- Home

- Ellen Datlow

A Whisper of Blood Page 3

A Whisper of Blood Read online

Page 3

Rose hung back, timid and confused now that her moment had come. After all, did she really want her grandchild’s presumably fond memories of Gramma Rose replaced with the memory of Rose the vampire?

Stephanie said, “I won’t go until you come talk to me, Gramma Rose.”

She curled up on Rose’s empty bed and went to sleep.

Rose watched her dreams winking and wiggling in her aura. Such an appealing mixture of cynicism and naivete, so unlike her mother. Fascinated, Rose observed from the ceiling where she floated.

Involuntarily reacting to one of the little scenes, she murmured, “It’s not worth fighting with your mother; just say yes and go do what you want.”

Stephanie opened her eyes and looked directly up. Her jaw dropped. “Gramma Rose,” she squeaked. “I see you! What are you doing up there?”

“Stephanie darling,” Rose said in the weak, rusty voice that was all she could produce now, “you can help me. Will you help me?”

“Sure,” Stephanie said, sitting up. “Didn’t you stop me from making an utter idiot of myself with Jeff Stanhope, which isn’t his real name of course, and he has a gossip drive on him that just won’t quit. I don’t know what I was thinking of, bringing him up here, except that he’s cute of course, but actors are mostly cute. It’s his voice, I think, it’s sort of hypnotic. But you woke me up, just like they say, a still, small voice. So what can I do for you?”

“This will sound a little funny,” Rose said anxiously—to have hope again was almost more than she could bear—“but could you stand up in the bed and let me try to drink a little blood from your neck?”

“Ew.” Stephanie stared up at her. “You’re kidding.”

Rose said, “It’s either that or I’m gone, darling. I’m nearly gone as it is.”

“But why would it help to, ugh, suck a person’s blood?”

“I need it to weigh me down, Stephanie. You can see how high I’m drifting. If I don’t get some blood to anchor me, I’ll float away.”

“How much do you need?” Stephanie said cautiously.

“From you, darling, just a little,” Rose assured her. “You have a rehearsal in the morning, I don’t want to wear you out. But if you let me take a little, I can stay, I can talk to you.”

“You could tell me all about Uncle Herb and whether he was gay or not,” Stephanie said, “and whether Great-Grandpa really left Hungary because of a quarrel with a hussar or was he just dodging the draft like everybody else—all the family secrets.”

Rose wasn’t sure she remembered those things, but she could make up something appropriate. “Yes, sure.”

“Is this going to hurt?” Stephanie said, getting up on her knees in the middle of the mattress.

“It doesn’t when they do it in the movies,” Rose said. “But, Stephanie, even if there’s a little pinprick, wouldn’t that be all right? Otherwise I have to go, and, and I don’t want to.”

“Don’t cry, Gramma Rose,” Stephanie said. “Can you reach?” She leaned to one side and shut her eyes.

Rose put her wavery astral lips to the girl’s pale skin, thinking, FANGS. As she gathered her strength to bite down, a warm sweetness flowed into her mouth like rich broth pouring from a bowl. She stopped almost at once for fear of overdoing it.

“That’s nice,” Stephanie murmured. “Like a toke of really good grass.”

Rose, flooded with weight and substance that made her feel positively bloated after her recent starvation, put her arm around Stephanie’s shoulders and hugged her. “Just grass,” she said, “right? You don’t want to poison your poor old dead gramma.”

Stephanie giggled and snuggled down in the bed. Rose lay beside her, holding her lightly in her astral arms and whispering stories and advice into Stephanie’s ear. From time to time she sipped a little blood, just for the thrill of feeling it sink through her newly solid form, anchoring it firmly to her own familiar bed.

Stephanie left in the morning, but she returned the next day with good news. While the lawyers and the building owners and the relatives quarreled over the fate of the apartment and everything in it (including the ghost that Bill the super wouldn’t shut up about), Stephanie would be allowed to move in and act as caretaker.

She brought little with her (an actress has to learn to travel light, she told Rose), except her friends. She would show them around the apartment while she told them how the family was fighting over it, and how it was haunted, which made everything more complicated and more interesting, of course. Rose herself was never required to put in a corroborating appearance. Stephanie’s delicacy about this surprised and pleased Rose.

Still, she preferred the times when Stephanie stayed home alone studying her current script, which she would declaim before the full-length mirror in the bedroom. She was a terrible show-off, but Rose supposed you had to be like that to be on the stage.

Rose’s comments were always solicited, whether she was visible or not. And she always had a sip of blood at bedtime.

Of course this couldn’t go on forever, Rose understood that. For one thing, at the outer edges of Stephanie’s aura of thoughts and dreams she could see images of a different life, somewhere cool and foggy and hemmed in with dark trees, or city streets with a vaguely foreign look to them. She became aware that these outer images were of likely futures that Stephanie’s life was moving toward. They didn’t seem to involve staying at Rose’s.

She knew she should be going out to cultivate alternative sources for the future—vampires could “live” forever, couldn’t they—but she didn’t like to leave in case she couldn’t get back for some reason, like running water, crosses, or garlic.

Besides, her greatest pleasure was coming to be that of floating invisibly in the air, whispering advice to Stephanie based on foresight drawn from the flickering images she saw around the girl:

“It’s not a good part for you, too screechy and wild. You’d hate it.”

“That one is really ambitious, not just looking for thrills with pretty actresses.”

“No, darling, she’s trying to make you look bad—you know you look terrible in yellow.”

Rose became fascinated by the spectacle of her granddaughter’s life shaping itself, decision by decision, before her astral eyes. So that was how a life was made, so that was how it happened! Each decision altered the whole mantle of possibilities and created new chains of potentialities, scenes and sequences that flickered and fluttered in and out of probability until they died or were drawn in to the center to become the past.

There was a young man, another one, who came home with Stephanie one night, and then another night. Rose, who drowsed through the days now because there was nothing interesting going on, attended eagerly, and invisibly, on events. The third night Rose whispered, “Go ahead, darling, it wouldn’t be bad. Try the Chinese rug.”

They tumbled into the bed after all; too bad. The under rug should be used for something significant, it had cost her almost as much per yard as the carpet itself.

Other people’s loving looked odd. Rose was at first embarrassed and then fascinated and then bored: bump bump bump, squeeze, sigh, had she really done that with Fred? Well, yes, but it seemed very long ago and sadly meaningless. The person with whom it had been worth all the fuss had been—whatsisname, it hovered just beyond memory.

Fretful, she drifted up onto the roof. The clouds were there, the massive form turned toward her now. She cringed but held her ground. No sign from above one way or the other, which was fine with her.

The Angel chimed, “How are you, Rose?”

Rose said, “So what’s the story, Simkin? Have you come to reel me in once and for all?”

“Would you mind very much if I did?”

Rose laughed at the Angel’s transparent feet, its high, delicate arches. She was keenly aware of the waiting form of the cloud-giant, but something had changed.

“Yes,” she said, “but not so much. Stephanie has to learn to judge things for herself. Also,

if she’s making love with a boy in the bedroom knowing I’m around, maybe she’s taking me a little for granted. Maybe she’s even bored by the whole thing.”

“Or maybe you are,” the Angel said.

“Well, it’s her life,” Rose said, feeling as if she were breaking the surface of the water after a deep dive, “not mine.”

The Angel said, “I’m glad to hear you say that. This was never intended to be a permanent solution.”

As it spoke, a great throb of anxiety and anger reached Rose from Stephanie.

“Excuse me,” she said, and she dropped like a plummet back to her apartment.

The two young people were sitting up in bed facing each other with the table lamp on. The air vibrated with an anguish connected with the telephone on the bed table. In the images dancing in Stephanie’s aura Rose read the immediate past: There had been a call for the boy, a screaming voice raw with someone else’s fury. He had just explained to Stephanie, with great effort and in terror that she would turn away from him. The girl was indeed filled with dismay and resentment. She couldn’t accept this dark aspect of his life because it had all looked so bright to her before, for both of them.

Avoiding her eyes, he said bitterly, “I know it’s a mess. You have every right to kick me out before you get any more involved.”

Rose saw the pictures in his aura, some of them concerned with his young sister who went in and out of institutions and, calamitously, in and out of his life. But many showed this boy holding Stephanie’s hand, holding Stephanie, applauding Stephanie from an audience, sitting with Stephanie on the porch of a wooden house amid dark, tall trees somewhere—

Rose looked at Stephanie’s aura. This boy was all over it. Invisible, Rose whispered in Stephanie’s ear, “Stick with him, darling, he loves you and it looks like you love him, too.”

At the same moment she heard a faint echo of very similar words in Stephanie’s mind. The girl looked startled, as if she had heard this, too.

“What?” the boy said, gazing at her with anxious intensity.

Stephanie said, “Stay in my life. I’ll try to stay in yours.”

They hugged each other. The boy murmured into her neck, where Rose was accustomed to take her nourishment, “I was so afraid you’d say no, go away and take your problems with you—”

Seeing the shine of tears in the boy’s eyes, Rose felt the remembered sensation of tears in her own. As she watched, their auras slowly wove together, flickering and bleeding colors into each other. This seemed so much more intimate than sex that Rose felt she really ought to leave the two of them alone.

The Angel was still on the roof, or almost on it, hovering above the parapet.

Rose said, “She doesn’t need me anymore; she can tell herself what to do as well as I can, probably better.”

“If she’ll listen,” the Angel said.

Rose looked down at the moving lights of cars on the street below. “All right,” she said. “I’m ready. How do I get rid of the blood I got from Stephanie this morning?”

“You mean this?"The Angel’s finger touched Rose’s chest, where a warm red glow beat in the place where her heart would have been. “I can get rid of it for you, but I warn you, it’ll hurt.”

“Do it,” Rose said, powered by a surging impatience to get on with something of her own for a change, having been so immersed in Stephanie’s raw young life—however long it was now. Time was much harder to divide intelligibly than it had been.

The Angel’s finger tapped once, harder, and stabbed itself burningly into her breast. There came a swift sensation of what it must feel like to have all the marrow drawn at once from your bones. Rose screamed.

She opened her eyes and looked down, gasping, at the Angel. Already she was rising like some light, vaned seed on the wind. She saw the Angel point downward at the roof with one glowing, crimson finger. One flick and a stream of bright fire shot down through the shadowy outline of the building and landed—she saw it happen, the borders of her vision were rushing away from her in all directions—in the kitchen sink and ran away down the drain.

Stephanie turned her head slightly and murmured, “What was that? I heard something.”

The boy kissed her temple. “Nothing.” He gathered her closer and rolled himself on top of her, nuzzling her. What an appetite they had, how exhausting!

Other voices wove in and out of their murmuring voices. Rose could see and hear the whole city as it slowly sank away below her, a net of lights slung over the dark earth.

But above her—and she no longer needed to direct her vision to see what was there but saw directly with her mind’s eye—the sky was thick with a massed and threatening darkness that she knew to be God: still waiting, scowling, implacable, for His delayed confrontation with Rose.

Despite the panic pulsating through her as the inevitable approached, she couldn’t help noticing that there was something funny about God. The closer she got, the more His form blurred and changed, so that she caught glimpses of tiny figures moving, colors surging, skeins of ceaseless activity going on all at once and overlapping inside the enormous cloudy bulk of God.

She recognized the moving figures: Papa Sol, teasing her at the breakfast table by telling her to look, quick, at the horse on the windowsill, and grabbing one of the strawberries from her cereal while she looked with eager, little-girl credulity; Roberta, crying and crying in her crib while grown-up Rose hovered in the hallway torn between exhaustion and rage and love and fear of doing the wrong thing no matter what she did; Fred, sparkling with lying promises he’d never meant to keep, but pleased to entertain her with them; Stephanie, with crooked braids and scabby knees, counting the pennies from the penny jar that Rose had once kept for her. And that was the guy, there, Aleck Mills, one of Fred’s associates, with whom love had felt like love.

If she looked beyond these images, Rose realized that she could see, deeper in the maze, the next phase of each little scene, and the next, the whole spreading tangle of consequences that she was here to witness, to comprehend, and to judge.

The web of her awareness trembled as it soared, curling in on itself as if caught in a draught of roasting air.

“Simkin, where are you?” she cried.

“Here,” the Angel answered, bobbing up alongside of her and looking, for once, a bit flustered with the effort of keeping up. “And you don’t need me anymore. Guardian angels don’t need guardian angels.”

“Now I lay me down to sleep,” Rose said, remembering that saccharine Humperdinck opera she had taken Stephanie to once at Christmas time, years ago, because it was supposed to be for kids. “A bunch of vampires watch do keep?”

“You could put it that way,” the Angel said.

“What about Dracula?” Rose said. “Could I have done that instead?”

“Sure,” the Angel said. “There’s always a choice. Who do you think it is who goes around making deals for the illusion of immortal life? And the price isn’t anything as romantic as your soul. It’s just a little blood, for as long as you’re willing.”

“And when you stop being willing?”

The Angel flashed its blank eyes upward. “Your life will wait as long as it has to.”

“I’m scared of my life,” Rose confessed. “I’m scared there’s nothing worthwhile in it, nothing but furniture, and statuettes made into lamps.” “Kid,” the Angel said, “you should have seen mine.” “Yours?”

“Full of people I tried to make into furniture, all safe and comfortable, with lots of dust cuzzies stuck underneath.”

“What’s in mine?” Rose said.

“Go and see,” the Angel said gently.

“I am, I’m going,” Rose said. In her heart she moaned, This will be hard, this is going to be so hard.

But she was heartened by a little scene flickering high up where God’s eye would have been if there had been a god instead of this mountain of Rose’s own life, and in that scene Stephanie and the boy did walk together on a winter beach.

By the way they hugged and turned up their collars and hurried along, it was cold and windy there; but they kept close together and made blue-lipped jokes about the cold.

Beyond them, beyond the edges of the cloud-mountain itself, Rose could make out nothing yet. Perhaps there was nothing, just as Papa Sol had promised. On the other hand, she thought, whirling aloft, so far Papa Sol had been 100 percent dead wrong.

I never expected to write another vampire story after The Vampire Tapestry, but Ellen said, “C’mon, c’mon,” and after a while something started (as a story about people walking their dogs, actually, but that’s one reason I am so slow to produce work—everything starts somewhere else and the real story has to be teased out into the light). And pretty soon I was working on the old bloodsucker concept with a different perspective than that which produced Dr. Weyland, my 1980 model of the beast.

For one thing, I’m fifty years old and more inclined than I was to contemplate last things. Also, like many of my generation I have numerous elderly relatives, most of them (though not all) female, most of them living alone; so maybe it’s not at all surprising that this story became Rose’s story. I’m glad it did.

And then, too, the more clearly one recognizes that what’s frightening about life in the world is the destructive flailings of people’s fears, and the more sophisticated those fears become in a sophisticated age, the more quaintly baroque become such fusty old creatures of superstition as vampires; and one’s approach alters accordingly.

On the other hand (not for nothing am I a Libra), I recently did a collaboration with Quinn Yarbro for the purposes of which I woke up Weyland. Now he won’t lie down again, and he is a bit light in the quaint and endearing department. So who knows what coloring my next outing into this territory may take (if indeed there is a next outing that is fit to see print)? That’s the nice thing about the career of making up stories—you can always change your mind and tell it the other way next time.

Suzy McKee Charnas

THE SLUG

Inferno

Inferno The Best of the Best Horror of the Year

The Best of the Best Horror of the Year When Things Get Dark

When Things Get Dark A Whisper of Blood

A Whisper of Blood Echoes

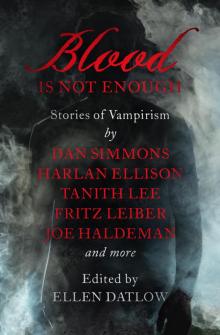

Echoes Blood Is Not Enough

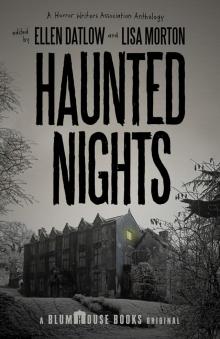

Blood Is Not Enough Haunted Nights

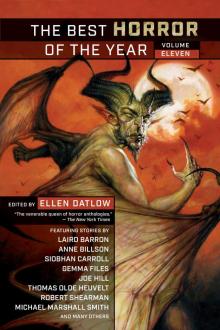

Haunted Nights The Best Horror of the Year Volume Eleven

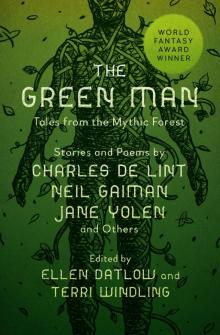

The Best Horror of the Year Volume Eleven The Green Man

The Green Man The Dark

The Dark Mad Hatters and March Hares

Mad Hatters and March Hares Nebula Awards Showcase 2009

Nebula Awards Showcase 2009 The Devil and the Deep

The Devil and the Deep