- Home

- Ellen Datlow

Inferno Page 4

Inferno Read online

Page 4

“Sad, all right.” Red set his own bottle down. “Just listening to him.”

“He’s got this whole thing, you see.” Buzz Cut tried to explain it to Ernie the bartender. “About how Hallowe’en has changed. It’s like really important to him. The poor sad bastard.”

“Yeah, right. I’ve heard it.” Ernie pointed around at the decorations. “He goes off about all this stuff, too.”

“Wait a minute.” It ticked him off, the way they were talking about him. In the third person, like he wasn’t even there. When he wasn’t even sure that they were there, or were just drug vapors. “Just because you guys—”

Set me as a seal upon your heart.

The whole bar went silent. As though they all could hear her now.

For a moment, she wasn’t draped across his back, her pale hands cuffed in front of his chest. She sat right next to him, leaning forward, those hands wrapped around her own beer. She turned and looked at him, beautiful and unsmiling, her dark hair a veil.

As a seal upon your arm, she whispered. For love is strong as death, passion fierce as the grave. She took a sip, then continued. Its flashes are flashes of fire, a raging flame …

“Okay, now I’m totally spooked.” He gripped the edge of the bar, forcing it to become real and solid. “Give me a break.”

She leaned over and kissed him. If all the wealth of our house were offered for love, she said, it would be utterly scorned. When he opened his eyes, she wasn’t sitting there anymore. Her hands pressed against his heart once more, her cold arms wrapped around him.

Still full of surprises, even dead; he had to give her that. Though not totally a surprise; she’d come up with stuff like that when they’d been together the first time. Pentecostalist childhood, for both of them. He recognized it: Song of Solomon, chapter eight, verses six and seven. There were some hot bits in that Bible book, favorites of hers. Though he couldn’t recall her spouting that one before.

“You gotta go back.” Ernie’s voice penetrated his meditations. “That’s what she’s trying to tell you.”

Maybe they had heard her. He didn’t know what that might mean. “Go back where? I already been all over town.”

“Not where. When. You gotta go back to when you went wrong. The two of you. And then do it right.”

“He’ll never make it.” Another voice came from the end of the bar. He looked and saw Edwin down there, stubbing out a cigarette butt in a drained highball glass. “He’s too screwed up.”

“Up yours.” The motorheads came to his defense. Buzz Cut nodded along with Red. “He can do it. We gave him all he needs. In this world, at least.”

“I’m not following this … .”

“Pay attention.” Ernie leaned over the bar, bringing his face close to his and the dead girl’s, as if they were in a football huddle. “I heard you out before. I know where you’re coming from. Believe me, I’ve heard it from other guys like you. You think the world changed out from under you, and that’s why things are all wrong.” Ernie tapped him on the brow. “But it’s the other way around. You changed. You gave up the old faith. You thought you could mess around all you wanted, and the world would still be the way it was, the way it’s supposed to be, when you got done. It doesn’t work that way.”

“Listen to the man.” Somebody shouted that from one of the tables in the corner of the bar. He glanced over his shoulder and saw the EMTs sitting there, empty bottles soldiered in front of them. And outside the bar—he could sense both the Metro patrol car and the tourist family from Idaho, slowly circling around. Except that he had made them up. So they at least were gone.

“Is this one of those Twilight Zone bits?” He felt even creepier than before. “You know, like where the guy is dead, only he thinks he’s still alive?”

“You should be so lucky,” said Ernie. “Don’t change the subject. Don’t try to get yourself off the hook. You want the world to be the way it should be? Then you need to go back and be the way you should’ve been. You and her.” Ernie reached out and stroked her dark hair, tenderly. “You should’ve been different. All this screwing around, and being trashy and wild—yeah, that’s fun and I’m happy to help you do it, but it doesn’t get the job done.”

“What job?”

“Come on. You and her, you were supposed to be the people handing out the candy. To the kids. On Hallowe’en. You were supposed to have a house, with a front door, and the bowlful of candy beside it. That’s what you were supposed to do. That was your job. Instead, you screwed around. All of you.” Ernie gestured toward the bar’s walls. “You think all this crap isn’t here for a reason? It’s because of you. People like you. Not doing your job. That’s how it got here.”

“Yeah, well, that’s real great. Telling me where—or when—I need to go, and all. Only problem is, there’s no way of getting there. It’s gone.”

“Strictly a technical problem.” Buzz Cut shrugged. “Just need to know how. That’s why you have friends like us.”

“What’s the matter?” Edwin had the kind of sneer that revealed a line of yellow teeth. “Didn’t you read Superman comics when you were a kid? You weren’t one of those Marvel faggots, were you?”

“What’s Superman got to do with it?”

“Don’t you remember?” Buzz Cut regarded him with pity. “Jeez, what a wasted childhood you must’ve had. No wonder you turned out this way.”

“When Superman needed to go back,” said Ernie, “remember how he did it?”

“Uh, that was a comic book.”

“Regardless. Remember how?”

“He went real fast.” A page full of bright yellows and reds and blues surfaced in his memory. “In a circle. Spinning, like.”

“Going in a circle doesn’t cut it. If you think about this.” Buzz Cut might have been explaining the difference between Keihin carbs and direct fuel injection. “It’s the going fast that does the trick. Obviously. Go fast enough, you can get anywhere. Or when. The spinning around in a circle, that was just so Superman would still be where he started out. Right? Otherwise, he would’ve gone back, but he would’ve been out around Neptune. Or Alpha Centauri or some other rat-ass place like that.”

“Going fast, huh?”

“That’s why people like to do it. Go fast, I mean. Even when they have no place to get to. Even when they’re just going around in circles. They know what they’re doing. They’re trying to get back. And you know what?” Buzz Cut leaned toward him, imparting a secret, but loud enough that everyone in the bar could hear. “Sometimes they do.”

Some of it made sense, some of it didn’t. “Don’t you have to go as fast as Superman? To make it work. Super fast?”

“Hell, no. That was just because Superman had to go back to ancient Egypt, or go fight dinosaurs or something. You don’t have that far to go.”

Red chimed in. “You just have to get back to where you went wrong. And start over. The two of you. That’s just not that far back.”

It’s not. Her whisper. Let’s go for it.

“And no circles?”

“I told you already. Head down, full tuck, and accelerate.” Buzz Cut got nods of agreement from the others along the bar. “Strictly straight line.”

“Kinda hard to tuck down behind the windscreen, with …” He tilted his head toward hers. “You know …”

“Do the best you can,” said Buzz Cut. “Do it right, you won’t even be outside the city limits. When you make it there.”

He knew what they were all going on about. “You mean the nitrous.”

“Well, of course. We put it on there for a reason. Now you know.”

Go for it.

They all watched him. Their gaze weighed heavier on him than she ever had.

They were right. Buzz Cut and the others, Ernie the bartender, even Edwin. They were right.

“I’m not paying you, though.” Edwin had pointed that out. “This is some other deal you got going.”

Once he got himself and her on the ’B

usa again, and started it up, he realized how right they were. He didn’t make it to the city limits. Out in empty desert again, sawtooth mountain silhouettes against the night sky—but if he had looked over his shoulder, he would still have been able to see the city’s clustered neon, a single blue-white beam bending its trajectory above him.

He didn’t need to look back. Her face was right next to his, her eyes closed, dreaming into the wind.

Straight shot, up into sixth gear, the road a knife’s edge in front of them, throttle rolled to the max. Nothing left but the red button on the handlebars, his leathered thumb already resting upon it.

Now’s the time.

Her whisper a kiss at his ear; he turned his cheek closer against the brush of her cold lips. He could barely breathe, she held him so tight. If his heart beat any stronger, it would break the links of the little chain.

Come on …

Or maybe the handcuffs had snapped apart already—he couldn’t feel them—and it was her own locked grip binding her to him. The way it had before, her eyes closed, velocity and dreamless. His hand at the center of a small world, trembling with both their pulses, every small motion a new possibility.

The button rose to meet his thumb. He pushed as hard as she did.

Then he knew why he had waited so long.

First to go was the ’Busa’s fairing, where it had cracked in the spill before. As the nitrous oxide poured into the engine and ignited, the stars blurred horizontal. A wall of air hit him, almost peeling him off the bike. In the rush that enveloped him, he could see but not hear the crack along the left side widen bigger than his gloved fist. It spidered into a jigsaw cobweb for only an instant, then shattered, the razor fragments swirling around him, then gone in the bike’s streaming wake.

Pinned, the tach and speedometer were useless now. He couldn’t even see them, unable to bring his sight down from the black horizon racing toward him.

Do it, she whispered somewhere. Harder.

The wind tore his jacket into tatters, stripped it from his chest. Her hands held tight, cupping his heart.

The front wheel came up from the road, spun free in hurtling air. The distant mountains tilted as he rolled in her embrace, face full against hers. He let go of the handlebars and pulled her tighter to himself, her knees crushing his hips. Beneath them, the motorcycle broke apart, into fire as meteors do, a matchflame struck against the earth’s atmosphere. Fiery bits of metal skittered along the road, white heat dying to red sparks.

“We’re not going back.” He turned and kissed her. “We’re here already.”

Lies and stories. There’d never been any going back. That’d all been crap they’d told him, that he’d told himself, to get to this point.

The old faith would have to do without them. If the children out at night looked up at the incendiary wound bleeding across the dark, they could take it as a sign.

Just before they struck the earth, she opened her eyes and looked into his. The road would strip their flesh away, their entwined bones charring to ash.

“Fierce.” She smiled. “As the grave.”

Misadventure

STEPHEN GALLAGHER

Stephen Gallagher was born in Salford, England, in 1954. He is the author of over a dozen novels including Nightmare, with Angel, Red, Red Robin, and The Spirit Box. He has numerous screenplay credits and in 1997 wrote and directed a TV adaptation of his novel Oktober . His short stories have been published in various magazines and anthologies including The Magazine of Fantasy & Science Fiction, Asimov’s Science Fiction, Weird Tales, Shadows, and The Dark; his collection Out of His Mind won a British Fantasy Award in 2004.

His latest novel is The Painted Bride and a new story collection will be published by Subterranean Press in 2007. His recently completed historical novel, The Kingdom of Bones, is to be published by Random House under the imprint of senior editor Shaye Areheart.

Four of us waited in the van, parked under a streetlamp on the bridge. Below us ran the motorway, a river of light in a valley of steel, a steady .L. flow of people with somewhere to be. Beside the motorway stood the gym and the parking lot that served it. Well-lit, but almost deserted now.

Outside the van, our foreman paced up and down. He had his phone in his hand. Every now and again he’d glance at it, checking the signal.

“They call him the Sheriff,” Peter the Painter said.

No one else responded, so I did.

“Why?”

Peter had his little finger stuck in his ear. He waggled it with a crackling sound and then inspected the result.

“You’ll find out,” he said, and wiped off on his overalls.

To look at us, you’d think we were a gang getting ready to rob the place. We were a rough-enough set of characters and nobody was in a mood for conversation. There was Peter the Painter, who I knew, and a couple of others who I didn’t. Miserable-looking types, both. Disappointed men who’d reckoned themselves cut out for something better. We all sat as far away from each other as it was possible to get. One of them lay across the back seat with his hand over his eyes, shading them from the lights.

“What’s going on down there?” Peter said, so I took a look.

“I think the boss is coming out,” I said.

The gym’s parking lot was floodlit but close to empty. The last of the customers had left about fifteen minutes before, and staff had been drifting out steadily ever since.

Two figures were now emerging through the glass doors. Outside the van, our foreman stopped his pacing and shaded his eyes for a better view. Way down below, the two appeared to be bidding each other good night. They were so far off that you’d need a sniper’s eyesight to be sure.

The last man waited until the other had driven away, and then he started to make a call. Almost immediately, our foreman’s phone played a tune.

It was a conversation that was over in just a few seconds.

“We’re on,” our foreman said as he got behind the wheel.

It took us no more than a couple of minutes to get down there. A gym doesn’t really describe it. You’d think you were looking at a factory unit, an immense low-rise building with no visible windows and all its air ducting on the outside. Inside were tennis courts, squash courts, swimming pool, sauna, and a weights room the size of a zeppelin hangar. On the outside, a second swimming pool and a barbecue terrace.

By the time we arrived, two more vans were on-site. Unlike ours, these were clean and had all their original doors and didn’t look as if gypsies had been keeping dogs in them. They had ladders on their roofs and the name of a building maintenance company on their sides. When we went into the club’s foyer to be briefed, the two men who’d arrived with them stayed apart from the rest of us.

Outside the doors, our foreman exchanged a few words with the gym’s manager and then the manager got into his car and drove away.

Then the foreman came inside.

“Right,” he said. “Here’s how it’s going to be. We’ve until the end of the week to get everything done. We can only work when the place is closed, which means from ten at night until seven in the morning.”

He winced, hitched up and scratched his nuts through his pants, and carried on. “Tonight we mask off all the switches and skirting boards. There’s some filling and sanding to be done. We need to drain the pool and clean it out—it’s a two-day job just to empty it, so there are waders in the van. Once it’s empty we need to recaulk the expansion joints and fill it up again. There are tiles to replace in the steam room, and locker doors to rehang in the changing areas. I’ll do a walk-around and show you where the work needs doing. Any questions?”

I said, “What about cameras?”

“The manager’s switched them off.”

And one of the men I didn’t know said to no one in particular, “I suppose that means he’s in on the deal.”

“Enough of that,” the foreman said. “You don’t care.”

It was about ten-thirty.

&

nbsp; I wondered why they called him the Sheriff.

Don’t ever let anyone tell you that a modern building with all its lights on can’t feel spooky. Only the tennis courts were dark, separated from the main walk-through by hanging nets. Also, the grille was down on the sports shop and they’d locked up the crèche. Otherwise everything was wide open and ablaze, and as we walked around it was like one of those movies where you wake up and you’re the last person on earth and you can go anywhere. The world’s your playground but it still feels as if you’re being daring. Someone had been through ahead of our arrival, spray-marking each of the job sites with a white arrow or otherwise pointing them up with colored tape or a note.

It was just snagging work, really. The building had been up for five years and the faults were no more than routine wear and tear. They were superficial but they made the place look bad. If the place looked bad then the members would complain. The membership would be families, mostly—so this wasn’t like a boxing gym or a back street hangout for bodybuilders, where a bit of exposed brick or a leaking roof only added to the ambience. This was pastels on the walls and ciabatta in the restaurant, and you’d better believe it.

The Sheriff assigned me to help Peter. The two newcomers, who he called Geordie and Jacko, were to work around the pool. They had to chisel out broken tiles in the steam room until the pool’s water level had dropped low enough for them to put on the waders and start scrubbing. All four of us stood there and watched as the Sheriff flipped back a cover and opened the sluice, and while he was doing it I heard the one called Geordie say, “Hey. What was that?”

He was looking out at the pool. After an hour without use it had settled to almost complete tranquillity, and its surface was like a vast blue gel. We were at the deep end, where it seemed to go on down for ever and ever.

“What was what?” I said.

He seemed about to answer, but then he changed his mind.

Peter the Painter lowered his voice to me as we were all walking along the side of the pool toward the exit.

Inferno

Inferno The Best of the Best Horror of the Year

The Best of the Best Horror of the Year When Things Get Dark

When Things Get Dark A Whisper of Blood

A Whisper of Blood Echoes

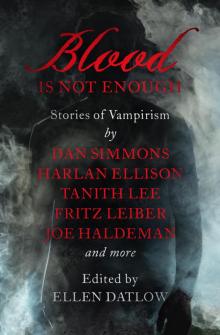

Echoes Blood Is Not Enough

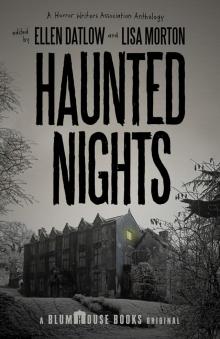

Blood Is Not Enough Haunted Nights

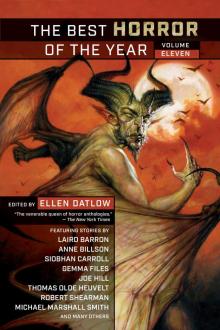

Haunted Nights The Best Horror of the Year Volume Eleven

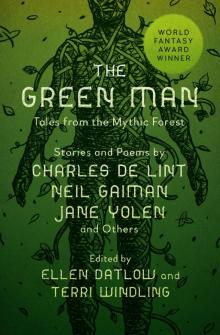

The Best Horror of the Year Volume Eleven The Green Man

The Green Man The Dark

The Dark Mad Hatters and March Hares

Mad Hatters and March Hares Nebula Awards Showcase 2009

Nebula Awards Showcase 2009 The Devil and the Deep

The Devil and the Deep