- Home

- Ellen Datlow

The Best of the Best Horror of the Year Page 24

The Best of the Best Horror of the Year Read online

Page 24

“—and the time we lose smoothing things over with them completely fucks up Plowman’s schedule.”

“Stop worrying,” Buchanan said, but Vasquez was pleased to see his face blanch at the prospect of Plowman’s displeasure.

For a few moments, Vasquez leaned back in her chair and closed her eyes, the sun lighting the inside of her lids crimson. I’m here, she thought, the city’s presence a pressure at the base of her skull, not unlike what she’d felt patrolling the streets of Bagram, but less unpleasant. Buchanan said, “So you’ve been here before.”

“What?” Brightness overwhelmed her vision, simplified Buchanan to a dark silhouette in a baseball cap.

“You parlez the français pretty well. I figure you must’ve spent some time—what? In college? Some kind of study abroad deal?”

“Nope,” Vasquez said.

“‘Nope,’ what?”

“I’ve never been to Paris. Hell, before I enlisted, the farthest I’d ever been from home was the class trip to Washington senior year.”

“You’re shittin me.”

“Uh-uh. Don’t get me wrong: I wanted to see Paris, London—everything. But the money—the money wasn’t there. The closest I came to all this were the movies in Madame Antosca’s French 4 class. It was one of the reasons I joined up: I figured I’d see the world and let the Army pay for it.”

“How’d that work out for you?”

“We’re here, aren’t we?”

“Not because of the Army.”

“No, precisely because of the Army. Well,” she said, “them and the spooks.”

“You still think Mr.—oh, sorry—You-Know-Who was CIA?”

Frowning, Vasquez lowered her voice. “Who knows? I’m not even sure he was one of ours. That accent… he could’ve been working for the Brits, or the Aussies. He could’ve been Russian, back in town to settle a few scores. Wherever he picked up his pronunciation, dude was not regular military.”

“Be funny if he was on Stillwater’s payroll.”

“Hysterical,” Vasquez said. “What about you?”

“What about me?”

“I assume this is your first trip to Paris.”

“And there’s where you would be wrong.”

“Now you’re shittin me.”

“Why, because I ordered a cheeseburger and a Coke?”

“Among other things, yeah.”

“My senior class trip was a week in Paris and Amsterdam. In college, the end of my sophomore year, my parents took me to France for a month.” At what she knew must be the look on her face, Buchanan added, “It was an attempt at breaking up the relationship I was in at the time.”

“It’s not that. I’m trying to process the thought of you in college.”

“Wow, anyone ever tell you what a laugh riot you are?”

“Did it work—your parents’ plan?”

Buchanan shook his head. “The second I was back in the US, I knocked her up. We were married by the end of the summer.”

“How romantic.”

“Hey.” Buchanan shrugged.

“That why you enlisted, support your new family?”

“More or less. Heidi’s dad owned a bunch of McDonald’s; for the first six months of our marriage, I tried to assistant manage one of them.”

“With your people skills, that must have been a match made in Heaven.”

The retort forming on Buchanan’s lips was cut short by the reappearance of their waiter, encumbered with their drinks and their food. He set their plates before them with a, “Madame,” and, “M’sieu,” then, as he was distributing their drinks, said, “Everything is okay? Ça va?”

“Oui,” Vasquez said. “C’est bon. Merçi.”

With the slightest of bows, the waiter left them to their food.

While Buchanan worked his hands around his cheeseburger, Vasquez said, “I don’t think I realized you were married.”

“Were,” Buchanan said. “She wasn’t happy about my deploying in the first place, and when the shit hit the fan…” He bit into the burger. Through a mouthful of bun and meat, he said, “The court martial was the excuse she needed. Couldn’t handle the shame, she said. The humiliation of being married to one of the guards who’d tortured an innocent man to death. What kind of role model would I be for our son?

“I tried—I tried to tell her it wasn’t like that. It wasn’t that—you know what I’m talking about.”

Vasquez studied her neatly-folded crêpe. “Yeah.” Mr. White had favored a flint knife for what he called the delicate work.

“If that’s what she wants, fine, fuck her. But she made it so I can’t see my son. The second she decided we were splitting up, there was her dad with money for a lawyer. I get a call from this asshole—this is right in the middle of the court martial—and he tells me Heidi’s filing for divorce—no surprise—and they’re going to make it easy for me: no alimony, no child support, nothing. The only catch is, I have to sign away all my rights to Sam. If I don’t, they’re fully prepared to go to court, and how do I like my chances in front of a judge? What choice did I have?”

Vasquez tasted her coffee. She saw her mother, holding open the front door for her, unable to meet her eyes.

“Bad enough about that poor bastard who died—what was his name? If there’s one thing you’d think I’d know…”

“Mahbub Ali,” Vasquez said. What kind of a person are you? her father had shouted. What kind of person is part of such things?

“Mahbub Ali,” Buchanan said. “Bad enough what happened to him; I just wish I’d know what was happening to the rest of us, as well.”

They ate the rest of their meal in silence. When the waiter returned to ask if they wanted dessert, they declined.

II

Vasquez had compiled a list of reasons for crossing the Avenue and walking to the Eiffel Tower, from, It’s an open, crowded space: it’s a better place to review the plan’s details, to, I want to see the fucking Eiffel Tower once before I die, okay? But Buchanan agreed to her proposal without argument; nor did he complain about the fifteen euros she spent on a pair of sunglasses on the walk there. Did she need to ask to know he was back in the concrete room they’d called the Closet, its air full of the stink of fear and piss?

Herself, she was doing her best not to think about the chamber under the prison’s sub-basement Just-Call-Me-Bill had taken her to. This was maybe a week after the tall, portly man she knew for a fact was CIA had started spending every waking moment with Mr. White. Vasquez had followed Bill down poured concrete stairs that led from the labyrinth of the basement and its handful of high-value captives in their scattered cells (not to mention the Closet, whose precise location she’d been unable to fix), to the sub-basement, where he had clicked on the large yellow flashlight he was carrying. Its beam had ranged over brick walls, an assortment of junk (some of it Soviet-era aircraft parts, some of it tools to repair those parts, some of it more recent: stacks of toilet paper, boxes of plastic cutlery, a pair of hospital gurneys). They had made their way through that place to a low doorway that opened on carved stone steps whose curved surfaces testified to the passage of generations of feet. All the time, Just-Call-Me-Bill had been talking, lecturing, detailing the history of the prison, from its time as a repair center for the aircraft the Soviets flew in and out of here, until some KGB officer decided the building was perfect for housing prisoners, a change everyone who subsequently held possession of it had maintained. Vasquez had struggled to pay attention, especially as they had descended the last set of stairs and the air grew warm, moist, the rock to either side of her damp. Before, the CIA operative was saying, oh, before. Did you know a detachment of Alexander the Great’s army stopped here? One man returned.

The stairs had ended in a wide, circular area. The roof was flat, low, the walls no more than shadowy suggestions. Just-Call-Me-Bill’s flashlight had roamed the floor, picked out a symbol incised in the rock at their feet: a rough circle, the diameter of a manhole cover, broken

at about eight o’clock. Its circumference was stained black, its interior a map of dark brown splotches. Hold this, he had said, passing her the flashlight, which had occupied her for the two or three seconds it took him to remove a plastic baggie from one of the pockets of his safari vest. When Vasquez had directed the light at him, he was dumping the bag’s contents in his right hand, tugging at the plastic with his left to pull it away from the dull red wad. The stink of blood and meat on the turn had made her step back. Steady, specialist. The bag’s contents had landed inside the broken circle with a heavy, wet smack. Vasquez had done her best not to study it too closely.

A sound, the scrape of bare flesh dragging over stone, from behind and to her left, had spun Vasquez around, the flashlight held out to blind, her sidearm freed and following the light’s path. This section of the curving wall opened in a black arch like the top of an enormous throat. For a moment, that space had been full of a great, pale figure. Vasquez had had a confused impression of hands large as tires grasping either side of the arch, a boulder of a head, its mouth gaping amidst a frenzy of beard, its eyes vast, idiot. It was scrambling towards her; she didn’t know where to aim—

And then Mr. White had been standing in the archway, dressed in the white linen suit that somehow always seemed stained, even though no discoloration was visible on any of it. He had not blinked at the flashlight beam stabbing his face; nor had he appeared to judge Vasquez’s gun pointing at him of much concern. Muttering an apology, Vasquez had lowered gun and light immediately. Mr. White had ignored her, strolling across the round chamber to the foot of the stairs, which he had climbed quickly. Just-Call-Me-Bill had hurried after, a look on his bland face that Vasquez took for amusement. She had brought up the rear, sweeping the flashlight over the floor as she reached the lowest step. The broken circle had been empty, except for a red smear that shone in the light.

That she had momentarily hallucinated, Vasquez had not once doubted. Things with Mr. White already had raced past what even Just-Call-Me-Bill had shown them, and however effective his methods, Vasquez was afraid that she—that all of them had finally gone too far, crossed over into truly bad territory. Combined with a mild claustrophobia, that had caused her to fill the dark space with a nightmare. However reasonable that explanation, the shape with which her mind had replaced Mr. White had plagued her. Had she seen the Devil stepping forward on his goat’s feet, one red hand using his pitchfork to balance himself, it would have made more sense than that giant form. It was as if her subconscious was telling her more about Mr. White than she understood. Prior to that trip, Vasquez had not been at ease around the man who never seemed to speak so much as to have spoken, so that you knew what he’d said even though you couldn’t remember hearing him saying it. After, she gave him still-wider berth.

Ahead, the Eiffel Tower swept up into the sky. Vasquez had seen it from a distance, at different points along hers and Buchanan’s journey from their hotel towards the Seine, but the closer she drew to it, the less real it seemed. It was as if the very solidity of the beams and girders weaving together were evidence of their falseness. I am seeing the Eiffel Tower, she told herself. I am actually looking at the goddamn Eiffel Tower.

“Here you are,” Buchanan said. “Happy?”

“Something like that.”

The great square under the Tower was full of tourists, from the sound of it, the majority of them groups of Americans and Italians. Nervous men wearing untucked shirts over their jeans flitted from group to group—street vendors, Vasquez realized, each one carrying an oversized ring strung with metal replicas of the Tower. A pair of gendarmes, their hands draped over the machine guns slung high on their chests, let their eyes roam the crowd while they carried on a conversation. In front of each of the Tower’s legs, lines of people waiting for the chance to ascend it doubled and redoubled back on themselves, enormous fans misting water over them. Taking Buchanan’s arm, Vasquez steered them towards the nearest fan. Eyebrows raised, he tilted his head towards her.

“Ambient noise,” she said.

“Whatever.”

Once they were close enough to the fan’s propeller drone, Vasquez leaned into Buchanan. “Go with this,” she said.

“You’re the boss.” Buchanan gazed up, a man debating whether he wanted to climb that high.

“I’ve been thinking,” Vasquez said. “Plowman’s plan’s shit.”

“Oh?” He pointed at the Tower’s first level, three hundred feet above.

Nodding, Vasquez said, “We approach Mr. White, and he’s just going to agree to come with us to the elevator.”

Buchanan dropped his hand. “Well, we do have our… persuaders. How do you like that? Was it cryptic enough? Or should I have said, ‘Guns’?”

Vasquez smiled as if Buchanan had uttered an endearing remark. “You really think Mr. White is going to be impressed by a pair of .22s?”

“A bullet’s a bullet. Besides,” Buchanan returned her smile, “isn’t the plan for us not to have to use the guns? Aren’t we relying on him remembering us?”

“It’s not like we were BFFs. If it were me, and I wanted the guy, and I had access to Stillwater’s resources, I wouldn’t be wasting my time on a couple of convicted criminals. I’d put together a team and go get him. Besides, twenty grand a piece for catching up to someone outside his hotel room, passing a couple of words with him, then escorting him to an elevator: tell me that doesn’t sound too good to be true.”

“You know the way these big companies work: they’re all about throwing money around. Your problem is, you’re still thinking like a soldier.”

“Even so, why spend it on us?”

“Maybe Plowman feels bad about everything. Maybe this is his way of making it up to us.”

“Plowman? Seriously?”

Buchanan shook his head. “This isn’t that complicated.”

Vasquez closed her eyes. “Humor me.” She leaned her head against Buchanan’s chest.

“What have I been doing?”

“We’re a feint. While we’re distracting Mr. White, Plowman’s up to something else.”

“Like?”

“Maybe Mr. White has something in his room; maybe we’re occupying him while Plowman’s retrieving it.”

“You know there are easier ways for Plowman to steal something.”

“Maybe we’re keeping Mr. White in place so Plowman can pull a hit on him.”

“Again, there are simpler ways to do that that would have nothing to do with us. You knock on the guy’s door, he opens it, pow.”

“What if we’re supposed to get caught in the crossfire?”

“You bring us all the way here just to kill us?”

“Didn’t you say big companies like to spend money?”

“But why take us out in the first place?”

Vasquez raised her head and opened her eyes. “How many of the people who knew Mr. White are still in circulation?”

“There’s Just-Call-Me-Bill—”

“You think. He’s CIA. We don’t know what happened to him.”

“Okay. There’s you, me, Plowman—”

“Go on.”

Buchanan paused, reviewing, Vasquez knew, the fates of the three other guards who’d assisted Mr. White with his work in the Closet. Long before news had broken about Mahbub Ali’s death, Lavalle had sat on the edge of his bunk, placed his gun in his mouth, and squeezed the trigger. Then, when the shitstorm had started, Maxwell, on patrol, had been stabbed in the neck by an insurgent who’d targeted only him. Finally, in the holding cell awaiting his court martial, Ruiz had taken advantage of a lapse in his jailers’ attention to strip off his pants, twist them into a rope, and hang himself from the top bunk of his cell’s bunkbed. His guards had cut him down in time to save his life, but Ruiz had deprived his brain of oxygen for sufficient time to leave him a vegetable. When Buchanan spoke, he said, “Coincidence.”

“Or conspiracy.”

“Goddammit.” Buchanan pulled free of Vasquez,

and headed for the long, rectangular park that stretched behind the Tower, speedwalking. His legs were sufficiently long that she had to jog to catch up to him. Buchanan did not slacken his pace, continuing his straight line up the middle of the park, through the midst of bemused picnickers. “Jesus Christ,” Vasquez called, “will you slow down?”

He would not. Heedless of oncoming traffic, Buchanan led her across a pair of roads that traversed the park. Horns blaring, tires screaming, cars swerved around them. At this rate, Vasquez thought, Plowman’s motives won’t matter. Once they were safely on the grass again, she sped up until she was beside him, then reached high on the underside of Buchanan’s right arm, not far from the armpit, and pinched as hard as she could.

“Ow! Shit!” Yanking his arm up and away, Buchanan stopped. Rubbing his skin, he said, “What the hell, Vasquez?”

“What the hell are you doing?”

“Walking. What did it look like?”

“Running away.”

“Fuck you.”

“Fuck you, you candy-ass pussy.”

Buchanan’s eyes flared.

“I’m trying to work this shit out so we can stay alive. You’re so concerned about seeing your son, maybe you’d want to help me.”

“Why are you doing this?” Buchanan said. “Why are you fucking with my head? Why are you trying to fuck this up?”

“I’m—”

“There’s nothing to work out. We’ve got a job to do; we do it; we get the rest of our money. We do the job well, there’s a chance Stillwater’ll add us to their payroll. That happens—I’m making that kind of money—I hire myself a pit bull of a lawyer and sic him on fucking Heidi. You want to live in goddamn Paris, you can eat a croissant for breakfast every morning.”

“You honestly believe that.”

“Yes I do.”

Vasquez held his gaze, but who was she kidding? She could count on one finger the number of stare-downs she’d won. Her arms, legs, everything felt suddenly, incredibly heavy. She looked at her watch. “Come on,” she said, starting in the direction of the Avenue de la Bourdonnais. “We can catch a cab.”

Inferno

Inferno The Best of the Best Horror of the Year

The Best of the Best Horror of the Year When Things Get Dark

When Things Get Dark A Whisper of Blood

A Whisper of Blood Echoes

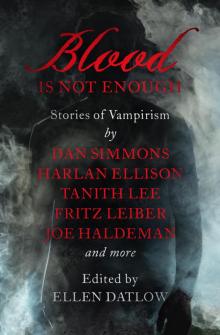

Echoes Blood Is Not Enough

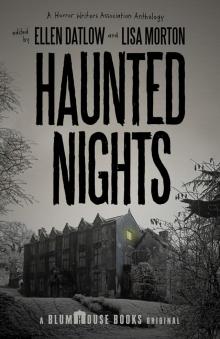

Blood Is Not Enough Haunted Nights

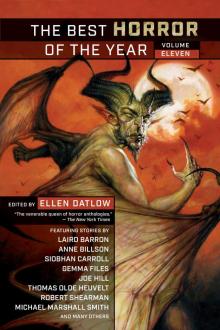

Haunted Nights The Best Horror of the Year Volume Eleven

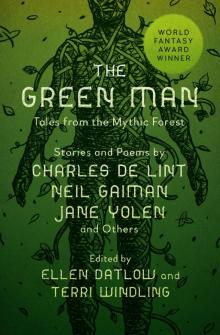

The Best Horror of the Year Volume Eleven The Green Man

The Green Man The Dark

The Dark Mad Hatters and March Hares

Mad Hatters and March Hares Nebula Awards Showcase 2009

Nebula Awards Showcase 2009 The Devil and the Deep

The Devil and the Deep