- Home

- Ellen Datlow

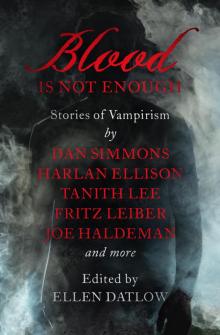

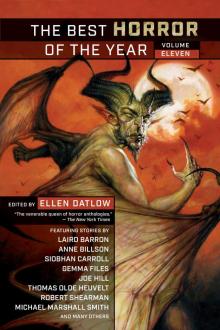

The Best Horror of the Year Volume Eleven Page 10

The Best Horror of the Year Volume Eleven Read online

Page 10

“You just mean he’s a dick but I’ll get used to it.”

I’d laughed. You knew a bit about people and how to put up with them, I suppose. Seemed that way, on Big Brother I mean, but that might just have been the way it was presented. That’s the thing with TV stuff. It’s all about the editing.

Tennyson once wrote that nature was “red in tooth and claw,” and it’s true. I’ve seen it. In Africa alone I’ve seen a baby giraffe pulled to pieces by a pack of hyenas, a wildebeest split apart in a crocodile tug of war, and an elephant brought down by a pack of hungry lions. I know it’s supposed to be a pride of lions but when you’re sitting in the middle of it, “pack” feels far more appropriate. Pride suggests a nobility that just isn’t there. It’s hard to see a lion as the king of beasts when his mane is matted with blood where he can’t lick it clean. If he’s a king, he’s a savage one.

Following that group of zebra, we were actually hoping for some of that tooth and claw. We’d filmed them interacting, of course, their feeding habits, social activity, but really we were waiting for something else. They’re beautiful creatures, zebra. Serene. Born to be on the screen, it seems, but doomed to be prey. That’s what we were waiting for.

And that was what we got.

You were the first to notice it happening. “They’ve seen something,” you said. “Or maybe they’ve heard something.”

You were right.

Eddie pointed. “Look.”

“Beautiful,” said Tony.

In the grass, rising from the dusty ground, was a motley mix of colour. Orange, red, brown, and black, all of it blending together in dirty patches. Spots of colour like rusty stains.

“And there. Look.”

“How many’s that? Ten? Twelve?”

African hunting dogs. Wild dogs. Lycaon pictus, or “painted wolf.” A formidable group of them, too. They’re small, but what they lack in strength they more than make up for in numbers.

By the time we had the cameras on them they were trotting towards the herd of zebras at a steady six, maybe seven miles per hour.

“They’re picking up the pace,” I said.

The herd saw them and fled.

“Look, look, there they go!” You checked to see which of the cameras was on you and turned back to face the action. I had the boom pole overhead, ready for whatever you might say.

“They’ve singled one out.”

The African hunting dog is a pack hunter. With agile prey like gazelles or impala, they have to be, flankers cutting off escape routes and narrowing the choices of their prey. With the zebra, though, it’s a straight chase.

“Look at them go!”

The pack focused their attention on one of the young females. When the first of the dogs leapt, you startled me with a sharp gasp. The dog tore into the zebra as it landed, dragging its claws across the animal’s hide as it slid back down over the rump. The zebra kicked it away with a rear hoof, but the dog re-joined the chase as a new lead attacked, leaping to grab hold of the zebra’s muzzle. It sank its teeth into the soft sensitive flesh of the zebra’s mouth and clawed at the face. With its head forced down, the zebra slowed enough that the other dogs could attack its hind legs, clawing at the muscle, piling onto its back. They tumbled together in a cloud of dust and a high cry of pain from the zebra. There was a mad scrabbling as the zebra tried to stand, dogs tearing at its flesh, but it was too late. It had been too late from the moment it hit the ground. One of the dogs got hold of an ear, more by accident than design, and tore it free. Worse than this, though, the soft flesh of the zebra’s underbelly was exposed. We watched as the animal was disembowelled alive, the pack clawing out its insides as the poor beast kicked for all it had left. One of the dogs burrowed its way into the stomach. Two others yanked at the legs, making a wide V of them until eventually one was torn free from the body. And still the zebra struggled, writhing and rolling as best it could beneath a mass of dirt-furred bodies. I was relieved when one of them finally clutched the zebra’s throat closed in its mouth and yanked the animal dead.

We actually celebrated, do you remember? Eddie, Tony, you, me: we all gave muted congratulations, hissed a quiet “yes!” of success and high-fived like we’d played a part in the spectacle ourselves. I guess we had, in a way: we’d watched and done nothing. Nothing but film it, anyway. But the African hunting dog, the wild dog, is one of the world’s most efficient and elusive predators and we had caught the entire thing on film. It was amazing, something to put us with the heavy hitters. Shit, even Planet Earth hadn’t caught a wild dog kill on camera. It was just luck, really. Ours, not the zebra’s. We’d been in the right place at the right time, that was all. It would’ve happened whether we’d been there to see it or not.

Although we’d been quiet with our congratulations, something aroused the attention of the dogs. Maybe the wind changed. They looked over at us, a dozen or so all at once. It was eerie, that shared reaction. They didn’t run, not with a fresh kill, but they watched us as we watched them. One of them held the zebra’s severed tail limp in its mouth. It was a great shot.

Nature, red in tooth and claw. Caught on film.

“But the African hunting dog is also a very social animal . . .”

My words, your voice, right to the camera as we filmed follow-up footage. With some animals the violence didn’t necessarily end after the main event—there could be fighting over the carcass—but the dogs, they shared their spoils equally. Even a latecomer who had missed the hunt was provided for.

The remaining zebra stood grazing, not very far away at all. They could probably see what the dogs were doing if they looked but they kept their heads down, safe for the time being as the dogs ate and played and napped.

“Let’s do that again without the but,” Eddie said, covering other editing choices; the kill may have been the first thing we filmed but it wouldn’t necessarily be the first thing you saw by the time it hit the screen.

“Why, what’s wrong with my butt?”

You turned your back to the camera and bumped your behind left and right, shimmying it down in a provocative wiggle. This was the Jenny we knew from Big Brother. A little bit of Z-list celebrity, shining through, wanting to be a star.

“Fuck’s sake, Jenny.”

Tony had only been filming for a few minutes, but he was already getting irritable. A few minutes feels a lot longer when you’re lugging camera equipment around under an African sun. I was feeling the same strain. I had the sound mixer in my shoulder satchel, cans clamped over my ears, and the boom pole raised so that the armpits of my shirt were exposed for all to see just how much I was feeling the heat.

You did that thing where you wipe a hand down over your face, straightening your expression into something more serious. “Emotional reset,” you called it. Or Davina did. Someone.

“The African hunting dog is a very social animal . . .”

Occasionally, as you spoke, one of the dogs would raise its head from where it dozed with the pack or look back from where it stood panting in the dry air. Did you feel them watching? I did. I can still feel them, even now. All the way down here. Their breath is hot on my skin.

It happens to everyone at some point, I’m told. This connection between man and animal. A friend of mine once saw an elephant brought down by lions in the dead of night. He watched the whole thing unfold in green-tinged light on a night monitor and it stayed with him forever after. Elephants bleat, did you know that? My friend used to hear that sound in the dark whenever he tried to sleep, an elephant’s bleating struggle as a tawny carpet of lions writhed on its body. Someone else I’d known a few years ago saw a Komodo dragon bite a buffalo then stalk it for days until the poison claimed it. You’re not supposed to interfere in this job. You just let it happen and record it, impartial, as nature runs its course. But it gets to you sometimes. I mean, how natural is it to watch something suffer and do nothing?

Not that there’s anything I could have done. Not about the dogs. Not about

any of it.

“. . . prowling for prey in highly organised units, or simply relaxing together, howling in play.”

I liked the rhyme of that. It chimed well. Prowling and howling. Prey and play.

“Good,” said Eddie. “Now the other way around.”

You turned your back to the camera again—“Like this?”—and began reciting the same lines. I don’t know if you were joking or not but Tony made no attempt to hide his frustration either way. “Christ, Jenny, stop pissing about.”

The narration felt clunky second time.

“Okay, cut there,” said Eddie.

I brought my arms down with relief and you stepped away from the descending microphone, exaggerating your dodge and ducking dramatically with a cry of, “Watch it!”

The dogs skittered. They didn’t move far, but they were suddenly alert and looking our way.

Nobody said anything. Your smile disappeared without needing an emotional re-set.

We waited.

Slowly, one by one, the dogs began to leave. They took as much of what was left of the carcass as they could carry.

“Shit.”

“Film me,” you said, motioning us all at you with beckoning hands, “film me, film me.”

“Jenny—”

But Eddie had his camera up and so Tony followed suit. Eddie said, “The dogs,” and Tony turned to film them walking away.

“The pack moves in single file, the alpha male leading, but for much of the day they will sleep the heat away in the shade . . .”

And so on, as you improvised a way for us to edit the footage together. Eddie encouraged you with quick hand-rolling gestures and I tried to think some script your way. You even shifted your position, squatting down in the dirt so the shot could look like a separate occasion, gesturing behind as if the dogs were still sitting somewhere nearby. It was good.

“In Kruger National Park, there is a predator easily identified by the blotchy colours of its coat. Shades of orange, brown, and black, with a long tail tipped in white, this is the ‘painted wolf,’ better known as the African hunting dog . . .”

I kept glancing at them. The heat rising from the ground turned them into wavy shapes, phantoms, and before long they were gone altogether.

“You okay, Tom? Want some water?”

You tried to pass me your own bottle but I had little chance to take it, grabbing wildly at the side of the truck instead as we bounced high and came down hard. We always sat in the back with the equipment, you and me, because we were the smallest. Even as cramped as it was we spent a lot of our travel time up in the air and then slamming our behinds. We got banged around a lot making sure the equipment didn’t.

“Woah! That was a good one. Here.”

I took the water, more because you’d offered than because I was thirsty.

“Do you think we got enough back there?”

You were worried you’d screwed up.

“We got enough,” I said. “We’ll probably only use three minutes or so.”

“Really?”

“Yeah. Probably just the kill, and a little bit of what came after. Lucky we were running behind schedule or we might have missed it.”

You smiled, and said, “Everything happens for a reason.”

“Yeah. I suppose it does.”

Eddie slowed the truck. I looked around in case he’d spotted something and I thought maybe—“What’s going on?” You had to shout to Eddie over the sound of the engine.

“Dogs,” I said.

But after a quick look you shook your head.

I couldn’t see them either. The sky was taking on a darker hue. The sun was going down, a trick of its light and heat making one end seem squashed as it slipped below the horizon. Shadows were growing long and dark around us.

“Looking for a camp spot,” Eddie yelled back.

“But the caves are so close. We might as well keep going.”

“Not in the dark.”

“You’ve driven at night before.”

“Yeah, but it’s rockier now, and I don’t really want to be fixing a tyre again, not out here. Not at night.”

We were already on our last very-patched spare, and the early hours of evening increased the risk of puncture, maybe worse, thanks to the poor visibility.

“But it’s okay to camp here at night?”

You had a good point. “I’m sleeping in the truck,” I said.

“I’m done with sleeping in the fucking truck,” Eddie said.

And of course, Tony supported that. “Nothing to be scared of here,” he said, “There’s nothing but us.”

“Well, I think I’ll join Tom in the truck.” You smiled. “If that’s okay with you?”

As if it wouldn’t be.

In the early days of the shoot, sleeping had been difficult. Do you remember? We’d been following those lions, sleeping whenever they did, which often meant during the day, which always meant we were hot and sweating and attracting flies and not actually sleeping much at all. In the open bed of the truck there wasn’t much protection against the incessant buzzing of flies or their frequent landings. Not much protection against lions, either, for that matter, though they turned out to be rather dull. Placid. Did you ever play that game, sleeping lions? We used to play it at school. You had to lay down and pretend to sleep while someone else played hunter, moving among the sleeping lions and trying to get them to move. You weren’t supposed to touch them but you could get close and whisper, say things to make them stir. Of course, we couldn’t do that, not with real lions. We took turns napping at night, but following lions over the rise and fall of Africa made that nearly impossible and even when we were able to stop driving for a while the lions growled constantly. A low, throaty sound. Engines in muscled flesh. All of it made everybody tired and irritable. A bit tense, as well.

It was like that the night after the dogs, too. Unpacking the truck, setting up camp, I could feel a building growl, and little irritations flitted around like flies.

“If only we had a heli-gimble,” Tony said, looking back the way we’d come. Thinking of the dogs, probably. “If only you’d stop saying that.”

That got you the middle finger without him so much as glancing around. From me, a smile, but I doubt you noticed.

“If only we had a helicopter to mount the heli-gimble on, eh?”

That was the best I could do.

Tony was right though; it would have been a great bit of kit to have. Three-sixty-degree filming, good long shots, good close-ups from even a kilometre away . . . but bloody expensive, and we were still low budget. None of this “three years in the making” with us. No slow motion predator action or time-lapse prey decay.

I was setting up a light in the back of the truck, along with a monitor and one of the cameras we did have. I wanted to check the infrared for when we were in the caves. I wanted to distract myself.

“You all right, Tom?”

“Hmm? Yeah, I’m fine. Just, you know . . .” I held up a memory card, titled and dated, adding the details to the index in my notebook. If I didn’t do it, nobody would.

Eddie glanced at us. “He’s not fine,” he said. “That kill got to him. What’s wrong, mate? Tooth and claw and all that shit, remember?”

That annoyed me. Partly because he was right, it had bothered me, but also because until that moment the distraction had been working just fine.

“You’re either spots or stripes in this world. Dog or a zebra. Sad, but true.”

“I’m fine,” I said again. “Looking forward to the caves.”

That was a lie, but I thought it would change the subject because Eddie was looking forward to them. Much of his campfire talk had been of his hikes and climbs in the Australian Blue Mountains. Sorry, the “Blueys.” Not really mountains but a plateau eroded into mountainous shape. Anyway, it worked, although he quickly turned the conversation around to one of his ’Nam stories, climbing around the caves of the Annamite Mountains. He’d also explored some o

f the Hang Son Doong in Phong Nha-Ke Bang which was supposed to be our next stop after Africa. The Hang Son Doong, or “mountain river cave,” is the biggest cave passage ever measured. The Echo Caves, though, are some of the oldest caves in the world. They haven’t been fully measured yet, and we had special permission to explore further than any of the offered tours.

“You really staying in the truck?” Tony asked. I was spreading my sleeping bag out on the floor near the monitors. I shrugged.

You tossed your bag to me as well.

“Let us warn you about Tom, love,” Eddie said, but that was all I heard. I looked up to see him making a tiny hook with his little finger. Tony laughed. “Never had any complaints,” I said.

You gave me your most dazzling smile yet, said, “Tom, you sly dog,” and I remember thinking this is what I need to be like? This is how I get you to notice me?

“Friend of mine did this cave a few years back,” Eddie told us. “For Planet Earth, I think. Gomantong. You guys see it?”

I knew the episode and nodded with Tony.

“Yeah,” Eddie said. “Gomantong.” He smiled at me. “That was full of shit, too.”

Tony roared with laughter.

“No offence, mate,” Eddie said.

I ignored Eddie to look at you. You gave us all a sort of half-smile. “I don’t get it.”

“Gomantong cave,” Eddie explained. “It’s—”

“A shithole.”

Stealing his pun was the best I could do for retaliation. He scowled at me but recovered quickly.

“Yeah. It’s a shithole. A cave literally full of shit. Guano. Friend of mine, Scud, good fella, he said that pile of bat crap was a hundred metres high and swarming with all sorts of things. Cockroaches, centipedes, crabs. All sorts of creatures. They never even had to leave the cave. That steaming pile had its own fucking—what do you call it?—ecosystem.”

“You ever get crabs from a dirty hole, Eddie?”

I don’t think you were sticking up for me. You were trying to get involved in the conversation. The new girl still trying to fit in. We’d talked about it before and you’d compared it to that Big Brother house, how it took the group a while to accept anyone new. It’s the same with animals, although with animals it can be even more brutal.

Inferno

Inferno The Best of the Best Horror of the Year

The Best of the Best Horror of the Year When Things Get Dark

When Things Get Dark A Whisper of Blood

A Whisper of Blood Echoes

Echoes Blood Is Not Enough

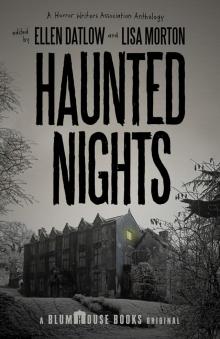

Blood Is Not Enough Haunted Nights

Haunted Nights The Best Horror of the Year Volume Eleven

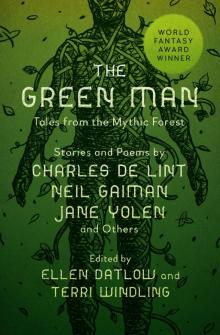

The Best Horror of the Year Volume Eleven The Green Man

The Green Man The Dark

The Dark Mad Hatters and March Hares

Mad Hatters and March Hares Nebula Awards Showcase 2009

Nebula Awards Showcase 2009 The Devil and the Deep

The Devil and the Deep