- Home

- Ellen Datlow

Inferno Page 14

Inferno Read online

Page 14

But nothing affected the Hollywood elite; they hung on, flirting with subversion when really, what they wanted to make was musicals. They still threw parties, though, and the next one was a killer.

This was the real deal, a ritzy Beverly Hills bash with a sizeable chunk of the A-list present, thrown in order to promote yet another Planet of the Apes movie. The sequels were losing audiences, so one of the executive producers pulled out the stops and opened up his mansion—I say his, but I think it had been built for Louise Brooks—to Hollywood royalty. This time there were security guards manning the door, checking names against clipboards, questioning everyone except the people who expected to be recognized. Certainly I remember seeing Chuck Heston there, although he didn’t look very happy about it, didn’t drink, and didn’t stay long. The beautiful girls had turned out in force, clad in brilliantly jeweled mini-dresses and skimpy tops, slyly scoping the room for producers, directors, anyone who could move them up a career notch. A bunch of heavyweight studio boys were playing pool in the smoke-blue den while their women sat sipping daiquiris and dishing dirt. The talent agents never brought their wives along for fear of becoming exposed. I’d been invited by a hot little lady called Cheyenne who had landed a part in the movie purely because she could ride a horse, although I figured she’d probably ridden the producer.

So there we were, stranded in this icing-pink stucco villa with matching crescent staircases, dingy brown wall tapestries, and wrought-iron chandeliers. I took Cheyenne’s arm and we headed for the garden, where we chugged sea breezes on a lawn like a carpet of emerald needles. Nearby, a fake-British band played soft rock in a striped marquee filled with bronze statues and Santa Fe rugs. I was looking for a place to put down my drink when I saw the same uninvited group coming down from the house, and immediately a warning bell started to ring in my head.

It was a warm night in March, and most people were in the torch-lit garden. The Uninvited—that’s how I had come to think of them—helped themselves to cocktails and headed to the crowded lawn, and we followed.

“See those people over there?” I said to Cheyenne. “You ever see them before?”

She had to find her glasses and sneak them on, then shook her glossy black hair at me. “The square-jawed guy on the left looks like an actor. I think I’ve seen him in something. The girls don’t seem like they belong here.”

“What it is, I’m beginning to think there’s some really harmful karma around them.” I told her about the two earlier parties.

“That’s nuts.” She laughed. “You think they could just go around picking fights and nobody would notice?”

“People here don’t notice much, they’re too busy promoting themselves. Besides, I don’t think it’s about picking fights, more like bringing down a bad atmosphere. I don’t know. Let’s get a little closer.”

We sidled alongside one of the men, who was whispering something to the shorter, younger of the two girls. He was handsome in a dissipated way, she had small feral features, and I tried figuring them first as a couple, then part of a group, but couldn’t get a handle on it. The actor guy was dressed in an expensive blue Rodeo Drive suit, the other was an urban cowboy. The short girl was wearing the kind of cheap cotton sunflower shift they marked down at FedCo, but her taller girlfriend had gold medallions around her throat that must have cost plenty.

Now that I noticed, they were all wearing chains or medallions, The cowboy guy had a ponytail folded neatly beneath his shirt collar, like he was hiding it. Something about them had really begun to bother me, and I couldn’t place the problem until I noticed their eyes. It was the one thing they all had in common, a shared stillness. Their unreflecting pupils watched without moving, and stayed cold as space even when they laughed. Everyone else was milling slowly around, working the party, except these four, who were watching and waiting for something to happen.

“You’re telling me you really don’t see anything strange about them?” I asked.

“Why, what do you think you see?”

“I don’t know. I think maybe they come to these parties late, uninvited. I think they hate the people here.”

“Well, I’m not that crazy about our hosts, either,” she said. “We’re here because we have to be.”

“But they’re not. They just stand around, and cause bad things to happen before moving on,” I told Cheyenne. “I don’t know how or why, they just do.”

“Do you know how stoned that sounds?” she hissed back at me. “If they weren’t invited, how did they get through security?” She reached on tiptoe and looked into my eyes. “Just as I thought, black baseballs. Smoking dope is making you paranoid. Couldn’t you just try to enjoy yourself?”

So that’s what I did, but I couldn’t stop thinking about the guest dying in the pool, and the guy who had fallen down the stairs. We stayed around for a couple more hours, and were thinking about going, when we found ourselves back with the Uninvited. A crowd had gathered on the deck and were dancing wildly, but there they were, the four of them, dressed so differently I couldn’t imagine they were friends, still sizing things up, still whispering to each other.

“Just indulge me this one time, okay?” I told Cheyenne. “Check them out, see if you can see anything weird about them.”

She sighed and turned me around so that she could peer over my shoulder. “Well, the square-jawed guy is wearing something around his neck. Actually, they all are. I’ve seen his medallion before, kind of a double-headed axe? It means God Have Mercy. There are silver beads on either side of it, take a look. Can you see how many there are?”

I checked him out. The dude was so deep in conversation with the short girl that he didn’t notice me. “There are six on each side. No, wait—seven and six. Does that mean something?”

“Sure, coupled with the double axe, it represents rebellion via the thirteen steps of depravity, ultimately leading to the new world order, the Novus Ordor Seclorum. It’s a satanic symbol. My brother told me all about this stuff. He read a lot about witchcraft for a while, thought he could influence the outcome of events, but then my mother made him get a job.” She pointed discreetly. “The girl he’s talking to is wearing an ankh, the silver cross with the loop on top? It’s the Egyptian symbol for sexual union. They’re pretty common, you get them in most head shops. Oh, wait a minute.” She craned over my shoulder, trying to see. “The other couple? She’s wearing a gold squiggle, like a sideways eight with three lines above it. That’s something to do with alchemy, the sign for black mercury maybe. But the guy, the cowboy, he’s wearing the most potent icon. Check it out.”

I looked, and saw a small golden five lying on his bare tanned chest. Except it wasn’t a five; there was a crossed line above it. “What is that?”

“The Cross of Confusion, the symbol of Saturn. Also known as the Greater Malefic, the Bringer of Sorrows. Saturn takes twenty-nine years to orbit the sun, and as a human life can be measured as just two or three orbits, it’s mostly associated with the grim reaper’s collection of the human soul, the acknowledgment that we have a fixed time before we die, the orbit of life. However, we can alter that orbit, cut a life short in other words. It’s a satanic death symbol, very powerful.”

I got a weird feeling then, a prickle that started on the back of my neck and crept down my arms. I was still staring at the cowboy when he looked up and locked eyes with me, and I saw the roaring, infinite emptiness inside him. I never thought I was susceptible to this kind of stuff, but suddenly, in that one look, I was converted.

We were still locked into each other when Cheyenne nudged me hard. “Quit staring at him, do you want to cause trouble?”

“No,” I told her, “but there’s something going down here, can’t you feel it? Something really scary.”

“Maybe they just don’t like black dudes, Julius. Or maybe they’re aliens. I really think we should go.”

Just then, the Uninvited turned as one and walked slowly to the other side of the dancing crowd until I could

no longer see them properly. A few moments later I heard the fight start, two raised male voices. I’d been half expecting it to happen, but when it did the shock still caught me.

He was in his late fifties, balding but shaggy-haired, dressed in a yellow KEEP ON TRUCKIN’ T-shirt designed for someone a third his age. I saw him throw a drink and swing a fat arm, fist clenched, missing by a mile. Maybe he was pushed, maybe not, but I saw him lose his balance and go over onto the table as if the whole thing was being filmed in slow motion. The kidney-shaped sheet of glass that exploded and split into three sections beneath him sliced through his T-shirt as neatly as a scalpel, and everyone jumped back. God forbid the guests might ruin their shoes on shards of glass.

He was lying as helpless as a baby, unable to rise. A couple of girls squealed in revulsion. When he tried to lift himself onto his elbows, a wide, dark line blossomed through the cut T-shirt. He flopped and squirmed, calling for help as petals of blood spread across his shirt. The music died and I heard his boot heels hammering on the floor, then the retreating crowd obscured my view. Nobody had rushed to his aid; they looked like they were waiting for the Mexican maids to appear and draw a discreet cloth over the scene so that they could return to partying.

Why didn’t I help? I have no answer to that question. Maybe I was more like the others back then, afraid of being the first to break out of the line. I feel differently now.

Cheyenne was pulling at my sleeve, trying to get me to leave, but I was looking for the Uninvited. If they were still there, I couldn’t see them. They’d brought misfortune to the gathering once more and disappeared into the despairing confusion of the Los Angeles night.

As I had twice before, I found myself searching the papers next morning for mention of the drama, but any potential scandal had been hastily hushed up. I lost touch with Cheyenne for a while, even began to think I’d imagined the whole thing, because the next month my career took off and I stopped smoking dope. I’d landed the lead role in a new movie about a street-smart black P.I. called Dynamite Jones, and I needed to keep my head straight, because the night schedule was punishing and I couldn’t afford to screw up.

We wrapped the picture in record time, without any serious hitches, although my white love interest was replaced with a black girl two days in, and our big love scene was cut to make sure we didn’t upset the heartland audiences. Perry Sapirstein held the wrap party at his house on Mulholland because they were striking the set and we couldn’t keep the studio space. I figured it was a good time to hook up with Cheyenne again—she’d been in Chicago appearing in an antiwar show that had tanked, and wanted to get a little more serious with me while she was waiting for another break out West.

I thought I’d know everyone there, but there were still some unfamiliar faces, and of course, the Beautiful Girls were out in full force, hoping to get picked for something, anything before their innocence faded and their faces hardened. The Hollywood parties were losing their appeal as I got used to them. I could see the establishment would never be unseated from their grand haciendas. They flirted with rebellion but would revert to type at the first opportunity, and everyone knew it.

I’d forgotten all about the Uninvited. People were caught up in the events unfolding in Vietnam, and fresh stories of atrocities on both sides were being substantiated by shocking press footage that brought the war to everyone’s doorstep. I didn’t meet anyone, ever, who thought we should be there, but I was in liberal California, and it would take some time yet for the mood to sink in across the nation. The sense of confusion was palpable; hippies were hated and feared wherever they went, and the young were viewed with such suspicion beyond the Democrat enclaves that it felt dangerous to step over state lines. Folks are frightened of difference and change, always were, always will be, but back then there were no guidelines, no safety barriers. There was no one to tell us what was right, beyond what we felt in our hearts.

We couldn’t see how far we were blundering into darkness.

Even in the strangest times, somebody will always continue to throw a party and act like there’s nothing wrong. So it was on Mulholland, where the gold tequila fountains filled pyramids of sparkling salt-rimmed glasses, and invisible waiters slipped between the guests with shrimps arranged on pearlized clamshells.

Everything was strange that last night I saw them. I remember being freaked by shrieks of hysteria that turned into bubbles of laughter, coming from the darkened upstairs floor of the house. I remember the hate-filled glare of a saturnine man leaning in the corridor by the bathroom. I remember going to the kitchen to rummage for some ice and seeing something written in maple syrup on the bone-white door of the fridge, the letters running like thick dark blood. I peered closer, trying to read what it said, expecting something shocking and sinister, only to feel a sense of anticlimax when I deciphered the dripping, sticky word:

HEALTH

So much for Lucifer appearing uninvited at Hollywood parties.

But the second I dismissed the idea as dumb, a scampering, shadowy imp of fear started scratching about inside my mind again. The more I thought about it, the more the room, the house and everyone in it felt unsafe, and the sense kept expanding, engulfing me. Suddenly I caught sight of myself reflected in the floor-to-ceiling glass that separated the kitchen from the unlit rear garden, and saw how alone I was in that bright bare room. There was no one to care if I lived or died in this damned city. Without me even realizing it, everything in my world had begun to slip and slide into a howling, emptying abyss. There were no friends, no loyalties, no good intentions, only the prey and the preyed upon.

No haven, no shelter, just endless night, unforgiving and infinite.

If this was the effect of giving up marijuana, I thought, I really needed to start smoking again.

But the line of safety was thinner then. We felt much closer to destruction. These days we live with the danger while cheerfully ignoring the data.

I once attended a class on the structure of myths at UCLA where we discussed the theme of the uninvited guest, the phantom at the feast, the unclean in the temple, the witch at the christening, the vampire at the threshold, the doomsayer at the wedding, and all these myths shared one element in common; someone had to invite them in to begin with. I wondered who had provided an unwitting invitation here in California.

I remember that night there was a very pretty blond woman in the lounge—although I only saw her from the back—whom everyone wanted to talk to. One of her friends was drunkenly doing a trick with a lethal-looking table knife, and I thought what if he slips? And just as I was thinking that, I became aware of them, standing right alongside me. I turned and found myself beside the square-jawed one who looked like an actor. His gray deep-set eyes stared out at me very steadily, holding the moment. The light was low in the main hall, which was lit only by amber flames from an enormous carved fireplace. I saw the Satan sign glittering at his neck, and he smiled knowingly as I flinched.

“Who the hell are you?” I half-whispered, finally regaining my composure.

“Bobby.” He held out his hand. “You’re Julius.”

“How do you know who I am?”

“I have friends in the business. We know a lot of people.”

I didn’t like the way he said that. “I’ve seen you before,” I told him. “Seen your friends, too.”

“Yeah, they’re all here. We hang out together.” He pointed. “That’s Abby, Susan, Steve.”

They all looked over at me as if they’d picked up on their names being spoken. The effect of them moving with one shared mind was unnerving. I meant to say, “Who do you know here?” but instead I asked, “What are you here for?”

Bobby was silent for a moment, then smiled more broadly. “I think you know the answer to that. We’re here to taste death.”

“What do you mean?”

He looked away at the fire. “You have to know what dying is before you can know life, Julius.”

“I don’t understand you

.”

“I mean.” Bobby leaned in close and still, his eyes filling with morbid compassion as they stared deep into mine, “we’re leading the rise to power. We’ve already started the killing, and this city will become an inferno of revenge. The streets will run with blood. There will be a new holocaust, revolution in the streets, and the world will belong to the Fifth Angel.”

“Man, you’re crazy.” I shook my head, suddenly tired of this white supremacy crap. I’d just spent two months mofo-ing around in some Stepin Fetchit role given to me by rich white boys, and I guess I’d just had enough. “Bullshit,” I told him, “if the best thing you can do to start a revolution is shove a few drunks around at parties, you’re in trouble. I saw you at Dell’s place. I know you pushed that guy into the pool and broke his neck. I saw you in Silverlake, and at the house on Canon Drive where that guy was cut on the table. I know you don’t belong here, except to bring down chaos.”

“You’re right, we don’t belong here any more than you do,” he said, distracted now by something or someone moving past my left shoulder. “There’s no difference between us, brother. The rest of them are just little pigs.” He exchanged glances with the others, and the two girls turned to go, slipping out through the crowd. He pushed back to take his leave with them.

“Wait,” I called after him, anxious to keep him there. “How did you get in through security?”

Bobby looked over his shoulder, quiet and serious. “We have friends in all the places we’re not invited.”

“Nothing’s going to happen tonight, right? You’ve got to promise me that.”

“Nothing will happen tonight, Julius. We’re leaving.”

Inferno

Inferno The Best of the Best Horror of the Year

The Best of the Best Horror of the Year When Things Get Dark

When Things Get Dark A Whisper of Blood

A Whisper of Blood Echoes

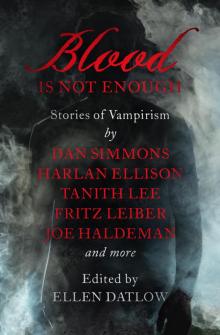

Echoes Blood Is Not Enough

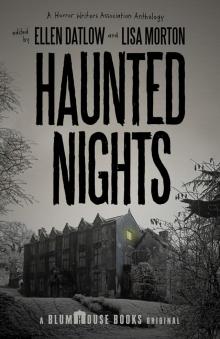

Blood Is Not Enough Haunted Nights

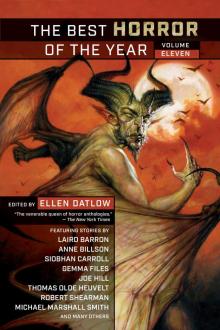

Haunted Nights The Best Horror of the Year Volume Eleven

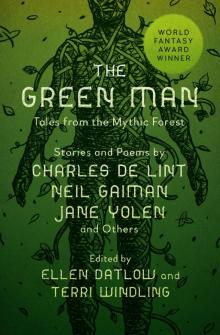

The Best Horror of the Year Volume Eleven The Green Man

The Green Man The Dark

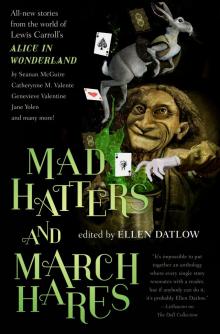

The Dark Mad Hatters and March Hares

Mad Hatters and March Hares Nebula Awards Showcase 2009

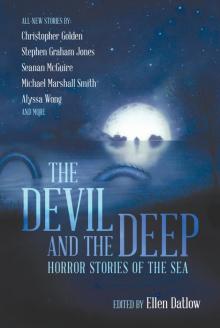

Nebula Awards Showcase 2009 The Devil and the Deep

The Devil and the Deep