- Home

- Ellen Datlow

When Things Get Dark Page 3

When Things Get Dark Read online

Page 3

About halfway down the road someone from out of state had bought a huge parcel of the lakefront, where for the last ten years they’d been building a vast compound. We both knew some of the contractors who’d worked there at some point—stonemasons, builders, roofers, electricians, plumbers, heating and cooling experts, carpenters—and they told us what was inside the various Shingle-style mansions and outbuildings that had been erected. An indoor swimming pool, a billiards room, a separate building devoted to a screening room with a bar designed to look like an English pub. A miniature golf course with bronze statues at every hole. The caretaker had his own Craftsman cottage, bigger than my house.

Most extravagant of all was an outdoor carousel housed in its own building. Electronically controlled curtains kept us from ever being able to see what this looked like inside. There was also a hideous, two-story high, blaze-orange cast-resin sculpture of a plastic duck. In nearly a decade, we never saw any sign that someone had occupied the house or property, other than the caretaker.

One winter day early in the construction, when the mansion had been closed in and roofed but none of the interior work had been done, Rose and I halted to stare up at it. Work had stopped for the winter.

“That is a disgusting waste of money,” I said.

“You’re not kidding. They’re heating it, too.”

“Heating it? The windows aren’t even in.”

“I know. But the heat’s blasting inside.”

“How do you know?”

“Cause I’ve been in a bunch of times. The doors are all open. Want to see?”

I glanced down the road, toward the caretaker’s house. A thick stand of evergreens screened us from it. Besides, if anyone caught us, what would they do? We were two respectable middle-aged ladies who’d served on town committees and contributed to dozens of bake sales.

“Sure,” I said, and we went inside.

It was warm as a hotel room in there. Tens of thousands of dollars’ worth of tools and materials had been left in the various rooms— electrical wiring, sheetrock, tools, shopvacs, you name it. We wandered around for a while, but I lost interest fairly quickly. There were no furnishings, and the lake view was nice but not spectacular. I also wondered if the owners had installed some kind of security system.

“We better go,” I said. “They might have CCTV or something.”

Rose shrugged. “Yeah, okay. But it’s fun, isn’t it?”

“Yeah,” I said, and we returned to the road. After few seconds I added, “I used to do that sometimes, on the camp roads. Go into houses when no one was there.”

“No!” Rose exclaimed so loudly that at first I thought she was horrified. “Me too! For years.”

“Really?”

“Sure. No one ever used to lock their doors. It was fun. I never did anything.”

“Me neither.”

After that, we’d compare notes whenever we passed a house we had entered. Rose knew more about the owners than I did, but then she knew more people in town than me. Sometimes, when Helen walked with us, we’d forget and mention a camp we’d both been inside.

“How do you know these people?” Helen asked me.

“I don’t,” I said. “I just like looking in their windows.”

“Me too,” said Rose.

Last October, the three of us took a long afternoon walk, not on one of the camp roads but a sparsely populated paved road that runs from our village center up the neighboring mountainside. We call it Mount Kilden; it’s actually a hill. We drove in my car to where there’s a pull-out and parked, then started to walk. Helen with her long legs strode a good ten feet in front of Rose and me, and looked over her shoulder to shout her contributions to our conversation.

“If you want to talk you’re going to have to slow down,” I finally yelled.

Helen halted, shaking her head. “You both should walk with Tim— I have to run to keep up with him.”

I said, “If I ran I’d have a heart attack.”

Helen laughed. “Good thing I know CPR,” she said, and once more started walking like she was in a race.

The paved road up Mount Kilden runs for about four miles, then does a dogleg and turns into an old gravel road that continues for another mile or two before it ends abruptly in a pull-out surrounded by towering pines. A rough trail ran from the pull-out to the top of Mount Kilden, with a spectacular view of the lakes, Agganangatt River, and the real mountains to the north. The trail was used by locals who made a point of not telling people from away about it. It had been a decade since I’d walked that path.

A hundred and fifty years ago, most of this was farmland, including a blueberry barren. Now woodland has overtaken the fields: tall maples and oaks, birch and beech, white pine, hemlock, impassable thorny blackberry vines. The autumn leaves were at their peak, gold and scarlet and yellow against a sky so blue it made my eyes hurt. Goldenrod and aster and Queen Anne’s lace bloomed along the side of the road. Somewhere far away a dog barked, but up here you couldn’t hear a single car. Our pace had slackened, and even Helen slowed to admire the trees.

“It’s so beautiful up here,” she said. “We should walk here more often. Why don’t we walk here more often?”

I groaned. “Maybe because I’d have a heart attack every time we did?”

“We can go back if you want,” said Rose, and patted my arm.

“No, I’m fine. I’ll just walk slowly.”

Within a few minutes, we all started to walk more slowly. The woods had retreated from the road here: we could see more sky, which gave the impression we were much higher than we really were. Old stone walls snaked among the trees, marking boundaries between farms and homesteads that had long since disappeared. Nothing remained of the houses except for cellar holes, and the trees that had been planted by their front doors—always a pair, one lilac and one apple tree, the lilacs now forming dense stands of grey and withered green, the apple trees still bearing fruit.

I picked one. It tasted sweet and slightly winey—a cider apple. I finished it and tossed the core into the woods, and hurried after the others.

“Look,” said Helen, pointing to where the trees thinned out ever more, just past a curve in the dirt road. “Don’t you love that house? When Tim and I used to hike up here, we always said we’d buy it and live there someday.”

“We did too!” exclaimed Rose in delight. “Hank loved that house. I loved that house.”

They both glanced at me, and I nodded. “I never came here with Brandon, but oh yes. It’s a beautiful house.”

Laughing, Rose broke into an almost-run. Helen followed and quickly passed her. After a minute or two, I caught up with them.

A broad lawn swept down to the road. The grass looked like it hadn’t been mowed in a few weeks, but it hadn’t been neglected to the point where weeds or saplings had taken root. Brilliant crimson leaves carpeted it, from an immense maple tree that towered in the middle of the lawn. Thirty or so feet behind the tree stood a house. Not an old farmhouse or Cape Cod, which you’d expect to find here, and not a Carpenter Gothic, either. This was a Federal-style house, almost square and two stories tall, with lots of big windows, white clapboard siding, and two brick chimneys. You don’t see a whole lot of Federal houses in this area, and I’d guess this one was built in the early 1800s. There was no sign of a barn or other outbuildings. No garage, though that’s not so unusual. We don’t have a garage, either. Blue and purple asters grew along its front walls, and the tall grey stalks of daylilies that had gone by.

The house appeared vacant—no curtains in the windows, no lights— but it had been kept up. The white paint was weathered but not too bad. The granite foundation hadn’t settled. The chimneys were intact and didn’t seem in need of repointing. I walked up to the front door and tried the knob.

It turned easily in my hand. I looked back to catch Rose’s eye, but she was heading around the side of the house. A moment later I heard her cry out.

“Marianne, look!”

/>

I left the door and walked to the side of the house, where Rose pointed at a sign leaning against the wall.

FOR SALE BY OWNER.

“It’s for sale,” she said, almost reverently.

“It was for sale.” Helen picked up the sign and hefted it—handmade of plywood painted white and nailed to a stake. “They probably took it off the market after Labor Day.”

I stepped closer to examine it. The words FOR SALE BY OWNER were neatly painted in black letters. Beneath, someone had scrawled a phone number in Magic Marker. The numbers had blurred together from the rain. I didn’t recognize the area code.

“I wonder what they’re asking for it,” said Helen, and leaned the sign back against the house.

“A lot,” I said. Real estate here has gone through the roof in the last ten years.

“Well, I don’t know.” Rose stepped back and stared up at the roofline, straight as though drawn by a ruler on the sky. “It’s kind of far from everything.”

“There is no ‘far from anything’ in this town,” I retorted. “And people who move here, they want privacy.”

“Then why hasn’t it sold?”

“If the owner’s selling it, it might not be listed anywhere. Nobody drives up here except locals. And the season’s over, it’s off the market now anyway. That’s why they took down the sign.” I gestured to the front of the house. “The door’s open. Want to look inside?”

“Of course,” said Rose, and grinned.

Helen frowned. “That’s trespassing.”

“Only if we get caught,” I replied.

We headed to the front door. I pushed it open and we went inside, entering a small anteroom that would be a mudroom if anyone lived there, and cluttered with boots and coats and gear. Now it was empty and spotless. We stepped cautiously through another doorway, into what must have been the living room.

“Wow.” Rose’s eyes widened. “Look at this.”

I blinked, shading my eyes. Bright as it had been outside, here it was even brighter. Sunlight streamed through the large windows. The hardwood floors were so highly polished they looked as though someone had spilled maple syrup on them. The ceiling was high, the walls unadorned with moldings or wainscoting, and painted white. I walked to one wall and laid my hand against it, the surface smooth and slightly warm to the touch. I rapped it gently with my knuckles. Plaster, not drywall, and smooth as a piece of glass. Not what I’d expect to find in a house this old, where the plaster should be cracked or pitted. It must have been refinished not long ago.

I turned to Rose and Helen. “Someone’s spent a lot of money here.”

“It doesn’t look like anyone’s ever been here,” replied Helen. She was crouched in one corner. “Not for ages. Look—this is the only electrical outlet in this room, and it must be almost a hundred years old.”

Helen and Rose wandered off. I could hear them laughing and exclaiming in amazement at what they found: an old-fashioned hand pump in the kitchen sink, water closet rather than a modern toilet. I stayed in the living room, enchanted by the light, which had an odd clarity. An empty room in a house this old should be filled with dust motes, but the sun pouring through the windows appeared almost solid. You hear about golden sunlight: this really did look solid, so much so that I took a step into the center of the room and swept my hand through the broad sunbeam that bisected the empty space. I felt nothing except a faint warmth.

“We’re going upstairs!” Rose yelled from another room.

I left the living room with reluctance—the days had grown shorter, soon it would be dark and that nice sunlight would be gone—but the hallway was nearly as bright, illuminated by glass sidelights beside the door and a half-moon fanlight above it. A single round window halfway up the steps made it easy to find my way to where Helen and Rose waited on the second-floor landing.

“I’m ready to make an offer,” Rose announced, and laughed. “Did you see how big those rooms downstairs are?”

I nodded. “You’d have to modernize everything.”

“Oh, I know. I’m just daydreaming. But it’s all so beautiful.”

“I can’t believe what good shape it’s in,” said Helen, whose husband was a carpenter. “I wonder who’s kept it up? I mean, someone can’t have been living here—no appliances.”

“Big pantry, though,” said Rose.

She turned and walked down the hall. Three doors opened onto it, each leading into a bedroom. The largest overlooked the road we’d walked up, with a heart-stopping view of trees in full autumn flame and the distant line of mountains. The other two rooms were smaller but still good-sized, bigger than our master bedroom at home. One looked up the slope of Mount Kilden, to the rocky outcropping up top called the Maidencliff, for a young girl who died there in the 1880s. She’d been picnicking with her family in the blueberry barren when her hat blew off, and she tumbled to her death as she chased after it.

In the other bedroom, you had a view of Lagawala Lake, which from here looked much larger than it did when Rose and I walked along the camp roads there.

“This would be my room,” I said, though no one was listening. The three of us went from one room to the next then back again, passing each other in the hallway and sharing observations.

“No bathroom—what would that have been like?”

“No heat, either.”

“There’s a floor register in the main bedroom. I guess the kids would just freeze.”

“They would probably have been two or three to a bed, back then,” said Helen, who had six grown or nearly-grown children. “That might have helped.”

“No lights, though.” I looked at the ceiling. “It would have been dark at night.”

“Yeah, but they’d have candles and lanterns and things like that. And people went to bed early then, too. Farmers, they have to get up at like three a.m.”

“I don’t think this was a farm,” I said, and peered out the window. “No fields or barns.”

Rose shook her head. “They could have owned all this land—it could all have been farms.”

“Maybe,” I said.

But I doubted it. Every farmhouse I’ve ever been in was sprawling and slightly ramshackle and comfortably messy—low-beamed ceilings, wood floors scuffed and uneven, walls dinged-up where kids had kicked them and showing evidence of having been painted and wallpapered numerous times over the years. The rooms opened one onto another and tended to be small, with few windows. And once they could afford it, farmers usually adopted new technology—electricity, milking machines, anything that would make their lives easier.

Electric lights and outlets would have marred the clean lines and planes of this house. I’ve been in plenty of old houses that have been up-to-dated, as the old timers put it, and ruined in the process.

Not this one. The bedrooms seemed to be almost perfectly square. Even the upstairs hallway felt square, though of course that was impossible. This symmetry could have felt restrictive, even claustrophobic. Instead, the plain white walls and warm-toned floors and carefully ordered doorways made me feel not calm, exactly, but quietly exhilarated. Like back when my husband Brandon and I would go to see a movie in the theater and we knew beforehand that it would be good and make us forget about everything else for a few hours. The house made me feel something like that.

“You know what else is weird?” asked Rose. “The way it smells.”

“It smells fine.” Helen glanced at me. “I don’t smell any mildew, do you, Marianne?”

“No,” I said. “But she’s right, that’s what’s weird—it doesn’t smell like mildew, or mice, or anything like that. And it doesn’t smell like paint, either, or polyurethane on the floors.”

We all took a final circuit of the three rooms, then trooped downstairs. Rose walked over to the brick fireplace—a Rumford fireplace, its angled sides designed to throw heat back into the living room. The hearth was immaculately clean, and so was the cast-iron bake oven set into the bricks. Rose opened and closed t

he oven door with a soft clang.

“You know what we should do?” she asked, and looked at us expectantly. “We should have a sleepover here.”

I said, “I’m in.”

Helen hesitated. “Someone would see us. People are still hiking up here.”

“They’re not hiking at night,” said Rose.

“No one would see us,” I said. “If we just have flashlights, no one’s going to notice.”

Helen mulled this over. “It’s going to be cold.”

“It’s cold in the state park lean-tos when we camp there in the fall.”

“But there we can have a fire.”

“Don’t be a wuss,” said Rose. “We can tell the boys we’re having a girl’s night in one of the lean-tos, if there’s an emergency or something they’ll call us and we can head home.”

“It’ll be fun,” I said, and looked out the window behind us. The sun had edged to the crest of Mount Kilden. The magical squares of gold light had shrunk to the size of a laptop screen. “It’ll be an adventure. I’ve always wanted to do something like this.”

“Breaking and entering?” Helen frowned.

“The door was unlocked,” said Rose. “Technically it would be civil trespassing—criminal trespassing means you broke in. If we come back here, and it’s locked, then we’ll just turn around and go home. Even if we did get caught, it’s only around a hundred dollar fine.”

Helen looked at her in disbelief. “How do you know so much about this?”

“I told you, I’ve always wanted to do it. Didn’t you ever think about it when you were a kid?”

“Yes,” Helen said. “But we’re all sixty years old.”

“That’s why it’s so important that we do it now,” said Rose.

“I’ll bring wine,” said Helen, and we all cheered.

I lowered my gaze to watch the last slim bars of light slide across the floor. For a few moments no one spoke. At last Helen said, “I’ve got to go home and get dinner going.”

Inferno

Inferno The Best of the Best Horror of the Year

The Best of the Best Horror of the Year When Things Get Dark

When Things Get Dark A Whisper of Blood

A Whisper of Blood Echoes

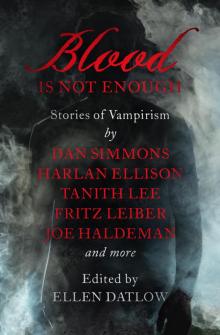

Echoes Blood Is Not Enough

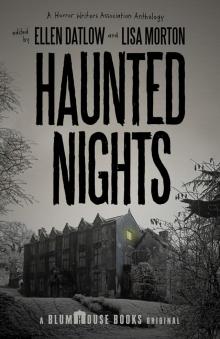

Blood Is Not Enough Haunted Nights

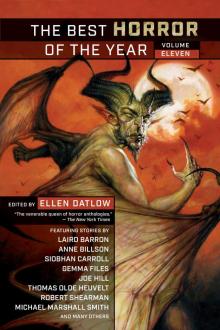

Haunted Nights The Best Horror of the Year Volume Eleven

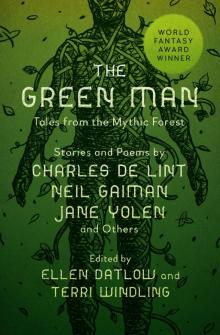

The Best Horror of the Year Volume Eleven The Green Man

The Green Man The Dark

The Dark Mad Hatters and March Hares

Mad Hatters and March Hares Nebula Awards Showcase 2009

Nebula Awards Showcase 2009 The Devil and the Deep

The Devil and the Deep