- Home

- Ellen Datlow

The Best of the Best Horror of the Year Page 14

The Best of the Best Horror of the Year Read online

Page 14

As we leave the park, I can hear the long howls behind me, the humanity disintegrating from those poor people’s voices. My grandchildren laugh out loud, giddy from the experience. These changes always seem to happen around certain members of my family, although none of us have precisely understood the relationship or the mechanism. Why did the couple change but not the ranger? I have no idea. Perhaps it is some tendency in the mind, some proclivity of the imagination, or some random, genetic bullet. My grandchildren possess a prodigious talent, but it’s not a talent anyone would want to see in action.

Up in the front passenger seat, Jackie pats Robert’s shoulder. I don’t know if this is meant as encouragement, or if he even needs it. My son has always been sane to a fault. His wife’s face looks worried, the skin so tight across her cheeks and chin it’s as if she wears a latex mask. But then Jackie always was the nervous sort. She’s not of this family; she simply married into it.

“Dad, I thought I asked you not to tell them any more stories.” Robert’s voice is barely under control.

They’re both angry with me, furious. They blame me for all of this. But they try not to show it. I don’t think it’s because they’re careful with my feelings. I think it’s because they’re somewhat frightened of me. “Telling stories, that’s what grandfathers do,” I say. “It’s how I can communicate with them. The stories of our lives and deaths are secrets even from ourselves. All we are able to share are these substandard approximations. But we still have to try, unless we want to arm ourselves with loneliness. I just tell the children fairy tales, Robert. That’s all. Stories about monsters. Something they already know about. Monster stories won’t turn you into a monster, son. Fairy tales simply tell you something you already knew in a somewhat clever way.”

Once upon a time, perhaps gods and monsters walked the earth and a human might choose to be either one. But not anymore. Now people grow and age and die and then are forgotten about. It’s the “great circle,” or whatever you want to call it. It’s sobering information but it can’t be helped. I don’t tell Robert this—he isn’t ready to hear it. He loves his poor, pathetic flesh too much.

“Why couldn’t you stop? What will it take to make you stop!” Robert is howling from behind the steering wheel. For just a moment, I think he’s about to change, expand, become some sort of wolf thing, but he is simply upset with me. Robert is our only child, and I love him very much, but he has always been vulnerable, frightened by the most mundane of dangers, as if he were unhappy to have been born a mortal human (I’m afraid the only kind there is).

Robert always refused to listen to my bedtime stories, so he’s really in no place to evaluate whether they are dangerous or not. The members of our family have been shunned for ages, thought to be witches, demons, and worse. No one wants to hear what we have to say. “Your children simply understand the precariousness of it all. And this is how they express it.”

“No more, Dad, okay? No more today.”

Whatever my son decides to do, he’s likely to keep us all locked up at home from now on. The only reason we went out today was because he knows the children need to get out now and then, and he didn’t think we’d run into anybody in that big state park. Besides, it doesn’t happen every time, not even every other time. There’s no way to predict such things. I’ve witnessed these transformations again and again, but even I do not understand the agency involved.

I can’t blame him, I guess. Sometimes human life makes no sense. We really shouldn’t exist at all.

Back at the old farmhouse, I’m suddenly so exhausted I can barely get out of the car. It’s as if I’ve had a huge meal and now all I can manage is sleep. The adrenalin of the previous few hours has come with a cost. I suspect my food must eat me rather than the other way around.

Alicia is even worse than before, and Robert and Jackie each have to pull on an arm to get her to stand. The grandkids push on her butt, giggling, and aren’t really helping.

Once inside, they take us up to our room. “I get so exhausted,” I tell them.

“I know,” Jackie replies. “You should just make it stop. We’d all be happier if you just made it stop.”

She’s like all the others. She doesn’t understand. It happens, but I’ve never been sure we can make it happen. Perhaps we simply show what has always been. Her children are learning about death. It’s a lesson not everyone wants to learn.

She must think that, because I’m an older man, I’m likely to do foolish things. But we have such a limited time on this planet, I want to tell her, why should we avoid the foolish? I feel like that deliverer of bad news whom everyone blames.

Robert is less courteous as he guides us up the stairs, his movements abrupt and careless. He’s obviously lost all patience with this—this caring for elderly parents, this endless drama whenever the family goes out. He’ll make us all stay home now, planted in front of the television, transfixed by god-knows-what mindless comedy, locked away so that we can’t cause any more trouble. But the children have to go out now and then. An active child trapped inside is like a bomb waiting to go off.

Periodically he loses his balance and crashes me into a railing, a wall, the doorframe. Each time he apologizes but I suspect it is intentional. I don’t mind especially—each small jolt of pain wakes me up a bit more. You have to stay awake, I think, in order to know which world you’re in.

By the time they lay both of us down in the bed, I’m practically blind with fatigue. Almost everything is a dirty yellow smear. It’s like a glimpse of an old photograph whose colors have receded into a waxy sheen. Perhaps this is the start of sleep, or the beginning of something else.

Several times during the middle of the night, Alicia crawls beneath the bed. Is this what a nightmare is like? Sometimes I crawl under the bed with her. The floor is gritty, dirty, and uncomfortable to lie on. It’s like a taste of the grave. It’s what I have to look forward to.

I pat Alicia’s arm when she cries. “At least you still have your yellow hair,” I tell her. She looks at me so fiercely I back away, far far back under the bed into the shadows where I can hear the winds howl and the insects’ mad mutter. I can stay there only a brief while before it sickens me but it still seems safer than lying close to her.

I wake up the next morning with my hand completely numb, sleeping quietly beside my face. I scrape the unfeeling flesh against the rough floorboards until it appears to come back to life. Alicia isn’t here; she’s wandered off. Although much of the time she is practically immobile, she has these occasional adrenaline-driven spurts in which she moves until she falls down or someone catches her. She is so arthritic, these bouts of intense activity must be agony for her. I can hear the grandchildren laughing outside and there is this note in their tone that drives me to the window to see.

The two darlings have the mail carrier cornered by the garage. We never get mail here and I think how sad it is that this poor man will doubtless lose his life over an erroneous delivery. They chatter away with their monkey-like talk at such a high pitch and speed I cannot follow what they say, but the occasional discrete image floats to the top—screaming heads and bodies in flame. None of these images appears in any of the stories I have told them, although of course Robert will never believe this. What he does not fully appreciate is that out in the real world all heads have the potential for screaming, and all bodies are in fact burning all the time.

On the edge of the yard, I spy Alicia. She has taken off all her clothes again and now scratches about on all fours like some different kind of animal. The Roberts of the world do not wish to admit that humans are animals. We may fancy ourselves better than the beasts because of our language skills, because we possess words in abundance. But all that does is empower us with excuses and equivocations.

The mail carrier has begun to change. He struggles valiantly but to no avail. Already his jaw has lengthened until it disconnects from the rest of his face, wagging back and forth with no muscle to support it. Already his

hair drifts away and his fleshier bits have begun to dissolve. These are changes typical, I think, of a body left in the ground for months.

At first Evie laughs as if watching a clown running through his repertoire of shenanigans but now she has begun to cry. Such is the madness of children, but I must do what I can to minimize the damage. I make my way stiffly downstairs with a desperate grip on the banister, my joints like so much broken glass inside my flesh, and as I head for the door I see Robert come up out of the cellar, the axe in his hands. “This has to stop ... this has to stop,” he screams at me. And I very much agree. And if he were coming for me with that axe all would be fine—I somehow always understood things might come to this juncture—but he sweeps past me and heads for the front door and my grandchildren outside.

I take a few quick steps, practically falling, and shove him away from the door. I see his hands fumble the axe, but I do not realize the danger until he hits the wall and screams, tumbles backwards, the blade buried in his chest. “Robert!”

It’s all I have time to say before Jackie comes out of the kitchen screeching. But it’s all I know to say, really, and what good would it do to lose myself now? He would have hated to die from clumsiness, and that’s what I take away from this house when I leave.

Out on the lawn, the children are jumping up and down laughing and crying. There is a moment in which time slows down, and I’m heartsick to see their tiny perfect features shift, coarsen, the flesh losing its elasticity and acquiring a dry, plastic filler look, as if they might become puppets, inanimate figures controlled by distant and rapidly-vanishing souls. I see my little Evie’s eyes dull into dark marbles, her slackened face and collapsing mouth spilling the dregs of her laughter. I think of Robert dead in the farmhouse—and what a mad and reprehensible thing it is to survive one’s child.

But of course I can’t tell these children their father has died. Maybe later, but not now, when they are like this. If I told them now they might savage the little that remains of our pitiful world. In fact, I can’t tell them anything I feel or know or see.

“Help me find your grandmother!” I shout. “She’s gotten away from us, but I’m sure one of you clever children will find her!” And I am relieved when they follow me out of the yard and into the edge of the woods.

I have even more difficulty as I maneuver through the snarled tangle of undergrowth and fallen branches than I thought I would. I’m out of practice, and with every too-wide step to avoid an obstacle, I’m sure I’m going to fall. But the children don’t seem to mind our lack of progress; in fact, they already appear to have forgotten why we’re out here. They range back and forth, their paths cross as they pretend to be bees or birds or low-flying aircraft. Periodically they deliberately crash into each other, fall back against trees and bushes in dozens of feigned deaths. Sometimes they just break off to babble at each other, point at me, and giggle, sharing secrets in their high-pitched alien language.

Now and then I snatch glimpses of Alicia moving through the trees ahead of us. Her blonde hair, her long legs, and once or twice just a bit of her face, and what might be a smile or a grimace; I can’t really tell from this distance. Seeing her in fragments like this, I can almost imagine her as the young athletic woman I met fifty years ago, so quick-witted, who enthralled me and frightened me and ran rings around me in more ways than one. But I know better. I know that that young woman exists more in my mind, now, than in hers. That other Alicia is now like some shattered carcass by the roadside, and what lives, what dances and races and gibbers mindlessly among trees is a broken spirit that once inhabited that same beautiful body. Sometimes the death of who we’ve loved is but the final act in a grief that has lingered for years.

I think that if Alicia were to embrace me now, she’d have half my face between her teeth before I had time even to speak her name.

As mad as she, the children now shriek on either side of me, slap me on the side of the face, the belly, before they howl and run away. I wonder if they even remember who she is or was to them. How only a few years ago, she made them things and cuddled them and sang them soft songs. But we were never meant to remember everything, I think, and that is a blessing. It seems they have already forgotten about their parents, except as a story they used to know. The young are always more interested in science fiction, those fantasies of days to come, especially if they can be the heroes.

I watch them, or I avoid them, for much of the afternoon. Like a baby sitter who really doesn’t want the job. At one point, they begin to fight over a huge burl on a tree about three feet off the ground. It is only the second such tree deformity I’ve ever seen, and by far the larger of the two. I understand that they come about when the younger tree is damaged and the tree continues to grow around the damage to create these remarkable patterns in the grain.

Their argument is a strange one, although not that different from other arguments they’ve had. Evie says it’ll make a perfect “princess throne” for her after they cut it down. The fact that they have no means to cut it down does not factor into the argument. Tom claims he “saw it first,” and although he has no idea what to do with it, the right to decide should be his.

Eventually they come to blows, both of them crying as they continue to pummel each other about the head and face. When they begin to bleed, I decide I have to do something. I have handled this badly, although I can’t imagine that anyone else would know better how to handle such a crisis. I stare at them—their flesh is running. Their flesh runs! Their grandmother is gone, and they don’t even know that their father is dead. And they dream wide awake and the flesh flows around them.

What do I tell them? Do I reassure them with tales of heaven—that their father is now safe in heaven? Do I tell them that no matter what happens to their poor fragile flesh there is a safe place for them in heaven?

What I want to tell them is that their final destination is not heaven, but memory. And you can make of yourself a memory so profound that it transforms everything it touches.

My Evie screams, her face a mask of blood, and Tom looks even worse—all I can see through the red confusion of his face is a single fixed eye. I try to run, then, to separate them, but I am so awkward and pathetic I fall into the brush and tangle below them, where I sprawl and cry out in sorrow and agony.

Only then do they stop, and they come to me, my grandchildren, to stare down at me silently, their faces solemn. Tom has wiped much of the blood from his face to reveal the scratches there, the long lines and rough shapes like a child’s awkward sketch.

This is my legacy, I think. These are the ones who will keep me alive, if only as a memory poorly understood, or perhaps as a ghost too troublesome to fully comprehend.

We try and we try but we cannot sculpt a shape out of what we’ve done in the world. Our hands cannot touch enough. Our words do not travel far enough. For all our constant waving we still cannot be picked out of a crowd.

My grandchildren approach for the end of my story. I can feel the terrible swiftness of my journey through their short lives. I become a voice clicking because it has run out of sound. I become a tongue silently flapping as it runs out of words. I become motionless as I can think of nowhere else to go.

I become the stone and the plank and the empty field. I am really quite something, the monster made in their image, until I am scattered, and forgotten.

CHAPTER SIX

STEPHEN GRAHAM JONES

They were eighty miles from campus, if miles still mattered.

It had been Dr. Ormon’s idea.

Dr. Ormon was Crain’s dissertation director. If dissertations still mattered.

They probably didn’t.

Zombies. Zombies were the main thing that mattered these days.

Crain lowered his binoculars and turned to Dr. Ormon. “They’re still following 95,” he said.

“Path of least resistance,” Dr. Ormon said back.

The clothes Crain and Dr. Ormon were wearing, they’d scavenged from

a home that had had the door flapping, the owners surely scavenged on themselves, by now.

Dr. Ormon’s hair was everywhere. The mad professor.

Crain was wearing a paisley skirt as a cape. His idea was to break up the human form, present a less enticing silhouette. Dr. Ormon said that was useless, that the zombies were obviously keying on vibrations in the ground; that was part of why they preferred the cities, and probably had a lot to do with why they were sticking mostly to the asphalt, now: they could hear better through it.

Crain respectfully disagreed. They didn’t prefer the cities, it was just that the zombie population was mimicking preplague concentrations. Whether walking or just lying there, you would expect the dead to be pretty much where they died, wouldn’t you?

Instead of entertaining the argument, Dr. Ormon ended it by studying the horde through their one pair of binoculars, and noting how, on asphalt, there was no cloud of dust to announce the zombies’ presence.

Sophisticated hunting techniques? A rudimentary sense of self and other?

“Do horde and herd share a root?” Crain asked.

He’d been tossing it back and forth in his head since the last exit.

“We use horde for invaders,” Dr. Ormon said, in his thinking-out-loud voice. “Mongols, for example.”

“While herd is for ungulates, generally.”

“Herd mentality,” Dr. Ormon said, handing the binoculars back. “Herd suggests a lack of intelligence, of conscious thought, while horde brings with it aggressiveness. Or, at the very least, a danger to the society naming those invaders.”

Inferno

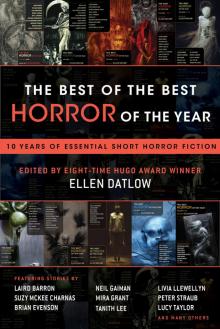

Inferno The Best of the Best Horror of the Year

The Best of the Best Horror of the Year When Things Get Dark

When Things Get Dark A Whisper of Blood

A Whisper of Blood Echoes

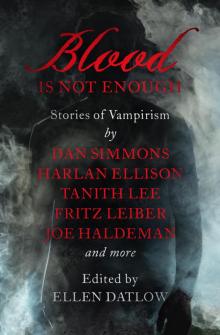

Echoes Blood Is Not Enough

Blood Is Not Enough Haunted Nights

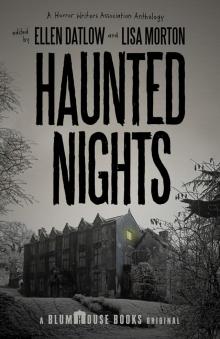

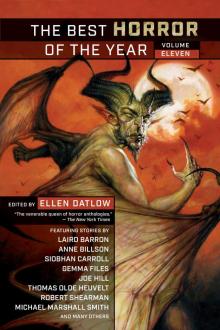

Haunted Nights The Best Horror of the Year Volume Eleven

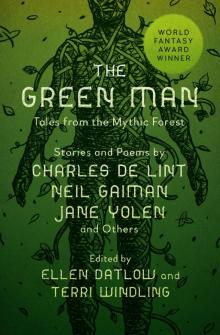

The Best Horror of the Year Volume Eleven The Green Man

The Green Man The Dark

The Dark Mad Hatters and March Hares

Mad Hatters and March Hares Nebula Awards Showcase 2009

Nebula Awards Showcase 2009 The Devil and the Deep

The Devil and the Deep