllis Wagner and Herbert Wise; The Dodd, Mead Gallery of Horror, edited by Charles L. Grant; Modern Masters of Horror, edited by Frank Coffey; The Dark Descent, edited by David G. Hartwell; and The Mammoth Book of Terror, edited by Stephen Jones. And the past thirty years have witnessed the publication of one-shot anthologies of original material. I think especially of the enormously successful Dark Forces, edited by Kirby McCauley; and others like The Cutting Edge and Metahorror, edited by Dennis Etchison; Prime Evil and Revelations, edited by Douglas E. Winter; and 999, edited by Al Sarrantonio.

When I’ve edited non-themed reprint anthologies (two OMNI series and twenty volumes of the horror half of The Year’s Best Fantasy and Horror), I’ve usually been surprised to discover that certain ideas or, if you will, themes recur anyway, and it’s not until the contents are chosen and I look at the stories as a group that the stories’ commonality reveals itself to me. However, the themes that I discover in those anthologies are the product of the work of authors writing for other editors, in a wide variety of venues ranging from slick magazines to semiprofessional ’zines, from single-author story collections to themed anthologies edited by any number of different editors.

In the present volume, though, I present for the first time stories all of which I’ve chosen and edited. And all of them had to succeed on my terms: to provide the reader with a frisson of shock, or a moment of dread so powerful it might cause the reader outright physical discomfort; or a sensation of fear so palpable that the reader feels impelled to turn up the lights very bright and play music or seek the company of others to dispel the fear; or to linger in the reader’s consciousness for a long, long time after the final word is read. Such stories are my passion. For fear is a part of life, and horrific or frightening stories have always been the surest way humanity has found to deal with the very tangible terrors of the real world. It’s been that way since people first sat around a fire, surrounded by the darkness and dangers of the wild beyond their circle of light. Listening to stories of the terrifying beasts and other natural threats, our ancestors used narratives to help conquer their fears, by putting them into tales that they themselves wrought, stories in which they dealt with fears by naming them, thus rendering them known, less powerful for being told, the stories handed down from generation to generation, a tool that has never lost its power and usefulness.

My editor at Tor Books, Jim Frenkel, told me, when we first discussed Inferno, that he still remembers with utter clarity the sensation of being terrified by a story he read when he was twelve years old. The details had blurred for him over the decades, but the actual feelings—of fear, of disquietude, of dread—remain vivid for him to this day. So vivid, in fact, that merely bringing up the subject caused him to experience immediately a flood of sensations which brought him a shiver that he couldn’t

suppress. I have memories like this as well as do, I know, many other people who enjoy horror.

But there are those who don’t read horror, short form or long, and there’s no arguing with personal tastes in reading, or anything else. Such people don’t seem to understand that being scared by the act of reading a work of fiction is not necessarily a trivial pursuit; at its best, it can be an act of catharsis. A cheap one, perhaps, but nonetheless quite real. When we are taken from the real world to a place only available through a story, we are free to be as frightened, as helpless as we can bear.

When the story is over and we emerge back in the real world, we’ve survived a test of courage, or of endurance, or whatever other tests the skilled author has posed to challenge us—or our imaginary avatar, as created within the narrative. And back in the real world, we are once again whole—and often, as readers have experienced in the most effective tales, we are more whole than before. A gifted storyteller’s craft can uplift, transform, and challenge us in ways that are either unlikely or downright impossible in the real world.

Vicarious adventures in terror are a lot easier to survive than some of the terrors we face in life. Violence, violation, loss, revulsion; mental, emotional, or physical suffering … all are trials that in life may bow us and break our spirit. In fiction, though, we survive them and are strengthened by our survival.

And that is the beauty of short horror. In its shorter lengths, horror fiction, as evidenced in an enormous number of effective, memorable works, continues to be a literary form that speaks to us powerfully. If one needs confirmation of this assertion, one needs look no further than film and television, which have been mining short fiction for almost a century. Television series such as The Twilight Zone, Alfred Hitchcock Presents, and others, as well as films too numerous to mention, have successfully adapted short horror fiction to the shivery delight of generations of viewers.

So here are twenty stories I hope you’ll enjoy. After editing as many books and magazines as I have, I’m not so naïve as to believe you’ll agree with every single story I’ve chosen. But if even one of these tales does for you what they have all done for me, perhaps you will have one of those great memories that will stay with you always, a memory of something dark, dangerous, and brooding. One that will bring you a momentary thrill when you recall it.

So … what have I discovered in putting together Inferno? Although there are no demonic children, there are missing children, abused and/or orphaned children who have experienced unspeakable horrors; angry adult children, children who inadvertently cause pain to their loved ones. The relationship between parent and child is primal and powerful, and its influence is lifelong.

In addition, you’ll find psychological and supernatural stories of madmen and -women; of the powerless and of those with too much power; tales of revenge and vengeance and loss.

To my mild surprise, I noticed there are no war stories here. Perhaps authors have realized that there is enough horror in the real wars we’ve been fighting for years. Nor are there zombies, vampires, witches (well, maybe one, if you stretch it), evil children, or werewolves. Their absence is not intentional, but I don’t think readers will be disappointed by the absence of these staples of horror fiction. There are plenty of other monsters within these pages.

I hope you’ll enjoy encountering them as I’ve enjoyed presenting them.

ELLEN DATLOW

New York City

November 2006

Riding Bitch

K. W. JETER

K. W. Jeter has written some very edgy novels, including Dr. Adder, The Glass Hammer, and Infernal Devices. He has also had a number of short stories published. His work defies classification.

A lot was still going to happen.

A He would stand at the bar, he knew, locked in the embrace of his old girlfriend.

“Probably wasn’t your smartest move.” Ernie the bartender would run his damp rag along the wood, polished smooth by the elbows of generations of losers. “Sounds like fun at the beginning, but it always ends in tears. Trust me, I know.”

He wouldn’t care whether Ernie knew or not. The beer wouldn’t do anything to numb the pain. Not the pain of having a dead girl, whom once he’d loved, draped across his shoulders. Her left arm would circle under his left arm. When she’d been alive, whenever she’d conked out after too many Jäger’s and everything else, she’d always wrapped herself around him just like that, from the back. Up on tiptoes in her partying boots, just blurrily awake enough to clasp her hands over his heart.

He would knock back the rest of the beer in front of him, remembering how he’d carried her, plenty of nights, when there’d still been partying left in him. He’d shot racks of pool like this, leaning over the cue with her negligible weight curled on top of his spine like a drowsy cat, her face dropping close beside his, exhaling alcohol as he took his shot, skimming past the eight ball … .

Her breath wouldn’t smell of anything other than the formaldehyde or whatever it was that Edwin had pumped her full of, back at the funeral parlor. And it wouldn’t really be her breath, anyway, her not having any in that condition. He would gaze at the flickering Oly Gold neon in the bar’s bunker-like window, and swish another pull of beer around in his mouth, as though it could Listerine away the faint smell in his nostrils. The dead didn’t sweat, he would discover, but just exuded—if you got that close to them—an odor half the stuff hospital floors were mopped with, half Barbie-doll plastic.

“Those look like they chafe.”

Ernie the bartender would catch him tugging at the handcuffs, right where the sharp edge of metal would be digging through his t-shirt and into the skin over his ribs.

“Yeah,” he’d say, “they do a bit.” Should’ve thought of that before you let ’em strap her on. “I wasn’t thinking too clearly then.”

“Hm?” Ernie wouldn’t look over at him, but would go on peering into the beer mug he’d just wiped with the bar towel.

“I blame it on Hallowe’en,” he would explain.

“Hallowe’en, huh?” Ernie would glance at the Hamm’s clock over the bar’s entrance. “That was over three hours ago.” Ernie would lick a thumb and use it to smear out a grease spot inside the mug. “Over and done with, pal.”

“Couldn’t prove it around here.” The bar would be all orange-’n’-blacked out with the crap that the beer distributors unloaded every year: cheap cardboard stand-ups of long-legged witches with squeezed cleavage, grinning drunk pumpkins Scotch-taped to the wall over by the men’s room, bar coasters with black cats arched like croquet wickets, Day-Glo spiderwebs, dancing articulated skeletons with hollow eyes that would’ve lit up if the batteries hadn’t already run flat by the thirtieth, everything with logos and trademarks and brand names.

“Why do you let them put all that up, Ernie?”

“All what up?” The bartender would start on another mug, scraping away a half-moon of lipstick with his thumbnail. “What’re you talking about?”

He’d give up then. There’d be no point. What difference would it make? He’d shift the dead girl a little higher on his shoulder, balancing her against the tidal pull of the beers he would put away. The combination of low-percentage alcohol with whatever the EMTs would huff him up with, when they scraped him off the road and into their van, would wobble his knees. Hanging onto the edge of the bar, instead of trying to walk, might be the only good idea he’d have that night.

And not all the ideas, the weird ones, would be his. There would still be that whole trip the other guys in the bar would come up with, about the reason Superman flies in circles.

But everything else—that would still be Hallowe’en’s fault. Or what Hallowe’en had become. That was what he had told the motorheads, back when the night had started.

No—Cold lips would nuzzle his ear. You’ve got it all wrong.

He’d close his eyes and listen to her whisper.

It’s what you became. What we became. That’s what did it.

<

br /> “Yeah …” He’d whisper to himself, and to her as well, so no one else could hear. “You’re right.”

“I blame it all on Hallowe’en.”

“That so?” The motorhead with the buzz cut didn’t even look up from the skinny little sport bike’s exhaust. “What’s Hallowe’en got to do with your sorry-ass life?”

He hadn’t wanted to tell someone else exactly what. He hadn’t wanted to tell himself, to step through the precise calculus of regret, even though he already knew the final sum.

“It’s not me, specifically,” he lied. “It’s what it did to everything else. It’s frickin’ satanic.”

That remark drew a worried glance from Buzz Cut. “Uhh … you’re not one of those hyper-Christian types, are you?” He fitted a metric wrench onto a frame bolt. “This isn’t going to be some big rant, is it? If it is, I gotta go get another beer.”

“Don’t worry.” Something he’d thought about for a long time, and he still couldn’t say what it was. Like humping some humongous antique chest of drawers out through a doorway too small for it, and getting it stuck halfway. He could wrestle it around into some different position, with the knobs wedged against the left side of the doorjamb rather than the right, but it would still be stuck there. “It’s just …”

“Just what?”

He tried. “You remember how it was when you were a kid?”

“Vaguely.” Buzz Cut shrugged. “Been a while.”

“Regardless. But when we were kids, Hallowe’en was, you know, for kids. And the kids got dressed up, like little ghosts and witches and stuff. The adults didn’t get all tarted up. They stayed home and handed out the candy.”

“True. So?”

“So you’ve got three hundred and sixty-four other days, including Christmas, to act like a cheap bimbo, or to prove that you’re a beer-soaked trashbag. Why screw around with Hallowe’en?”

Inferno

Inferno The Best of the Best Horror of the Year

The Best of the Best Horror of the Year When Things Get Dark

When Things Get Dark A Whisper of Blood

A Whisper of Blood Echoes

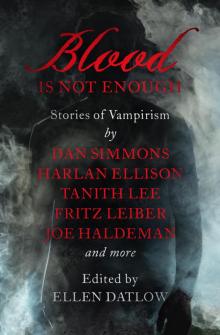

Echoes Blood Is Not Enough

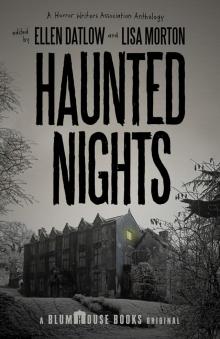

Blood Is Not Enough Haunted Nights

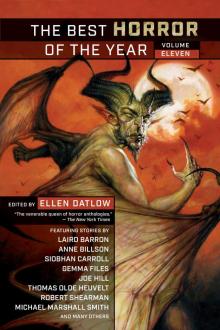

Haunted Nights The Best Horror of the Year Volume Eleven

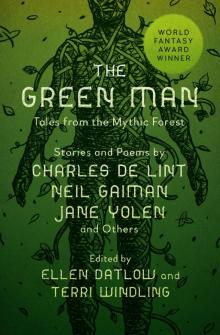

The Best Horror of the Year Volume Eleven The Green Man

The Green Man The Dark

The Dark Mad Hatters and March Hares

Mad Hatters and March Hares Nebula Awards Showcase 2009

Nebula Awards Showcase 2009 The Devil and the Deep

The Devil and the Deep