- Home

- Ellen Datlow

The Green Man Page 2

The Green Man Read online

Page 2

Mythic tales of forest outlaws are a sub-category of wild man legends, although in such stories (Robin Hood, for example) the hero is generally a civilized man compelled, through an act of injustice, to seek the wild life. Magical tales of hermits and woodland mystics form another sub-category, and Christian legends are filled with tales of saints living in the wilderness on a diet of honey and acorns. This, again, is bolstered by the actual experience of people in earlier times, when it was not uncommon for folk marginalized by the community (mystics, herbalists or witches, widows, eccentrics, and simpletons) to live in the wilds beyond the village, either by choice or by necessity. An elderly neighbor of mine in Devon, England, remembers such a figure from her youth—a harmless old soul who lived in a cave and was believed to have prophetic powers.

To the German Romantics, forests held the soul of myth and thus of volk (folk) culture, believed to be more pure and true than the artifice of civilization. E.T.A. Hoffman, Ludwig Tieck, Baron Friedrich de la Motte Fouqué, Novalis, and other German writers entered the fairy tale forest to create mystical, darkly magical works making deft use of mythic archetypes. In the early nineteenth century, the Brothers Grimm published their famous German folklore collections, full of tales in which a journey to the dark woods was the catalyst for magic and transformation. The passion for folklore spread across Europe, touching every area of popular arts in addition to fostering a new academic climate for collection of oral tales and ballads. In Scotland, the Reverend George MacDonald, inspired by the works of the German Romantics, began to write folkloric stories—like “The Light Princess” and “The Golden Key"—which are now classics of magical literature. In the faery woods of MacDonalds imagination, talking trees (both wondrous and wicked) are drawn directly from mythic archetypes, forming part of a literary tradition that runs from the prophetic trees in the magical adventures of Alexander the Great, through the “Wood of Suicides” in Dante’s Inferno, to the Ents in Tolkien’s Lord of the Rings. The Victorian painter Edward Burne-Jones and his fellow Pre-Raphaelite artists returned again and again to the Archetypal Forest in their paintings, poetry, and prose—including novels such as The Wood Beyond the World by Burne-Jones’s great friend William Morris. As the century turned, Celtic Twilight writers like the Irish poet William Butler Yeats found magic in the twilight woods with which to fuel their art. In the early twentieth century, writers such as Hope Mirrlees (Lud in the Mist), James Stephens (The Crock of Gold), and Lord Dunsany (The King of Elfland’s Daughter) created modern mythic tales to explore the woodlands that lie (to borrow Dunsany’s phrase) “beyond the fields we know.” Then three Oxford dons came along—J.R.R. Tolkien, C.S. Lewis, and Charles Williams—calling themselves the Inklings, whose work has profoundly influenced most magical fiction written since.

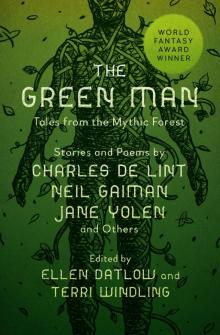

It is the challenging task of modern fantasists to assimilate the works produced by these three (Tolkien in particular), while avoiding the pitfall of merely producing pale imitations of it. Modern writers who have managed this most successfully (Alan Garner, Ursula K. Le Guin, Jane Yolen, Philip Pullman, etc.) are those familiar with the mythic source material which the past masters used to such great effect—as well as those for whom a strongly personal vision shines through Professor Tolkien’s long shadow.

Neil Gaiman is a good example of a modern myth-maker who avoids being derivative, even when he gives a tip of the hat to Dunsany, Mirrlees, and Christina Rossetti, as in his charming faery novel Stardust. This story, set in an English woodland at the Wall separating our world from faeryland, reads like a classic nineteenth-century story yet is utterly fresh and original. Stardust began as a collaborative work first published in narrative graphic form with enchanting paintings by Charles Vess. The woodland created by this talented pair is not a generic Fantasy Forest—through Gaiman’s clever yet gentle prose and Vess’s Rackham-flavored pictures these woods are specifically English and yet archetypal as well, filled with true magic. The spirit of the woodland is also a captivating presence in the Japanese animated film Princess Mononoke, with its English screenplay adapted by Neil Gaiman, a deeply folkloric work in which all the power and terror of the Mythic Forest is brought vividly to life. Robert Holdstock is a writer who has traveled deeper into the woods than any other mythic writer, and the books of his Mythago Wood sequence are essential reading, as well as his Breton novel Merlin’s Wood.

Charles de Lint writes interstitial works which bring the potent archetypes of the mythic woods into modern urban settings, particularly in his novels Forests of the Heart and Greenmantle. In The Wild Wood, inspired by the art of Brian Froud, de Lint takes us deep into the woods of northern Canada—a prismatic landscape where magic and madness waits, as in shamanic tales of old.

The woodlands of Patricia A. McKillip’s tales are some of the finest in fantasy literature; I recommend her novels Winter Rose and The Book of Atrix Wolfe, as well as her unusual contemporary story Stepping from the Shadows. I also recommend Sean Russell’s World without End and its sequel Sea without a Shore; Rumours of Spring by Richard Grant; Engine Summer by John Crowley; The Word for World Is Forest by Ursula K. Le Guin; Cloven Hooves by Megan Lindholm; The Stone Silenus by Jane Yolen; Enchantments by Orson Scott Card; and Thomas the Rhymer by Ellen Kushner. The Bloody Chamber by Angela Carter and Red as Blood by Tanith Lee are good story collections filled with deliciously dark, Freudian flavored fairy tale woods. And for fine novels set in American wilderness, try: Wild Life by Molly Gloss, Nadya by Pat Murphy, The Flight of Michael McBride by Midori Snyder, and Power by Linda Hogan.

Visual artists have also been caught by the powerful spell of the Mythic Forest. In addition to the art of Charles Vess, which beautifully ornaments this volume, I recommend seeking out art books on the work of two English sculptors: Andy Goldsworthy (Wood) and Peter Randall-Page (Granite Song, available through the Internet Bookshop, www.book-shop.co.uk), as well as the Scottish photographer Thomas Joshua Cooper (Between Dark and Dark), British painter Brian Froud (Good Faeries/Bad Faeries, and Faeries, with Alan Lee), and the fairy tale art of “Golden Age” illustrators Arthur Rackham, Kay Nielsen, and Edmund Dulac.

For further reading on the subject of the Green Man, forest folklore, and nature mythology, try: Green Man by William Anderson and Clive Hicks, The Wisdom of Trees: Mysteries, Magic and Medicine by Jane Clifford, Celtic Sacred Landscape by Nigel Pennick, A Dictionary of Nature Myths by Tamra Andrews, Forests: The Shadow of Civilization by Robert Pogue Harrison, Meetings with Remarkable Trees by Robert Packenham, Discovering the Folklore of Plants by Margaret Baker, The Practice of the Wild by Gary Snyder, The Spell of the Sensuous by David Abram, The Power of Myth by Joseph Campbell, and The White Goddess by Robert Graves.

The Mythic Forest is every forest—we enter it whenever we enter the woods. The Green Man dwells there, called by different names all over the world. When we hear the rustling of the leaves, we’re still hearing the Oracle, and the oaks are still the home of faeries … or at least of tales about them. In California, there are living trees, the bristlecone pines, that are thousands and thousands of years old. So are the stories of the trees. They are ancient, deeply rooted in the loam, yet still unfurling bright new leaves.

Going Wodwo

Neil Gaiman

Shedding my shirt, my book, my coat, my life,

Leaving them, empty husks and fallen leaves,

Going in search of food and for a spring

Of sweet water.

I’ll find a tree as wide as ten fat men,

Clear water rilling over its grey roots.

Berries I’ll find, and crab apples and nuts,

And call it home.

I’ll tell the wind my name, and no one else.

True madness takes or leaves us in the wood

halfway through all our lives. My skin will be

my face now.

I must be nuts. Sense left with shoes and house,

my guts are cramped. I’ll stumble through the green

back to my ro

ots, and leaves, and thorns, and buds,

and shiver.

I’ll leave the way of words to walk the wood.

I’ll be the forest’s man, and greet the sun,

And feel the silence blossom on my tongue

like language.

Neil Gaiman is a transplanted Briton currently living in the American Midwest. He is the author of the award-winning Sandman series of graphic novels, and of the novels Neverwhere and American Gods. American Gods won the Hugo, the Bram Stoker, the SFX, the Nebula, and the Locus awards. His most recent novel, Coraline, intended for children of all ages, won the Bram Stoker Award in the Work for Young Readers category, and was a Finalist for the World Fantasy Award. Gaiman’s collaborations with artist Dave McKean include Mr. Punch, the children’s books The Day I Swapped My Dad for 2 Goldfish and The Wolves in the Walls, and their new film Mirror-Mask.

In addition, Gaiman is a talented poet and short story writer whose work has been published in a number of the Datlow/Windling adult fairy tale anthologies and in several editions of The Year’s Best Fantasy and Horror. His short work has been collected in Angels and Visitations and Smoke and Mirrors.

His Web site is www.neilgaiman.com

Author’s Note:

A wodwo (or wodwose, or woodwose) was a medieval wild man of the woods. Sometimes they are identified with the Green Men.

This came from wondering what it would mean to be a wodwo now; and from the carvings of Green Men as human-faced men with leaves growing from their mouths.

Grand Central Park

Delia Sherman

When I was little, I used to wonder why the sidewalk trees had iron fences around them. Even a city kid could see they were pretty weedy looking trees. I wondered what they’d done to be caged up like that, and whether it might be dangerous to get too close to them.

So I was pretty little, okay? Second grade, maybe. It was one of the things my best friend and I used to talk about, like why it’s so hard to find a particular city on a map when you don’t already know where it is, and why the fourth graders thought Mrs. Lustenburger’s name was so hysterically funny. My best friend’s name was (is) Galadriel, which isn’t even remotely her fault, and only her mother calls her that anyway. Everyone else calls her Elf.

Anyway. Trees. New York. Have I said I live in New York? I do. In Manhattan, on the West Side, a couple blocks from Central Park.

I’ve always loved Central Park. I mean, it’s the closest to nature I’m likely to get, growing up in Manhattan. It’s the closest to nature I want to get, if you must know. There’s wild things in it—squirrels and pigeons and like that, and trees and rocks and plants. But they’re city wild things, used to living around people. I don’t mean they’re tame. I mean they’re streetwise. Look. How many squished squirrels do you see on the park transverses? How many do you see on any suburban road? I rest my case.

Central Park is magic. This isn’t a matter of opinion, it’s the truth. When I was just old enough for Mom to let me out of her sight, I had this place I used to play, down by the boat pond, in a little inlet at the foot of a huge cliff. When I was in there, all I could see was the water all shiny and sparkly like a silk dress with sequins and the great grey hulk of the rock behind me and the willow tree bending down over me to trail its green-gold hair in the water. I could hear people splashing and laughing and talking, but I couldn’t see them, and there was this fairy who used to come and play with me.

Mom said my fairy friend came from me being an only child and reading too many books, but all I can say is that if I’d made her up, she would have been less bratty. She had long Saran-Wrap wings like a dragonfly, she was teensy, and she couldn’t keep still for a second. She’d play princesses or Peter Pan for about two minutes, and then she’d get bored and pull my hair or start teasing me about being a big, galumphy, deaf, blind human being or talking to the willow or the rocks. She couldn’t even finish a conversation with a butterfly.

Anyway, I stopped believing in her when I was about eight, or stopped seeing her, anyway. By that time I didn’t care because I’d gotten friendly with Elf, who didn’t tease me quite as much. She wasn’t into fairies, although she did like to read. As we got older, mostly I was grateful she was willing to be my friend. Like, I wasn’t exactly Ms. Popularity at school. I sucked at gym and liked English and like that, so the cool kids decided I was a super-geek. Also, I wear glasses and I’m no Ally McBeal, if you know what I mean. I could stand to lose a few pounds—none of your business how many. It wasn’t safe to be seen having lunch with me, so Elf didn’t. As long as she hung with me after school, I didn’t really care all that much.

The inlet was our safe place, where we could talk about whether the French teacher hated me personally or was just incredibly mean in general and whether Patty Gregg was really cool, or just thought she was. In the summer, we’d take our shoes off and swing our feet in the water that sighed around the roots of the golden willow.

So one day we were down there, gabbing as usual. This was last year, the fall of eleventh grade, and we were talking about boyfriends. Or at least Elf was talking about her boyfriend and I was nodding sympathetically. I guess my attention wandered, and for some reason I started wondering about my fairy friend. What was her name again? Bubble? Burble? Something like that.

Something tugged really hard on about two hairs at the top of my head, where it really hurts, and I yelped and scrubbed at the sore place. “Mosquito,” I explained. “So what did he say?”

Oddly enough, Elf had lost interest in what her boyfriend had said. She had this look of intense concentration on her face, like she was listening for her little brother’s breathing on the other side of the bedroom door. “Did you hear that?” she whispered.

“What? Hear what?”

“Ssh.”

I sshed and listened. Water lapping; the distant creak of oarlocks and New Yorkers laughing and talking and splashing. The wind in the willow leaves whispering, ssh, ssh. “I don’t hear anything,” I said.

“Shut up,” Elf snapped. “You missed it. A snapping sound. Over there.” Her blue eyes were very big and round.

“You’re trying to scare me,” I accused her. “You read about that woman getting mugged in the park, and now you’re trying to jerk my chain. Thanks, friend.”

Elf looked indignant. “As if!” She froze like a dog sighting a pigeon. “There.”

I strained my ears. It seemed awfully quiet all of a sudden. There wasn’t even a breeze to stir the willow. Elf breathed, “Omigod. Don’t look now, but I think there’s a guy over there, watching us.”

My face got all prickly and cold, like my body believed her even though my brain didn’t. “I swear to God, Elf, if you’re lying, I’ll totally kill you.” I turned around to follow her gaze. “Where? I don’t see anything.”

“I said, don’t look,” Elf hissed. “He’ll know.”

“He already knows, unless he’s a moron. If he’s even there. Omigod!”

Suddenly I saw, or thought I saw, a guy with a stocking cap on and a dirty, unshaven face peering around a big rock. It was strange. One second, it looked like a guy, the next, it was more like someone’s windbreaker draped over a bush. But my heart started to beat really fast anyway. There weren’t that many ways to get out of that particular little cove if you didn’t have a boat.

“See him?” she hissed triumphantly.

“I guess.”

“What are we going to do?”

Thinking about it later, I couldn’t quite decide whether Elf was really afraid, or whether she was pretending because it was exciting to be afraid, but she sure convinced me. If the guy was on the path, the only way out was up the cliff. I’m not in the best shape and I’m scared of heights, but I was even more scared of the man, so up we went.

I remember that climb, but I don’t want to talk about it. I thought I was going to die, okay? And I was really, really mad at Elf for putting me though this, like if she hadn’t noticed the guy, he

wouldn’t have been there. I was sweating, and my glasses kept slipping down my nose and…. No. I won’t talk about it. All you need to know is that Elf got to the top first and squirmed around on her belly to reach down and help me up.

“Hurry up,” she panted. “He’s behind you. No, don’t look”—as if I could even bear to look all that way down—“just hurry.”

I was totally winded by the time I got to the top and scrambled to my feet, but Elf didn’t give me time to catch my breath. She grabbed my wrist and pulled me to the path, both of us stumbling as much as we were running.

It was about this time I realized that something really weird was going on. Like, the path was empty, and it was two o’clock in the afternoon of a beautiful fall Saturday, when Central Park is so full of people it’s like Times Square with trees. And I couldn’t run, just like you can’t run in dreams. Suddenly, Elf tripped and let go of me. The path shook itself, and she was gone. Poof. Nowhere in sight.

By this time, I’m freaked totally out of my mind. I look around, and there’s this guy, hauling himself over the edge of the cliff, stocking cap jammed down over his head, face grayskinned with dirt, half his teeth missing. I don’t know why I didn’t scream—usually, it’s pitiful how easy it is to make me scream—I just turned around and ran.

Now, remember that there’s about fifty million people in the park that day. You’d think I would run into one or two, which would mean safety because muggers don’t like witnesses. But no.

Inferno

Inferno The Best of the Best Horror of the Year

The Best of the Best Horror of the Year When Things Get Dark

When Things Get Dark A Whisper of Blood

A Whisper of Blood Echoes

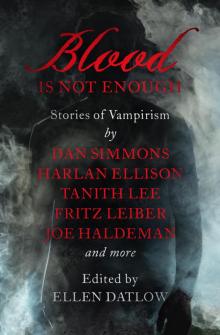

Echoes Blood Is Not Enough

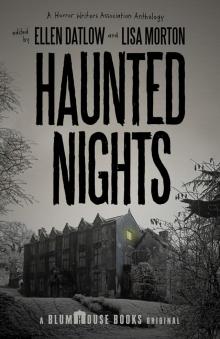

Blood Is Not Enough Haunted Nights

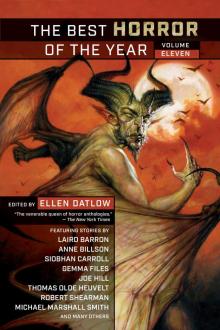

Haunted Nights The Best Horror of the Year Volume Eleven

The Best Horror of the Year Volume Eleven The Green Man

The Green Man The Dark

The Dark Mad Hatters and March Hares

Mad Hatters and March Hares Nebula Awards Showcase 2009

Nebula Awards Showcase 2009 The Devil and the Deep

The Devil and the Deep