- Home

- Ellen Datlow

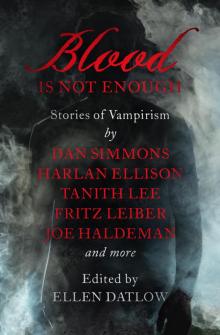

Blood Is Not Enough Page 6

Blood Is Not Enough Read online

Page 6

“Good-bye, Nina,” I said as I pulled Charles’s long pistol from the raincoat pocket. The explosion jarred my wrist and filled the room with blue smoke. A small hole, smaller than a dime but as perfectly round, appeared in the precise center of Nina’s forehead. For the briefest second she remained standing as if nothing had happened. Then she fell backward, recoiled from the high bed, and dropped face forward onto the floor.

I turned to the porter and replaced his useless weapon with the ancient but well-maintained revolver. For the first time I noticed that the boy was not much younger than Charles had been. His hair was almost exactly the same color. I leaned forward and kissed him lightly on the lips.

“Albert,” I whispered, “there are four cartridges left. One must always count the cartridges, mustn’t one? Go to the lobby. Kill the manager. Shoot one other person, the nearest. Put the barrel in your mouth and pull the trigger. If it misfires, pull it again. Keep the gun concealed until you are in the lobby.”

We emerged into general confusion in the hallway.

“Call for an ambulance!” I cried. “There’s been an accident. Someone call for an ambulance!” Several people rushed to comply. I swooned and leaned against a white-haired gentleman. People milled around, some peering into the room and exclaiming. Suddenly there was the sound of three gunshots from the lobby. In the renewed confusion I slipped down the back stairs, out the fire door, into the night.

Time has passed. I am very happy here. I live in southern France now, between Cannes and Toulon, but not, I am happy to say, too near St. Tropez.

I rarely go out. Henri and Claude do my shopping in the village. I never go to the beach. Occasionally I go to the townhouse in Paris or to my pensione in Italy, south of Pescara, on the Adriatic. But even those trips have become less and less frequent.

There is an abandoned abbey in the hills, and I often go there to sit and think among the stones and wild flowers. I think about isolation and abstinence and how each is so cruelly dependent upon the other.

I feel younger these days. I tell myself that this is because of the climate and my freedom and not as a result of that final Feeding. But sometimes I dream about the familiar streets of Charleston and the people there. They are dreams of hunger.

On some days I rise to the sound of singing as girls from the village cycle by our place on their way to the dairy. On those days the sun is marvelously warm as it shines on the small white flowers growing between the tumbled stones of the abbey, and I am content simply to be there and to share the sunlight and silence with them.

But on other days—cold, dark days when the clouds move in from the north—I remember the shark-silent shape of a submarine moving through the dark waters of the bay, and I wonder whether my self-imposed abstinence will be for nothing. I wonder whether those I dream of in my isolation will indulge in their own gigantic, final Feeding.

It is warm today. I am happy. But I am also alone. And I am very, very hungry.

I suspect that the vampire myth is as persistent, resilient, and satisfying as it is because there is a bit of the vampire in each of us. Much has been written about the blood symbolism in vampire tales, much about the latent erotic imagery, but little is said about the simple attraction of control. If you believe as I do that any exercise of power over another person is an incipient act of violence, then the vampire represents the ultimate violence—an extension of power over others to the grave and beyond.

“Carrion Comfort” has its genesis in a variety of places. There is a marvelous scene in the otherwise laughable 1931 Dracula where Bela Lugosi has a contest of wills with the aging Van Helsing. The old man staggers forward a few paces under the vampire’s influence and then pulls back painfully, slowly, struggling against invisible bonds. “You have a strong vill, Van Helsing,” smiles Lugosi. But we know who will win the contest in the end.

And of course any story or novel about extrasensory powers of control must recognize Frank M. Robinson’s The Power (1956) as a seminal influence.

In the end, however, it was the simple image of these three old people meeting in pleasant reunion, sunlight moving across their aged skin and young eyes, that proved the prime mover for “Carrion Comfort.” As many of us suspect, the road to success is littered with the brittle bones of our victims. After a while we do not notice.

We are what we devour.

Dan Simmons

THE SEA WAS WET AS WET COULD BE

Gahan Wilson

Lewis Carroll’s Alice in Wonderland and Through the Looking Glass are among my favorite works of fantasy. The books, in addition to being charming and entertaining, are deft commentaries on the economic, social, and political conditions of the times. And beneath some of the cute rhymes lurks genuine horror. So it is with “The Walrus and the Carpenter.” Gahan Wilson’s “The Sea Was Wet as Wet Could Be” is the story that prompted me to begin Blood Is Not Enough.

I felt we made an embarrassing contrast to the open serenity of the scene around us. The pure blue of the sky was unmarked by a single cloud or bird, and nothing stirred on the vast stretch of beach except ourselves. The sea, sparkling under the freshness of the early morning sun, looked invitingly clean. I wanted to wade into it and wash myself, but I was afraid I would contaminate it.

We are a contamination here, I thought. We’re like a group of sticky bugs crawling in an ugly little crowd over polished marble. If I were God and looked down and saw us, lugging our baskets and our silly, bright blankets, I would step on us and squash us with my foot.

We should have been lovers or monks in such a place, but we were only a crowd of bored and boring drunks. You were always drunk when you were with Carl. Good old, mean old Carl was the greatest little drink pourer in the world. He used drinks like other types of sadists used whips. He kept beating you with them until you dropped or sobbed or went mad, and he enjoyed every step of the process.

We’d been drinking all night, and when the morning came, somebody, I think it was Mandie, got the great idea that we should all go out on a picnic. Naturally, we thought it was an inspiration, we were nothing if not real sports, and so we’d packed some goodies, not forgetting the liquor, and we’d piled into the car, and there we were, weaving across the beach, looking for a place to spread our tacky banquet.

We located a broad, low rock, decided it would serve for our table, and loaded it with the latest in plastic chinaware, a haphazard collection of food and a quantity of bottles.

Someone had packed a tin of Spam among the other offerings and, when I saw it, I was suddenly overwhelmed with an absurd feeling of nostalgia. It reminded me of the war and of myself soldierboying up through Italy. It also reminded me of how long ago the whole thing had been and how little I’d done of what I’d dreamed I’d do back then.

I opened the Spam and sat down to be alone with it and my memories, but it wasn’t to be for long. The kind of people who run with people like Carl don’t like to be alone, ever, especially with their memories, and they can’t imagine anyone else might, at least now and then, have a taste for it.

My rescuer was Irene. Irene was particularly sensitive about seeing people alone because being alone had several times nearly produced fatal results for her. Being alone and taking pills to end the being alone.

“What’s wrong, Phil?” she asked.

“Nothing’s wrong,” I said, holding up a forkful of the pink Spam in the sunlight. “It tastes just like it always did. They haven’t lost their touch.”

She sat down on the sand beside me, very carefully, so as to avoid spilling the least drop of what must have been her millionth Scotch.

“Phil,” she said, “I’m worried about Mandie. I really am. She looks so unhappy!”

I glanced over at Mandie. She had her head thrown back and she was laughing uproariously at some joke Carl had just made. Carl was smiling at her with his teeth glistening and his eyes deep down dead as ever.

“Why should Mandie be happy?” I asked. “What, in God’s name, h

as she got to be happy about?”

“Oh, Phil,” said Irene. “You pretend to be such an awful cynic. She’s alive, isn’t she?”

I looked at her and wondered what such a statement meant, coming from someone who’d tried to do herself in as earnestly and as frequently as Irene. I decided that I did not know and that I would probably never know. I also decided I didn’t want anymore of the Spam. I turned to throw it away, doing my bit to litter up the beach, and then I saw them.

They were far away, barely bigger than two dots, but you could tell there was something odd about them even then.

“We’ve got company,” I said.

Irene peered in the direction of my point.

“Look, everybody,” she cried, “we’ve got company!”

Everybody looked, just as she had asked them to.

“What the hell is this?” asked Carl. “Don’t they know this is my private property?” And then he laughed.

Carl had fantasies about owning things and having power. Now and then he got drunk enough to have little flashes of believing he was king of the world.

“You tell em, Carl!” said Horace.

Horace had sparkling quips like that for almost every occasion. He was tall and bald and he had a huge Adam’s apple and, like myself, he worked for Carl. I would have felt sorrier for Horace than I did if I hadn’t had a sneaky suspicion that he was really happier when groveling. He lifted one scrawny fist and shook it in the direction of the distant pair.

“You guys better beat it,” he shouted. “This is private property!”

“Will you shut up and stop being such an ass?” Mandie asked him. “It’s not polite to yell at strangers, dear, and this may damn well be their beach for all you know.”

Mandie happens to be Horace’s wife. Horace’s children treat him about the same way. He busied himself with zipping up his windbreaker, because it was getting cold and because he had received an order to be quiet.

I watched the two approaching figures. The one was tall and bulky, and he moved with a peculiar, swaying gait. The other was short and hunched into himself, and he walked in a fretful, zigzag line beside his towering companion.

“They’re heading straight for us,” I said.

The combination of the cool wind that had come up and the approach of the two strangers had put a damper on our little group. We sat quietly and watched them coming closer. The nearer they got, the odder they looked.

“For heaven’s sake!” said Irene. “The little one’s wearing a square hat!”

“I think it’s made of paper,” said Mandie, squinting, “folded newspaper.”

“Will you look at the mustache on the big bastard?” asked Carl. “I don’t think I’ve ever seen a bigger bush in my life.”

“They remind me of something,” I said.

The others turned to look at me.

The Walrus and the Carpenter …

“They remind me of the Walrus and the Carpenter,” I said. “The who?” asked Mandie.

“Don’t tell me you never heard of the Walrus and the Carpenter?” asked Carl.

“Never once,” said Mandie.

“Disgusting,” said Carl. “You’re an uncultured bitch. The Walrus and the Carpenter are probably two of the most famous characters in literature. They’re in a poem by Lewis Carroll in one of the Alice books.”

“In Through the Looking Glass,” I said, and then I recited their introduction:

“The Walrus and the Carpenter

Were walking close at hand

They wept like anything to see

Such quantities of sand …

Mandie shrugged. “Well, you’ll just have to excuse my ignorance and concentrate on my charm,” she said.

“I don’t know how to break this to you all,” said Irene, “but the little one does have a handkerchief.”

We stared at them. The little one did indeed have a handkerchief, a huge handkerchief, and he was using it to dab at his eyes.

“Is the little one supposed to be the Carpenter?” asked Mandie.

“Yes,” I said.

“Then it’s all right,” she said, “because he’s the one that’s carrying the saw.” “He is, so help me, God,” said Carl. “And, to make the whole thing perfect, he’s even wearing an apron.”

“So the Carpenter in the poem has to wear an apron, right?” asked Mandie.

“Carroll doesn’t say whether he does or not,” I said, “but the illustrations by Tenniel show him wearing one. They also show him with the same square jaw and the same big nose this guy’s got.”

“They’re goddamn doubles,” said Carl. “The only thing wrong is that the Walrus isn’t a walrus, he just looks like one.”

“You watch,” said Mandie. “Any minute now he’s going to sprout fur all over and grow long fangs.”

Then, for the first time, the approaching pair noticed us. It seemed to give them quite a start. They stood and gaped at us and the little one furtively stuffed his handkerchief out of sight.

“We can’t be as surprising as all that!” whispered Irene.

The big one began moving forward, then, in a hesitant, tentative kind of shuffle. The little one edged ;ahead, too, but he was careful to keep the bulk of his companion between himself and us.

“First contact with the aliens,” said Mandie, and Irene and Horace giggled nervously. I didn’t respond. I had come to the decision that I was going to quit working for Carl, that I didn’t like any of these people about me, except, maybe, Irene, and that these two strangers gave me the honest creeps.

Then the big one smiled, and everything was changed.

I’ve worked in the entertainment field, in advertising and in public relations. This means I have come in contact with some of the prime charm boys and girls in our proud land. I have become, therefore, not only a connoisseur of smiles, I am a being equipped with numerous automatic safeguards against them. When a talcumed smoothie comes at me with his brilliant ivories exposed, it only shows he’s got something he can bite me with, that’s all.

But the smile of the Walrus was something else.

The smile of the Walrus did what a smile hasn’t done for me in years—it melted my heart. I use the corn-ball phrase very much on purpose. When I saw his smile, I knew I could trust him; I felt in my marrow that he was gentle and sweet and had nothing but the best intentions. His resemblance to the Walrus in the poem ceased being vaguely chilling and became warmly comical. I loved him as I had loved the teddy bear of my childhood.

“Oh, I say,” he said, and his voice was an embarrassed boom, “I do hope we’re not intruding!”

“I daresay we are,” squeaked the Carpenter, peeping out from behind his companion.

“The, uhm, fact is,” boomed the Walrus, “we didn’t even notice you until just back then, you see.”

“We were talking, is what,” said the Carpenter.

They wept like anything to see

Such quantities of sand …

“About sand?” I asked.

The Walrus looked at me with a startled air.

“We were, actually, now you come to mention it.”

He lifted one huge foot and shook it so that a little trickle of sand spilled out of his shoe.

“The stuff’s impossible,” he said. “Gets in your clothes, tracks up the carpet.”

“Ought to be swept away, it ought,” said the Carpenter.

’If seven maids with seven mops

Swept it for half a year,

Do you suppose,’ the Walrus said,

’That they could get it clear?’

“It’s too much!” said Carl.

“Yes, indeed,” said the Walrus, eying the sand around him with vague disapproval, “altogether too much.”

Then he turned to us again and we all basked in that smile.

“Permit me to introduce my companion and myself,” he said.

“You’ll have to excuse George,” said the Carpenter, “as he’s a bit of a stuff

ed shirt, don’t you know?”

“Be that as it may,” said the Walrus, patting the Carpenter on the flat top of his paper hat, “this is Edward Farr, and I am George Tweedy, both at your service. We are, uhm, both a trifle drunk, I’m afraid.”

“We are, indeed. We are that.”

“As we have just come from a really delightful party, to which we shall soon return.”

“Once we’ve found the fuel, that is,” said Farr, waving his saw in the air. By now he had found the courage to come out and face us directly.

“Which brings me to the question,” said Tweedy. “Have you seen any driftwood lying about the premises? We’ve been looking high and low and we can’t seem to find any of the blasted stuff.”

“Thought there’d be piles of it,” said Farr, “but all there is is sand, don’t you see?”

“I would have sworn you were looking for oysters,” said Carl. Again, Tweedy appeared startled.

’O Oysters, come and walk with us!’

The Walrus did beseech …

“Oysters?” he asked. “Oh, no, we’ve got the oysters. All we lack is the means to cook em.”

“’Course we could always use a few more,” said Farr, looking at his companion.

“I suppose we could, at that,” said Tweedy thoughtfully.

“I’m afraid we can’t help you fellows with the driftwood problem,” said Carl, “but you’re more than welcome to a drink.”

There was something unfamiliar about the tone of Carl’s voice that made my ears perk up. I turned to look at him, and then had difficulty covering up my astonishment.

It was his eyes. For once, for the first time, they were really friendly.

I’m not saying Carl had fishy eyes, blank eyes—not at all. On the surface, that is. On the surface, with his eyes, with his face, with the handling of his entire body, Carl was a master of animation and expression. From sympathetic, heart-felt warmth, all the way to icy rage, and on every stop in-between, Carl was completely convincing.

But only on the surface. Once you got to know Carl, and it took a while, you realized that none of it was really happening. That was because Carl had died, or been killed, long ago. Possibly in childhood. Possibly he had been born dead. So, under the actor’s warmth and rage, the eyes were always the eyes of a corpse.

Inferno

Inferno The Best of the Best Horror of the Year

The Best of the Best Horror of the Year When Things Get Dark

When Things Get Dark A Whisper of Blood

A Whisper of Blood Echoes

Echoes Blood Is Not Enough

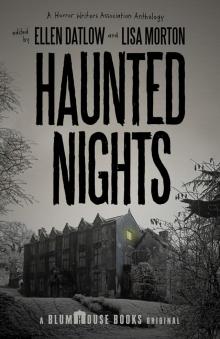

Blood Is Not Enough Haunted Nights

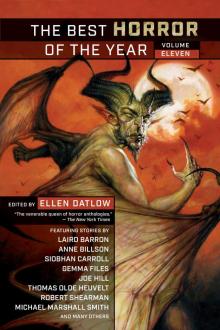

Haunted Nights The Best Horror of the Year Volume Eleven

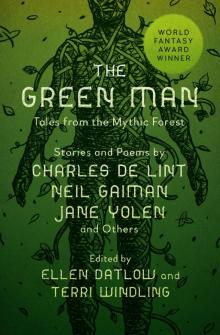

The Best Horror of the Year Volume Eleven The Green Man

The Green Man The Dark

The Dark Mad Hatters and March Hares

Mad Hatters and March Hares Nebula Awards Showcase 2009

Nebula Awards Showcase 2009 The Devil and the Deep

The Devil and the Deep