- Home

- Ellen Datlow

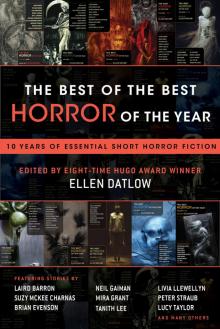

The Best of the Best Horror of the Year Page 9

The Best of the Best Horror of the Year Read online

Page 9

“Okay?” he said.

I nodded, trembling. “I think. You?”

He started to laugh. “Holy shit,” he said. “Holy crazy Canadian shit.”

It wasn’t funny. But with Alex there, you couldn’t help smiling anyway. Jamie was doing it, too, while pointlessly patting over and over at my face. I took her hand to stop her. Then I just held onto that.

We were back in our seats, our heads wrapped in scratchy airline towels, ears still ringing, hands still shaking but settled firmly on the controls that would guide us either safely back to the terminal or up in the air and as far from Prince Willows Town as this plane’s pathetic fuel tanks could carry us, when the cockpit door opened. Alex was the one who turned. Then he said, “Wayne.”

I turned, too. Jamie stood in the doorway, face waxy, eyes blank. “He’s gone,” she said.

“What?” I asked.

“The guy in 2B. The crying guy. He’s not on the plane. He didn’t go out past me either. He’s nowhere.”

I stood up, shaking my head. “That’s ridiculous. He must have—”

“Wayne,” Jamie said, and her eyes filled with tears. “He’s gone.”

It happened only occasionally, Bill told me once, years later, over one final round of Molsons, before both of us left the flying game for good. Only in the dead of winter, on the coldest nights. Mostly not even then. No one really knew when or how the realization had been made about the de-icing fluid. But that seemed to help. Sometimes. To keep them back. Sometimes.

“Always so sad,” Bill had said. “Always, always, always.”

At least, that’s what I thought he’d said. It wasn’t until that night, back in my hotel, pouring a drink, that my hands started to shake, and I realized I’d heard him wrong. Not so sad. The sad. Always the sad.

Was it grief that drew them? Or reacted with something else in that air, in those woods, and created them? Had my grief drawn or created them? If so, it wasn’t the anti-freeze that saved me. It was the sobbing man. His was fresher.

Had they swallowed him? I like to think he was one of them, now, instead. Reunited, maybe, with what he’d lost. Or at least in company, with the Nimble Men. Sometimes, that thought comforts me.

You can’t fly to Prince Willows Town, any more. Not long after that night, they closed the facility, redirecting all traffic to the bigger, better-serviced airport at Sudbury, where the light-towers are numerous and brighter, and the trees keep their distance.

LITTLE AMERICA

DAN CHAON

First of all, here are the highways of America. Here are the states in sky blue, pink, pale green, with black lines running across them. Peter has a children’s version of the map, which he follows as they drive. He places an X by the names of towns they pass by, though most of the ones on his old map aren’t there anymore. He sits, staring at the little cartoons of each state’s products and services. Corn. Oil wells. Cattle. Skiers.

Secondly, here is Mr. Breeze himself. Here he is behind the steering wheel of the long old Cadillac. His delicate hands are thin, reddish as if chapped. He wears a white shirt, buttoned at the wrist and neck. His thinning hair is combed neatly over his scalp, his thin, skeleton head is smiling. He is bright and gentle and lively, like one of the hosts of the children’s programs Peter used to watch on television. He widens his eyes and enunciates his words when he speaks.

Third is Mr. Breeze’s pistol. It is a Glock 19 nine millimeter compact semi-automatic handgun, Mr. Breeze says. It rests enclosed in the glove box directly in front of Peter, and he imagines that it is sleeping. He pictures the muzzle, the hole where the bullet comes out: a closed eye that might open at any moment.

Outside the abandoned gas station, Mr. Breeze stands with his skeleton head cocked, listening to the faintly creaking hinge of an old sign that advertises cigarettes. His face is expressionless, and so is the face of the gas station storefront. The windows are broken and patched with pieces of cardboard, and there is some trash, some paper cups and leaves and such, dancing in a ring on the oil-stained asphalt. The pumps are just standing there, dumbly.

“Hello?” Mr. Breeze calls after a moment, very loudly. “Anyone home?” He lifts the arm of a nozzle from its cradle on the side of a pump and tries it. He pulls the trigger that makes the gas come out of the hose, but nothing happens.

Peter walks alongside Mr. Breeze, holding Mr. Breeze’s hand, peering at the road ahead. He uses his free hand to shade his eyes against the low late afternoon sun. A little ways down are a few houses and some dead trees. A row of boxcars sitting on the railroad track. A grain elevator with its belfry rising above the leafless branches of elms.

In a newspaper machine is a USA Today from August 6, 2012, which was, Peter thinks, about two years ago, maybe? He can’t quite remember.

“It doesn’t look like anyone lives here anymore,” Peter says at last, and Mr. Breeze regards him for a long moment in silence.

At the motel, Peter lies on the bed, face down, and Mr. Breeze binds his hands behind his back with a plastic tie.

“Is this too tight?” Mr. Breeze says, just as he does every time, very concerned and courteous.

And Peter shakes his head. “No,” he says, and he can feel Mr. Breeze adjusting his ankles so that they are parallel. He stays still as Mr. Breeze ties the laces of his tennis shoes together.

“You know that this is not the way that I want things to be,” Mr. Breeze says, as he always does.

“It’s for your own good.”

Peter just looks at him, with what Mr. Breeze refers to as his “inscrutable gaze.”

“Would you like me to read to you?” Mr. Breeze asks. “Would you like to hear a story?”

“No, thank you,” Peter says.

In the morning, there is a noise outside. Peter is on top of the covers, still in his jeans and T-shirt and tennis shoes, still tied up, and Mr. Breeze is beneath the covers in his pajamas, and they both wake with a start. Beyond the window, there is a terrible racket. It sounds like they are fighting or possibly killing something. There is some yelping and snarling and anguish, and Peter closes his eyes as Mr. Breeze gets out of bed and springs across the room on his lithe feet to retrieve the gun.

“Shhhh,” Mr. Breeze says, and mouths silently: “Don’t. You. Move.” He shakes his finger at Peter: no no no! and then smiles and makes a little bow before he goes out the door of the motel with his gun at the ready.

Alone in the motel room, Peter lies breathing on the cheap bed, his face down and pressed against the old polyester bedspread, which smells of mildew and ancient tobacco smoke.

He flexes his fingers. His nails, which were once long and black and sharp, have been filed down to the quick by Mr. Breeze—for his own good, Mr. Breeze had said.

But what if Mr. Breeze doesn’t come back? What then? He will be trapped in this room. He will strain against the plastic ties on his wrist, he will kick and kick his bound feet, he will wriggle off the bed and pull himself to the door and knock his head against it, but there will be no way out. It will be very painful to die of hunger and thirst, he thinks.

After a few minutes, Peter hears a shot, a dark firecracker echo that startles him and makes him flinch.

Then Mr. Breeze opens the door. “Nothing to worry about,” Mr. Breeze says. “Everything’s fine!”

For a while, Peter had worn a leash and collar. The skin-side of the collar had round metal nubs that touched Peter’s neck and would give him a shock if Mr. Breeze touched a button on the little transmitter he carried.

“This is not how I want things to be,” Mr. Breeze told him. “I want us to be friends. I want you to think of me as a teacher. Or an uncle!

“Show me that you’re a good boy,” Mr. Breeze said, “And I won’t make you wear that anymore.”

In the beginning, Peter had cried a lot, and he had wanted to get away, but Mr. Breeze wouldn’t let him go. Mr. Breeze had Peter wrapped up tight and tied in a sleeping bag with just his head sticking out—wrig

gling like a worm in a cocoon, like a baby trapped in its mother’s stomach.

Even though Peter was nearly twelve years old, Mr. Breeze held him in his arms and rocked him and sang old songs under his breath and whispered shh shhh shhhh. “It’s okay, it’s okay,” Mr. Breeze said. “Don’t be afraid, Peter, I’ll take care of you.”

They are in the car again now, and it is raining. Peter leans against the window on the passenger side, and he can see the droplets of water inching along the glass, moving like schools of minnows, and he can see the clouds with their gray, foggy fingerlings almost touching the ground, and the trees bowed down and dripping.

“Peter,” Mr. Breeze says, after an hour or more of silence. “Have you been watching your map? Do you know where we are?”

And Peter gazes down at the book Mr. Breeze had given him. Here are the highways, the states in their pale primary colors. Nebraska. Wyoming.

“I think we’re almost halfway there,” Mr. Breeze says. He looks at Peter and his cheerful children’s-program eyes are careful, you can see him thinking something besides what he is saying. There is a way that an adult can look into you to see if you are paying attention, to see if you are learning, and Mr. Breeze’s eyes scope across him, prodding and nudging.

“It’s a nice place,” Mr. Breeze says. “A very nice place. You’ll have a room of your own. A warm bed to sleep in. Good food to eat. And you’ll go to school! I think you’ll like it.”

“Mm,” Peter says, and shudders.

They are passing a cluster of houses now, some of them burned and still smoldering in the rain. There are no people left in those houses, Peter knows. They are all dead. He can feel it in his bones; he can taste it in his mouth.

Also, out beyond the town, in the fields of sunflowers and alfalfa, there are a few who are like him. Kids. They are padding stealthily along the rows of crops, their palms and foot soles pressing lightly along the loamy earth, leaving almost no track. They lift their heads, and their golden eyes glint.

“I had a boy once,” Mr. Breeze says.

They have been driving without stopping for hours now, listening to a tape of a man and some children singing. B-I-N-G-O, they are singing. Bingo was his name-o!

“A son,” Mr. Breeze says. “He wasn’t so much older than you. His name was Jim.”

Mr. Breeze moves his hands vaguely against the steering wheel.

“He was a rock hound,” Mr. Breeze says. “He liked all kinds of stones and minerals. Geodes, he loved. And fossils! He had a big collection of those!”

“Mm,” Peter says.

It is hard to picture Mr. Breeze as a father, with his gaunt head and stick body and puppet mouth. It is hard to imagine what Mrs. Breeze must have looked like. Would she have been a skeleton like him, with a long black dress and long black hair, a spidery way of walking?

Maybe she was his opposite: a plump young farm girl, blond and ruddy-cheeked, smiling and cooking things in the kitchen like pancakes.

Maybe Mr. Breeze is just making it up. He probably didn’t have a wife or son at all.

“What was your wife’s name?” Peter says, at last, and Mr. Breeze is quiet for a long time. The rain slows, then stops as the mountains grow more distinct in the distance.

“Connie,” Mr. Breeze says. “Her name was Connie.”

By nightfall, they have passed Cheyenne—a bad place, Mr. Breeze says, not safe—and they are nearly to Laramie, which has, Mr. Breeze says, a good, organized militia and a high fence around the perimeter of the city.

Peter can see Laramie from a long way off. The trunks of the light poles are as thick and tall as sequoias, and at their top, a cluster of halogen lights, a screaming of brightness, and Peter knows he doesn’t want to go there. His arms and legs begin to itch, and he scratches with his sore, clipped nails, even though it hurts just to touch them to skin.

“Stop that, please, Peter,” Mr. Breeze says softly, and when Peter doesn’t stop he reaches over and gives Peter a flick on the nose with his finger. “Stop.” Mr. Breeze says. “Right. Now.”

There are blinking yellow lights ahead, where a barrier has been erected, and Mr. Breeze slows the Cadillac as two men emerge from behind a structure made of logs and barbed wire and pieces of cars that have been sharpened into points. The men are soldiers of some kind, carrying rifles, and they shine a flashlight in through the windshield at Peter and Mr. Breeze. Behind them, the high chain fence makes shadow patterns across the road as it moves in the wind.

Mr. Breeze puts the car into park and reaches across and takes the gun from its resting place in the glove box. The men are approaching slowly and one of them says very loudly: “STEP OUT OF THE CAR PLEASE SIR,” and Mr. Breeze touches his gun to Peter’s leg.

“Be a good boy, Peter,” Mr. Breeze whispers. “Don’t you try to run away, or they will shoot you.”

Then Mr. Breeze puts on his broad, bright puppet smile. He takes out his wallet and opens it so that the men can see his identification, so that they can see the gold seal of the United States of America, the glinting golden stars. He opens his door and steps out. The gun is tucked into the waistband of his pants, and he holds his hands up loosely, displaying the wallet.

He shuts the door with a thunk, leaving Peter sealed inside the car.

There is no handle on the passenger side of the car, so Peter cannot open his door. If he wanted to, he could slide across to the driver’s seat, and open Mr. Breeze’s door, and roll out onto the pavement and try to scramble as fast as he could into the darkness, and maybe he could run fast enough, zig-zagging, so that the bullets they’d shoot would only nip the ground behind him, and he could find his way into some kind of brush or forest and run and run until the voices and the lights were far in the distance.

But the men are watching him very closely. One man is holding his flashlight so that the beam shines directly through the windshield and onto Peter’s face, and the other man is staring at Peter as Mr. Breeze speaks and gestures, speaks and gestures like a performer on television who is selling something for kids. But the man is shaking his head no. No!

“I don’t care what kind of papers you got, mister,” the man says. “There’s no way you’re bringing that thing through these gates.”

Peter used to be a real boy.

He can remember it—a lot of it is still very clear in his mind. “I pledge allegiance to the flag” and “Knick knack paddy whack give a dog a bone this old man goes rolling home” and “ABCDEFGHIJKLMNOPQRSTUVWXYZ now I know my ABCs, next time won’t you sing with me?” and “Yesterday … all my troubles seemed so far away” and …

He remembers the house with the big trees in front, riding a scooter along the sidewalk, his foot pumping and making momentum. The bug in a jar—cicada—coming out of its shell and the green wings. His mom and her two braids. The cereal in a bowl, pouring milk on it. His dad flat on the carpet, climbing on his Dad’s back: “Dog pile!”

He can still read. The letters come together and make sounds in his mind. When Mr. Breeze asked him, he found he could still say his telephone number and address, and the names of his parents.

“Mark and Rebecca Krolik,” he said. “Two one three four Overlook Boulevard, South Bend, Indiana four six six oh one.”

“Very good!” Mr. Breeze said. “Wonderful!”

And then Mr. Breeze said, “Where are they now, Peter? Do you know where your parents are?”

Mr. Breeze pulls back from the barricade of Laramie and the gravel sputters out from their tires and in the rearview mirror Peter can see the men with their guns in the red taillights and dust.

“Damn it,” Mr. Breeze says, and slaps his hand against the dashboard. “Damn it! I knew I should have put you in the trunk!” And Peter says nothing. He has never seen Mr. Breeze angry in this way, and it frightens him—the red splotches on Mr. Breeze’s skin, the scent of adult rage—though he is also relieved to be moving away from those big halogen lights. He keeps his eyes straight ahead and his hands folded in hi

s lap, and he listens to the silence of Mr. Breeze unraveling, he listens to the highway moving beneath them, and watches as the yellow dotted lines at the center of the road are pulled endlessly beneath the car. For a while, Peter pretends that they are eating the yellow lines.

After a time, Mr. Breeze seems to calm. “Peter,” he says. “Two plus two.”

“Four,” Peter says softly.

“Four and four.”

“Eight.”

“Eight and eight.”

“Sixteen,” Peter says, and he can see Mr. Breeze’s face in the bluish light that glows from the speedometer. It is the cold profile of a portrait, like the pictures of people that are on money. There is the sound of the tires, the sound of velocity.

“You know,” Mr. Breeze says at last. “I don’t believe that you’re not human.”

“Hm,” Peter says.

He thinks this over. It’s a complicated sentence, more complicated than math, and he’s not sure he knows what it means. His hands rest in his lap, and he can feel his poor clipped nails tingling as if they were still there. Mr. Breeze said that after a while he will hardly remember them, but Peter doesn’t think this is true.

“When we have children,” Mr. Breeze says, “they don’t come out like us. They come out like you, Peter, and some of them even less like us than you are. It’s been that way for a few years now. But I have to believe that these children – at least some of these children—aren’t really so different, because they are a part of us, aren’t they? They feel things. They experience emotions. They are capable of learning and reason.”

“I guess,” Peter says, because he isn’t sure what to say. There is a kind of look an adult will give you when they want you to agree with them, and it is like a collar they put on you with their eyes, and you can feel the little nubs against your neck, where the electricity will come out. Of course, he is not like Mr. Breeze, nor the men that held the guns at the gates of Laramie; it would be silly to pretend, but this is what Mr. Breeze seems to want. “Maybe,” Peter says, and he watches as they pass a green luminescent sign with a white arrow that says Exit.

Inferno

Inferno The Best of the Best Horror of the Year

The Best of the Best Horror of the Year When Things Get Dark

When Things Get Dark A Whisper of Blood

A Whisper of Blood Echoes

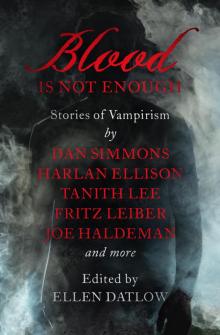

Echoes Blood Is Not Enough

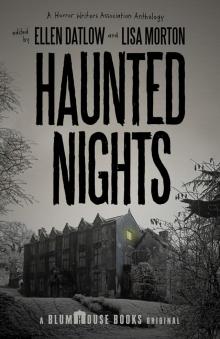

Blood Is Not Enough Haunted Nights

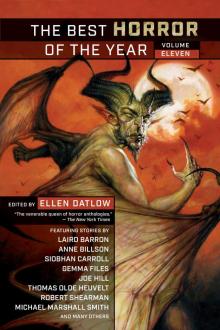

Haunted Nights The Best Horror of the Year Volume Eleven

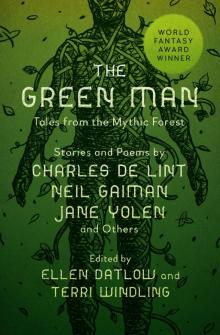

The Best Horror of the Year Volume Eleven The Green Man

The Green Man The Dark

The Dark Mad Hatters and March Hares

Mad Hatters and March Hares Nebula Awards Showcase 2009

Nebula Awards Showcase 2009 The Devil and the Deep

The Devil and the Deep