- Home

- Ellen Datlow

The Best of the Best Horror of the Year Page 22

The Best of the Best Horror of the Year Read online

Page 22

“My son had shipped on a stormcrow ship. It was on the homeward leg of the journey, with him bringing me his wages—for he was too young to have spent them on women and on grog, like his father—that the storm hit.

“He was the smallest one in the lifeboat.

“They said they drew lots fairly, but I do not believe it. He was smaller than them. After eight days adrift in the boat, they were so hungry. And if they did draw lots, they cheated.

“They gnawed his bones clean, one by one, and they gave them to his new mother, the sea. She shed no tears and took them without a word. She’s cruel.

“Some nights I wish he had not told me the truth. He could have lied.

“They gave my boy’s bones to the sea, but the ship’s mate—who had known my husband, and known me too, better than my husband thought he did, if truth were told—he kept a bone, as a keepsake.

“When they got back to land, all of them swearing my boy was lost in the storm that sank the ship, he came in the night, and he told me the truth of it, and he gave me the bone, for the love there had once been between us.

“I said, you’ve done a bad thing, Jack. That was your son that you’ve eaten.

“The sea took him too, that night. He walked into her, with his pockets filled with stones, and he kept walking. He’d never learned to swim.

“And I put the bone on a chain to remember them both by, late at night, when the wind crashes the ocean waves and tumbles them on to the sand, when the wind howls around the houses like a baby crying.”

The rain is easing, and you think she is done, but now, for the first time, she looks at you, and appears to be about to say something. She has pulled something from around her neck, and now she is reaching it out to you.

“Here,” she says. Her eyes, when they meet yours, are as brown as the Thames. “Would you like to touch it?”

You want to pull it from her neck, to toss it into the river for the mudlarks to find or to lose. But instead you stumble out from under the canvas awning, and the water of the rain runs down your face like someone else’s tears.

THE MAN FROM THE PEAK

ADAM GOLASKI

The sun left tatters in shades of red across the sky; tatters that shriveled through purple, indigo—to black. The stars didn’t come out. Instead, oil-gray clouds. I kept the car going, up, steering around the worst ruts and rocks in the road. I drove under the no trespassing sign, kept driving up. The forest around me was thick—the leaves had come in, hearty and wet: spring. I wondered if this would be the last time I’d make the drive up to Richard’s. I thought so. Richard was leaving. Moving east. So, a farewell bash. Sarah would be there, too. With a sound like marbles clicking, or teeth, the wine bottle and the whisky bottle on the passenger seat bumped against each other.

Richard’s house stood in the shadow of the mountain’s peak. I turned off the car and sat, let my eyes adjust to the darkness, listened to cooling engine skitter. The walk to Richard’s was lined with paper lanterns—no doubt Sarah’s touch. I grabbed the bottles, set them on the roof of the car, lit a cigarette and looked up the peak. I heard people talking—some of the voices outside, from the hot tub, no doubt, and muted voices from the house. There were a dozen cars parked in front of my own. I opened the back door of the car and took out a small package—a book for Sarah, a collection of short stories she and I had talked about the last time the three of us—Richard, Sarah and I—had been together. I tucked the book under my arm, took the bottles and walked up to the house. I rang the bell and a woman wearing a bikini opened the door. She looked at me—looked me up and down as if I were wearing a bikini—laughed a little and brushed past me. As she passed, she asked, “Did you bring your suit?”

The house was long and narrow. To my left was the guest room, to my right a kitchen and a television room/bar. Michael, an old friend of Richard’s who I’d come to like, was busy mixing drinks. He’d explained to me once that he took up the role of bartender at parties so he could get to know all the women. I approached the bar and said, “I’d say the hot tub is where you want to be tonight.” Michael nodded, ruefully. I handed Michael the bottles I’d brought. “Good stuff,” he said. “Good to see you,” he said. I shook his hand and patted his shoulder. “What’ll you have?” he asked. “A glass of that whiskey,” I said. He said, “Try this instead,” and poured from an already open bottle. I put my cigarette out in a red-glass ashtray by the bar and had a sip. I nodded my appreciation. “I should announce myself,” I said, and backed away.

The living room: a large, open space dominated by a fat couch and a grand piano (Richard didn’t play). Sarah was on the couch drinking wine. When she saw me, she stood, crossed the room with a quick, woozy stride and put her arms around me.

“Watch the wine,” I said.

She stepped back from me, a wounded expression on her face. I took her glass and rested it on the piano. She put her arms around me again and said, “I get so excited when you come. I always do. It’s so silly. I always am so excited to see you.”

“It’s good to see you too.” We kissed, as we did whenever we saw each other; I’m not sure how this greeting got started, but our kisses were long and on the lips; she’d been dating Richard as long as I’d known her.

“Have you seen Richard yet?” she asked.

“I just got here.”

“Can I?” She tapped the cigarette box in my breast pocket. She slipped her fingers into the pocket and smiled at me. “You always have the best cigarettes.” As she lit up, she eyed the wrapped package under my arm.

“It’s for you,” I said.

She unwrapped my gift, dropped the brown paper to the floor. “You found a copy,” she said. She opened the book, careful with the spine, a delicate touch on the yellow edge of each page she turned over. “You’re the only one who ever gets me books.” She tapped her necklace: an elegant, expensive silver knot. “Richard always buys me jewelry,” she said, with a frown.

We caught up, a little; a little about Richard’s preparations for leaving, though we skirted the issue of whether or not she’d be going. We would have that conversation later. I needed to drink a little more, to meet everyone. I looked past Sarah, at the women on the couch. Sarah said, “That one’s Carmilla—she’s a stunning bore—and that’s Kat—fun, fun, fun. They’re friends of Richard’s. From where, I do not know. Come, I need more wine.” We left her glass on the piano, made our way up to the bar. She fell into a conversation with Michael. I walked off—I didn’t feel like standing around while Sarah and Michael talked.

Richard was in the yard, beer in hand, talking with someone I didn’t know. Just behind him was the hot tub. The woman who’d answered the door was in the tub with a couple of guys. Before Richard spotted me, the woman said, “You should come in, it’s perfect, cold outside, warm in here.” She giggled. One of the guys leaned over and whispered to her. She pushed him away.

“David, you made it,” Richard said.

“I wouldn’t miss it.”

“Well I’m glad, you know.”

He introduced me to his friend, and to the guys in the tub. He didn’t know the woman’s name and she didn’t supply it. “Come on and sit,” he said to me.

I sat on a cooler. Richard and his friend were talking about Boston, where Richard was moving. I’d never been to Boston, I told them, though I’d heard it was like San Francisco. We talked about San Francisco, Seattle, Portland.

The woman in the hot tub interrupted us and asked me to get her a beer. I got up to get a beer from the cooler. She stood. She was very thin, no hips, but gifted with significant breasts. She leaned forward—bent at the waist without bending her knees—and brought her bosom to my face. Freckles swirled into the dark line of her cleavage. “Thank you so much,” she said, and took the beer. The guys in the tub were happily gazing up at her tiny bottom—those men were nothing to her, made to carry her bags and perform rudimentary tasks while she gazed off in other, more interesting directions. I’d met

women like her many times before. “My name’s Prudence,” she said.

“Of course it is,” I said.

“You really ought to join.”

“You know I’m not going to.”

She did know, too, and smiled a wide, long smile.

“But I’ll be here all night,” I said.

She settled back into her pool.

I lit a cigarette; for a moment, a flame cupped in my hand; I drew my hand away, and looked up to the peak. A man, briefly illuminated by moonlight before the clouds closed up, appeared at the top, moved toward the house. I said to Richard, “Does someone live up there?” Richard told me he didn’t think so. I tried to point out the man—who I could still see, as a dark shape on a dark background—but Richard couldn’t find him. “I’m going to go in, get a real drink,” I said. Richard said he’d be in shortly. I shrugged and walked around to the front of the house—an eye on the man walking down the mountain.

Most of the people at Richard’s party weren’t attractive. They might be fit and many were dressed in expensive clothes, but most of his friends looked average and, upon getting to know them, were. The exceptions were notable. Michael, a transplant from the coast, a man of style; Kat and Carmilla—just beautiful; Prudence—a manipulator I appreciated; and Sarah. Kat and Carmilla were seated on a small couch in the guest room, surrounded by four or five guys and one unfortunate looking girl (pasty, a large, flat nose and hair forced into a strange shade of red). They were all watching a movie—Kat spotted me in the doorway, shifted on the couch, shoved at one of the guys, and gestured for me to sit beside her. They were watching The Man Who Fell To Earth, that beautiful David Bowie film—

I let myself get drawn into the movie. Kat ran her hand in a circle on my back. When the unfortunate girl sneezed, breaking my mood, I excused myself and walked down the hall to the bar. I passed the front door just as there was a knock; the door was answered and I heard, “What, you need a formal invitation? Sure come on in, you are welcome to come in.” Sarah joined me at the bar and took my arm. We collected drinks and Michael and I went out onto the back patio. Mercifully, the three of us were there alone.

Sarah stole a cigarette and complained about Richard’s friends—”Present company excluded.”

Michael then brought up the subject Sarah and I had danced around once already: “What’s in Boston for you? I mean, I know Richard has a great job, but what are you going to do?”

Sarah looked at the floor for a moment, took a drag and a drink and said, “That’s just the thing, Michael.”

I was eager to hear her explain to Michael just what that thing was—I thought I knew but I wanted her to say it—but instead she stared past Michael, back into the house. I turned and Michael turned and we all watched a very ugly man walk past the back patio door toward the bar.

“Who the hell was that?” I asked.

Sarah said, “I don’t know, but—” then drifted past me into the hall. Michael and I looked at each other, then followed—I dropped my cigarette on the patio floor.

The ugly man wasn’t at the bar by the time we stepped into the hall—no one was.

He was in the living room, behind the piano, playing the adagio from the Moonlight Sonata on Richard’s out-of-tune grand—the result was not lulling or melancholic, as the adagio is, but dissonant and eerie.

No one else seemed to share my evaluation of the music. Everyone—the whole party except Prudence and her men—were gathered around the piano watching the ugly man play, laughing when he made an exaggerated flourish over the keyboard, but rapt, totally caught up—so that they all jumped when he moved into the more upbeat allegretto. I wanted to jump too—each out-of-tune note grated on my nerves.

I stared at the ugly man as he played. He was bald. His head was long and boney, his eyes lost in shadow. His skin was a dark brown—not like Michael’s, no, he didn’t look African—the ugly man was black all right, but his skin was waxy and all over there was a patina of green—the green of rotten beef. I couldn’t help but imagine what it would be like to touch his skin—my finger, I was sure, would sink in, as it would in a pool of congealed fat. His ears were large and pointed. His mouth was small—pursed as he played—and his teeth were too large for his tiny mouth. His two front teeth were the worst: jagged, yellow, buck-teeth.

I was greatly relieved to see that Sarah did not appear to be under his spell. She stood in the corner watching not the ugly man, but the crowd—and Richard, who stood with a stupid open-mouthed expression on his face, clapping like a little girl every time the ugly man crossed his hands over the keyboard. I could hear, barely audible, David Bowie’s voice in the guest room.

The ugly man stopped playing the piano then, and it dawned on me that he must be the man I’d seen coming down from the peak. He waved his hands in the air, and this seemed to release everyone. There was some applause, and people returned to what they had been doing. I watched Kat and Carmilla walk back toward the guest room, Michael made a bee-line for the bar, and Sarah and Richard walked over to me. I noticed the pasty girl with the bad dye-job standing next to the ugly man, looking down at him as he caressed her hand. The perfect couple, I thought. I led Sarah and Richard to the bar and insisted that Michael open the whisky I’d brought—a far better whisky than what he’d served me when I’d arrived.

I asked who the ugly man was.

Sarah said she didn’t know. Michael and Richard acted as if I hadn’t asked the question. I put my hand on Richard’s arm and asked again, and he said, “Which ugly man?”

I took Richard’s response to be a joke and gave him a forced, weak chuckle. My whisky was a relief. I needed a moment alone with Sarah—I wanted her to have a chance to finish what she’d been saying earlier, I wanted her to tell me that there was nothing for her in Boston, that she had no intention of ever joining Richard in Boston and was only pretending so as not to break his heart before his big trip.

I felt a hand on my shoulder. I was certain it was the ugly man’s; I was surprised—relieved—that the hand belonged to Prudence. “I’m out of the tub,” she whispered.

Sarah and Richard were talking; I asked Prudence what she wanted to drink and she held up a beer. “I’m all set in that department. Did you know they’re watching a movie in the guest room?”

“Yes,” I said. I followed Prudence down the hall. She’d put on a dress over her wet suit—somehow, with the bands of wet, clingy material around her waist and her chest, she seemed more naked than she had before. I’d catch up with Sarah later, catch her when Richard was off chatting up one of his boring friends.

Prudence and I entered the room—The Man Who Fell to Earth was still on—had Bowie yet revealed his alien identity? Kat and Carmilla were on the couch, and to my satisfaction, Kat shot Prudence a nasty look and beckoned me to a spot beside her. Prudence, first in the guest room, took that spot. Small as her hips were, there was no more room left on the couch. When she saw this, she slid off the couch, onto the floor, and offered me the spot Kat had already offered. Regardless of the outcome of my conversation with Sarah, I knew I would not leave the party alone; I considered, even, the possibility that Prudence and Kat’s attentions would prove useful in gaining Sarah’s attention.

Kat stroked my hair; Prudence my leg. The other men in the room couldn’t help but glance away from the television to look first at the women, then at me, wishing themselves in my position.

Just before the movie ended—a sad, pale scene—I’d been lulled by all the petting—the ugly man, the man from the peak, walked past the guest room. I caught a glimpse of him, just as he walked out of sight. Except for Prudence, the people in the guest room left: the guys, Carmilla and Kat. Before I could dwell on this much, Prudence was on the couch beside me, hand on the inside of my thigh, mouth drifting toward my face. I knew that face, drifting sleepily, a drunk woman about to kiss me. I let her kiss me. We kissed. Her tongue darted in and out of my own mouth. Her open hand pressed against my erection. My hand on the

damp cloth covering her right breast, my hand on the damp cloth at the small of her back.

I broke off our kissing. I said, “Let’s get something more to drink.” Though she gave me a petulant look, I knew she would do as I asked and I thought—for a moment—this woman actually knows what I’m doing, understands, would have ended the kiss herself, shortly, if I hadn’t. In that moment I preferred Prudence to Sarah. The moment was fleeting.

The ugly man had been speaking—addressing the entire party, it seemed. When Prudence and I stepped into the living room, he waved his hand as he’d done before, and the crowd dispersed as it had before. Everyone left the room except for one person, one of the guys who’d been in the hot tub with Prudence—I watched her watch him talk to the ugly man and Prudence said, “I knew he was gay.” I wasn’t sure who she was referring to at first—I didn’t think the ugly man was gay—and then I realized who she meant.

“Who is that man?” I asked.

“I don’t know. I’ve been outside all night.”

“Didn’t you see him come down from the peak?”

“From the peak? There’s nothing up there. I’m going to get another drink.”

She left me. I lit a cigarette and went out onto the patio. Richard and Sarah were out there, though Richard was talking with one of his friends and Sarah was just standing around, looking bored. She brightened when she saw me. I gave her a cigarette.

“Why don’t we go outside a while,” Sarah said.

We left the enclosed patio. We heard voices, coming from the direction of the hot tub. We walked out into the dark yard, toward the woods.

“What was that guy talking about?” I asked.

“Which guy?”

“The ugly guy. They guy with the buck teeth.”

Sarah turned up a confused expression. When she pulled on her cigarette, her face was illuminated. She had, I thought, the most perfect face. Between her eyebrows, just above the bridge of her nose was a circular patch of skin very smooth and brighter white than the rest of her face. I wanted to put my fingertip on that spot. I did. She scrunched her face up and giggled, brushing my finger away.

Inferno

Inferno The Best of the Best Horror of the Year

The Best of the Best Horror of the Year When Things Get Dark

When Things Get Dark A Whisper of Blood

A Whisper of Blood Echoes

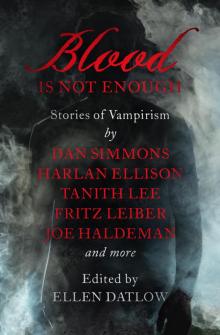

Echoes Blood Is Not Enough

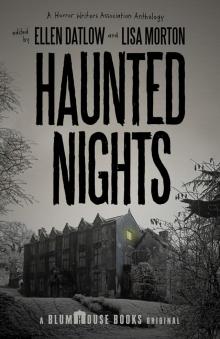

Blood Is Not Enough Haunted Nights

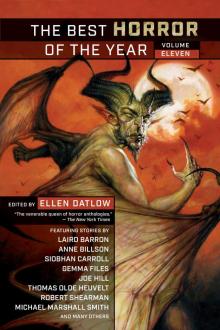

Haunted Nights The Best Horror of the Year Volume Eleven

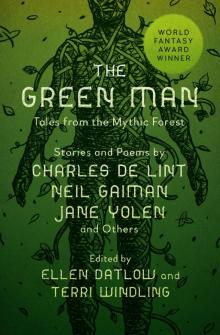

The Best Horror of the Year Volume Eleven The Green Man

The Green Man The Dark

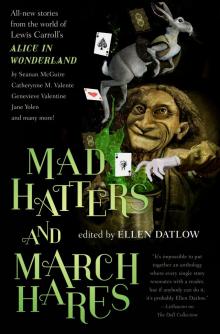

The Dark Mad Hatters and March Hares

Mad Hatters and March Hares Nebula Awards Showcase 2009

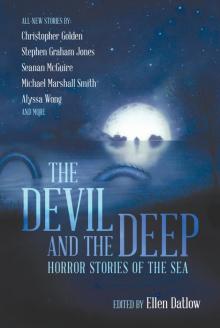

Nebula Awards Showcase 2009 The Devil and the Deep

The Devil and the Deep