- Home

- Ellen Datlow

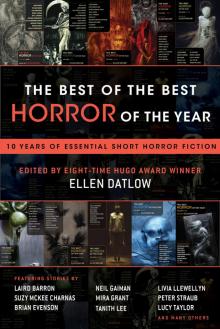

The Best of the Best Horror of the Year Page 19

The Best of the Best Horror of the Year Read online

Page 19

—Gimme a moment, I’m gonna be sick, Ruth says to no one in particular as she pushes away from the table. She doesn’t bother to close the front door as she walks down the rickety step into warm air and a hard gray sun. Ruth stumbles around the house to the back, where she stops, placing both hands against the wooden walls as she bends down, breathing hard, willing the vomit to stay down. Gradually, the thick sticky feeling recedes, and the tiny spots of black that dance around the corners of her vision fade and disappear. She stands, and starts down the dusty alley between the rows of houses and shacks.

Mountains, slung low against the far horizon of the earth, shimmering green and gray in the clear quiet light. Ruth stops at the edge of the alley, licking her lips as she stands and stares. Her back aches. Beyond the wave and curve of land, there is … Ruth bends over again, then squats, cupping her head in her hands, elbows on knees. This day, this day already happened. She’s certain of it. They drove, they drove along the dirt highway, the woman beside her, mouth running like a hurricane. They hung to the edges of the wide river, and then they rounded the last curve and stopped, and Ruth pooled out of the car like saliva around the heavy shaft of a cock, and she looked up, and, and, and.

And now some company brat is asking her if she’s ok, hey lady are you sick or just taking a crap, giggling as he speaks. Ruth stands up, and slaps him, crisp and hard. The boy gasps, then disappears between the houses. Ruth clenches her jaw, trying not to cry as she heads back around the house. Henry stands beside the open car door, ruin and rage dancing over his face. Her coat and purse and the basket of rolls have been tossed in the back seat, next to the wife. She’s already talking up a storm, rubbing her belly while she stares at Ruth’s, her eyes and mouth all smug and smarmy in that oily sisterly way, as if she knows. As if she could know anything at all.

The sky above is molten lead, bank after bank of roiling dark clouds vomiting out of celestial foundries. Ruth cranks the window lever, presses her nose against the crack. The air smells vast and earthen. The low mountains flow past in frozen antediluvian waves. Something about casseroles, the company bitch says. Something about gelatin and babies. Something about low tides. Ruth touches her forehead, frowns. There’s a hole in her memory, borderless and black, and she feels fragile and small. Not that she hates the feeling. Not entirely. Her hand rises up to the window’s edge, fingers splayed wide, as if clawing the land aside to reveal its piston-shaped core. The distant horizon undulates against the dull light, against her flesh, but fails to yield. It’s not its place to. She knows she’s already been to Beacon Rock. Lost deep inside, a trace remains. She got out of the car and she turned, and the mountains and the evergreens and thrusting up from the middle, a geologic eruption, a disruption hard and wide and high and then: nothing. Something was there, some thing was there, she knows she saw it, but the sinkhole in her mind has swallowed all but the slippery edges.

Her mouth twists, silent, trying to form words that would describe what lies beyond that absence of sound and silence and darkness and light, outside and in her head. As if words like that could exist. And now they are there, the car is rounding the highway’s final curves before the park. She rolls down the window all the way, and sticks her head and right arm out. A continent behind, her body is following her arm, like a larva wriggling and popping out of desiccated flesh, out of the car, away from the shouting, the ugly engine sounds, into the great shuddering static storm breaking all around. She saw Beacon Rock, then and now. The rest, they all saw the rock, but she saw beyond it, under the volcanic layers she saw it, and now she feels it, now she hears, and it hears her, too.

Falling, she looks up as she reaches out, and—

The clock on the bookcase chimes ten. Her fingers, cramping, slowly uncurl from a cold coffee cup. Henry is in the other room, getting dressed. Ruth hears him speaking to her, his voice tired water dribbling over worn gravel. Something about the company picnic. Something about malformed, moldering backwaters of trapped space and geologic time. Something about the rock.

Tiny spattering sounds against paper make her stare up to the ceiling, then down at the table. Droplets of blood splash against the open page in her scrapbook. Ruth raises her hand to her nose, pinching the nostrils as she raises her face again. Blood slides against the back of her throat, and she swallows. On the clipping, the young socialite’s face disappears in a sudden crimson burst, like a miniature solar flare erupting around her head, enveloping her white-teethed smile. Red coronas everywhere, on her linen-draped limbs, on the thick bark of the palm, on the phosphorus-bright velvet lawn. Somewhere outside, a plane drones overhead, or so it sounds like a plane. No, a plain, a wide expanse of plain, a moorless prairie of static and sound, all the leftover birth and battle and death cries of the planet, jumbled into one relentless wave streaming forth from some lost and wayward protrusion at the earth’s end. Ruth pushes the scrapbook away and wipes her drying nose with the edges of her cardigan and the backs of her hands. Her lips open and close in silence as she tries to visualize, to speak the words that would describe what it is that’s out there, what waits for her, high as a mountain and cold and alone. What is it that breathes her name into the wind like a mindless burst of radio static, what pulses and booms against each rushing thrust of the wide river, drawing her body near and her mind away? She saw and she wants to see it again and she wants to remember, she wants to feel the ancient granite against her tongue, she wants to rub open-legged against it until it enters and hollows her out like a mindless pink shell. She wants to fall into it, and never return here again.

—Not again, she says to the ceiling, to the walls, as Henry opens the door.

—Not again, not again, not again.

He stares at her briefly, noting the red flecks crusting her nostrils and upper lip.

—Take care of that, he says; grabbing his coat, he motions at the kitchen sink. Always the same journey, and the destination never any closer. Ruth quickly washes her face, then slips out the door behind him into the hot, sunless morning. The company wife is in the back, patting the seat next to her. Something about the weather, she says, her mouth spitting out the words in little squirts of smirk while her eyes dart over Ruth’s wet red face. She thinks she knows what that’s all about. Lots of company wives walk into doors. Something about the end of Prohibition. Something about the ghosts of a long-ago war. Ruth sits with her head against the window, eyes closed, letting the one-sided conversation flow out of the woman like vomit. Her hand slips under the blue-checked dish towel covering the rolls, and she runs her fingers over the flour-dusted tops. Like cobblestones. River stones, soft water-licked pebbles, thick gravel crunching under her feet. She pushes a finger through the soft crust of a roll, digging down deep into its soft middle. That’s what it’s doing to her, out there, punching through her head and thrusting its basalt self all through her, pulverizing her organs and liquefying her heart. The car whines and rattles as it slams in and out of potholes, gears grinding as the company man navigates the curves. Eyes still shut, Ruth runs a fingertip over each lid, pressing in firm circles against the skin, feeling the hard jelly mounds roll back and forth at her touch until they ache. The landscape outside reforms itself as a negative against her lids, gnarled and blasted mountains rimmed in small explosions of sulfur-yellow light. She can see it, almost the tip of it, pulsating with a monstrous beauty in the distance, past the last high ridges of land. Someone else must have known, and that’s why they named it so. A wild perversion of nature, calling out through the everlasting sepulcher of night, seeking out and casting its blind gaze only upon her—

The company wife is grabbing her arm. The car has stopped. Henry and the man are outside, fumbling with the smoking engine hood. Ruth wrests her arm away from the woman’s touch, and opens the door. The rest of the caravan has passed them by, rounded the corner into the park. Ruth starts down the side of the road, slow, nonchalant, as if taking in a bit of air. As if she could. The air has bled out, and only the pounding

static silence remains, filling her throat and lungs with its hadal-deep song.

—I’m coming, she says to it.

—I’m almost here. She hears the wife behind her, and picks up her pace.

—You gals don’t wander too far, she hears the company man call out.

—We should have this fixed in a jiffy.

Ruth kicks her shoes off and runs. Behind her, the woman is calling out to the men. Ruth drops her purse. She runs like she used to when she was a kid, a freckled tomboy racing through the wheat fields of her father’s farm in North Dakota. She runs like an animal, and now the land and the trees and the banks of the river are moving fast, slipping past her piston legs along with the long bend of the road. Her lungs are on fire and her heart is all crazy and jumpy against her breasts and tears streak into her mouth and nose and it doesn’t matter because she is so close and it’s calling her with the hook of its song and pulling her reeling her in and Henry’s hand is at the back of her neck and there’s gravel and the road smashing against her mouth and blood and she’s grinding away and kicking and clawing forward and all she has to do is lift up her head just a little bit and keep her eyes shut and she will finally see—

Ruth’s hands are clasped tight in her lap. Scum floats across the surface of an almost empty cup of coffee. A sob escapes her mouth, and she claps her hand over it, hitching as she pushes it back down. This small house. This small life. This cage. She can’t do it anymore. The clock on the bookcase chimes ten.

—I swear, this is the last time, Ruth says, wiping the tears from her cheeks. The room is empty, but she knows who she’s speaking to. It knows, too.

—I know how to git to you. I know how to see you. This is the last goddamn day.

On the kitchen table before her is the scrapbook, open to her favorite clipping. Ruth peels it carefully from the yellowing page and holds it up to the light. Somewhere in the southern tropics: a pretty young woman in stained white linens, lounging on a bench that encircles the impossibly thick trunk of a tree that has no beginning or end, whose roots plunge so far beyond the ends of earth and time that, somewhere in the vast cosmic oceans above, they loop and descend and transform into the thick fronds and leaves that crown the woman’s head with dappled shadow. All around the woman and the tree, drops of dried blood are spattered across the paper like the tears of a dying sun. The woman’s face lies behind one circle of deep brown, earth brown, wood brown, corpse brown. She is smiling, open-eyed, breathing it all in. Ruth balls the clipping up tight, then places it in her mouth, chewing just a bit before she swallows. There is no other place the woman and the palm have been, that they will ever be. Alone, apart, removed, untouched. All life here flows around them, utterly repelled. They cannot be bothered. It is of no concern to them. What cycle of life they are one with was not born in this universe.

In the other room, Henry is getting dressed. If he’s talking, she can’t hear. Everywhere, black static rushes through the air, strange equations and latitudes and lost languages and wondrous geometries crammed into a silence so old and deep that all other sounds are made void. Ruth closes the scrapbook and stands, wiping the sweat from her palms on her Sunday dress. There is a large knife in the kitchen drawers, and a small axe by the fireplace. She chooses the knife. She knows it better, she knows the heft of it in her hand when slicing into meat and bone. When he finally opens the door and steps into the small room, she’s separating the rolls, the blade slipping back and forth through the powdery grooves. Ruth lifts one up to Henry, and he takes it. It barely touches his mouth before she stabs him in the stomach, just above the belt, where nothing hard can halt its descent. He collapses, and she falls with him, pulling the knife out and sitting on his chest as she plunges it into the center of his chest, twice because she isn’t quite sure where his heart is, then once at the base of his throat. Blood, like water gurgling over river stones, trickling away to a distant, invisible sea. That, she can hear. Ruth wipes the blade on her dress as she rises, then places it on the table, picks up the basket and walks to the front door. She opens it a crack.

—Henry’s real sick, she says to the company man. We’re gonna stay home today. She gives him the rolls, staring hard at the company wife in the back seat as he walks back to his car. The wife looks her over, confused. Ruth smiles and shuts the door. That bitch doesn’t know a single thing.

Ruth slips out the back, through the window of their small bedroom. The caravan of cars is already headed toward the highway, following the Columbia downstream toward Beacon Rock. They’ll never make it to their picnic. They’ll never see it. They never do. She moves through the alley, past the last sad row of company houses and into the tall evergreens that mark the end of North Bonneville. With each step into the forest, she feels the weight of the town fall away a little, and something vast and leviathan burrows deeper within, filling up the unoccupied space. When she’s gone far and long enough that she no longer remembers her name, she stops, and presses her fingers deep into her sockets, scooping her eyes out and pinching off the long ropes of flesh that follow them out of her body like sticky yarn. What rushes from her mouth might be screaming or might be her soul, and it is smothered in the indifferent silence of the wild world.

And now it sees, and it moves in the way it sees, floating and darting back and forth through the hidden phosphorescent folds of the lands within the land, darkness punctured and coruscant with unnamable colors and light, its dying flesh creeping and hitching through forests petrified by the absence of time, past impenetrable ridges of mountains whose needle-sharp peaks cut whorls in the passing rivers of stars. A veil of flies hovers about the caves of its eyes and mouth, rising and falling with every rotting step, and bits of flesh scatter and sink to the earth like barren seeds next to its pomegranate blood. If there is pain, it is beyond such narrow knowledge acknowledgement of its body. There is only the bright beacon of light and thunderous song, the sonorous ringing of towering monolithic basalt breathing in and out, pushing the darkness away. There is, finally, past the curvature of the overgrown wild, a lush grass plain of emerald green, ripe and plump under a fat hot sun, a wide bench of polished wood, and a palm tree pressing in a perfect arc against its small back, warm and worn and hard like ancient stone. When it looks up, it cannot see the tree’s end. Its vision rises blank and wondrous with branches as limitless as its both their dreams, past all the edges of all time, and this is the way it should be.

SHEPHERDS’ BUSINESS

STEPHEN GALLAGHER

Picture me on an island supply boat, one of the old Clyde Puffers seeking to deliver me to my new post. This was 1947, just a couple of years after the war, and I was a young doctor relatively new to General Practice. Picture also a choppy sea, a deck that rose and fell with every wave, and a cross-current fighting hard to turn us away from the isle. Back on the mainland I’d been advised that a hearty breakfast would be the best preventative for seasickness and now, having loaded up with one, I was doing my best to hang onto it.

I almost succeeded. Perversely, it was the sudden calm of the harbour that did for me. I ran to the side and I fear that I cast rather more than my bread upon the waters. Those on the quay were treated to a rare sight; their new doctor, clinging to the ship’s rail, with seagulls swooping in the wake of the steamer for an unexpected water-borne treat.

The island’s resident Constable was waiting for me at the end of the gangplank. A man of around my father’s age, in uniform, chiselled in flint and unsullied by good cheer. He said, “Munro Spence? Doctor Munro Spence?”

“That’s me,” I said.

“Will you take a look at Doctor Laughton before we move him? He didn’t have too good a journey down.”

There was a man to take care of my baggage, so I followed the Constable to the Harbourmaster’s house at the end of the quay. It was a stone building, square and solid. Doctor Laughton was in the Harbourmaster’s sitting room behind the office. He was in a chair by the fire with his feet on a stool and a rug o

ver his knees and was attended by one of his own nurses, a stocky red-haired girl of twenty or younger.

I began, “Doctor Laughton. I’m …”

“My replacement, I know,” he said. “Let’s get this over with.”

I checked his pulse, felt his glands, listened to his chest, noted the signs of cyanosis. It was hardly necessary; Doctor Laughton had already diagnosed himself, and had requested this transfer. He was an old-school Edinburgh-trained medical man, and I could be sure that his condition must be sufficiently serious that ‘soldiering on’ was no longer an option. He might choose to ignore his own aches and troubles up to a point, but as the island’s only doctor he couldn’t leave the community at risk.

When I enquired about chest pain he didn’t answer directly, but his expression told me all.

“I wish you’d agreed to the aeroplane,” I said.

“For my sake or yours?” he said. “You think I’m bad. You should see your colour.” And then, relenting a little, “The airstrip’s for emergencies. What good’s that to me?”

I asked the nurse, “Will you be travelling with him?”

“I will,” she said. “I’ve an Aunt I can stay with. I’ll return on the morning boat.”

Two of the men from the Puffer were waiting to carry the doctor to the quay. We moved back so that they could lift him between them, chair and all. As they were getting into position Laughton said to me, “Try not to kill anyone in your first week, or they’ll have me back here the day after.”

I was his locum, his temporary replacement. That was the story. But we both knew that he wouldn’t be returning. His sight of the island from the sea would almost certainly be his last.

Once they’d manoeuvred him through the doorway, the two sailors bore him with ease toward the boat. Some local people had turned out to wish him well on his journey.

Inferno

Inferno The Best of the Best Horror of the Year

The Best of the Best Horror of the Year When Things Get Dark

When Things Get Dark A Whisper of Blood

A Whisper of Blood Echoes

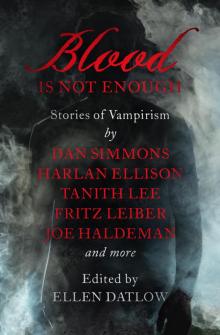

Echoes Blood Is Not Enough

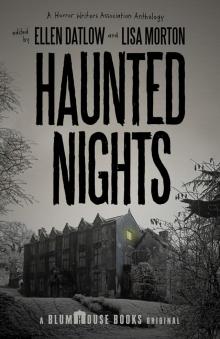

Blood Is Not Enough Haunted Nights

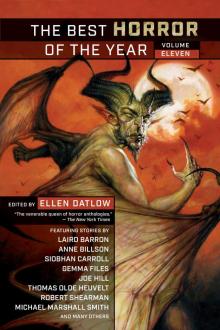

Haunted Nights The Best Horror of the Year Volume Eleven

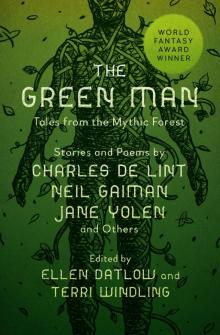

The Best Horror of the Year Volume Eleven The Green Man

The Green Man The Dark

The Dark Mad Hatters and March Hares

Mad Hatters and March Hares Nebula Awards Showcase 2009

Nebula Awards Showcase 2009 The Devil and the Deep

The Devil and the Deep