- Home

- Ellen Datlow

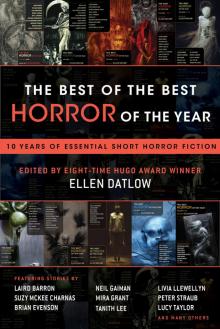

The Best of the Best Horror of the Year Page 15

The Best of the Best Horror of the Year Read online

Page 15

Then no, the two words only sounded similar.

Crain could accept this. Less because he had little invested in a shared etymology, more because the old patterns felt good, felt right: teacher, student, each working toward a common goal.

It was why they were here, eighty miles from campus.

There had been families to return to, of course, but, each being a commuter, their only course of action had been to hole up in the long basement under the anthropology building. The break-room refrigerator could only sustain two people for so long, though.

Crain tried to frame their situation as a return to more primitive times. What the plague was doing, it was resetting humanity. Hunting and gathering were the order of the day, now, not books or degrees on the wall. Survival had become hand-to-mouth again. There was to be no luxury time for a generation or two, there would be no specializing, no social stratification. The idea of a barter economy springing up anytime soon was a lark; tooth and nail was going to be the dominant mode for a while, and only the especially strong would make it through to breed, keep the species going.

Dr. Ormon had taken Crain’s musings in as if they were idle ramblings, his eyes cast to the far wall, but then he had emerged from their latrine (the main office, ha) two days later with a decidedly intense cast to his features, his eyes nearly flashing with discovery.

“What?” Crain had said, suddenly sure a window had been breached.

“It does still matter,” he said. “All our—this. Our work, our studies, the graduate degrees. It’s been a manual, a guide, don’t you see?”

Crain studied the map of Paleo-America tacked on the wall and waited.

This was Dr. Ormon’s style.

“Your chapter two,” Dr. Ormon went on. “That one footnote … it was in the formative part, the foundational prologue. The part I may have said felt straw-mannish.”

“The name dropping,” Crain filled in.

Now that it was the postapocalypse, they could call things what they were.

“About the available sources of protein.”

Crain narrowed his eyes, tried to feel back through his dissertation.

Chapter two had been a textual wrestling match, no doubt.

It was where he had to address all the mutually exclusive claims for why the various and competing contenders for the title of man on the African savanna had stood up, gone bipedal.

Crain’s thesis was that a lack of body hair, due to the forest’s retreat, meant that the mothers were having to carry their infants now, instead of letting them hang on. They had no choice but to stand up.

Part and parcel with this was the supposition that early man—a grand word for a curious ape with new wrist and pelvis morphology—was a persistence hunter, running its prey down over miles and days. Running it to death.

A lifestyle like this would require the whole troop—the proper word for a group of apes was a shrewdness, but Crain had always thought that a poor association for gamblers and inventors—to be on the move. No posted guards, no beds to return to, thus no babysitters like jackals had, like meerkats had, like nearly all the other mammalian societies had.

This meant these early would-be humans had to take their babies with them, each chase. They had to hold them close as they ran. Hold them with hands they could no longer devote to running.

It was elegant.

As for how these mutant bipeds were able to persistence hunt so effectively, it was those unheralded, never-seen-before sweat glands, those cavernous lungs, the wide nostrils. What was nice for Crain’s argument was that this was all work others had already done. All he had to do was, in chapter two, organize and cite, bow and nod.

But, this being anthropology, and the fossil record being not just sparse but cruelly random, alternate theories of course abounded.

One was the water-ape hypothesis: we got the protein to nourish our growing brains and lengthen our bones from shellfish. Droughts drove us to the shores of Africa, and what initially presented itself as a hurdle became a stepping stone.

Another theory was that our brains grew as self-defense mechanisms against the up-and-down climate. Instead of being allowed to specialize, we had to become generalists, opportunists, our brains having to constantly improvise and consider options, and, in doing so, that accidentally give birth to conceptual thought.

Another theory was that that source of brain-growing protein had been on the savanna all along.

Two days after Dr. Ormon’s eureka moment, Crain shouldered open the door to their basement for the last time, and they went in search of a horde.

It didn’t take long. As Crain had noted, the preapocalypse population of their part of New Hampshire had already been dense; it stood to reason that it still would be.

Dr. Ormon shrugged it off in that way he had that meant their sample was too limited in scope, that further studies would prove him out.

To his more immediate academic satisfaction, though—Crain could feel it wafting off him—when a horde presented itself on the second day (the smell), the two of them were able to hide not in a closet (vibration-conducting concrete foundation) or under a car (asphalt …), but in a shrub.

The comparatively loose soil saved them, evidently. Hid the pounding of their hearts.

Maybe.

The horde had definitely shuffled past, anyway, unaware of the meal waiting just within arm’s reach.

Once it had been gone half a day, Crain and Dr. Ormon rose, scavenged the necessary clothes, and followed.

As Crain had footnoted in chapter two of his dissertation, and as Dr. Ormon had predicted in a way that brooked no objection, the top predators in any ecosystem, they pull all the meat from their prey and move on. Leaving niches to be filled by the more opportunistic.

In Africa, now, that was hyenas, using their powerful jaws to crack into gazelle bones for the marrow locked inside.

Six million years ago, man had been that hyena.

“Skulking at the fringes has its benefits,” Dr. Ormon had said.

In this case, those fringes were just far enough behind the horde that the corpses it left behind wouldn’t be too far into decay yet.

I-95 was littered with the dead. The dead-dead, Crain christened them. As opposed to the other kind. A field of skeletons scummed with meat and flies, the bones scraped by hundreds of teeth, then discarded.

Crain and Dr. Ormon had stood over corpse after corpse.

Theory was one thing. Practice was definitely another.

And—they talked about it, keeping their voices low—even the ones with enough meat hidden on a buttocks or calf to provide a meal of sorts, still, that meat was more than likely infected, wasn’t it?

Their job as survivors, now, it was to go deeper than that infection.

This is how you prove a thesis.

Once it was dark enough that they could pretend not to see, not to know, they used a rock to crack open the tibia of what had once been a healthy man, by all indications. They covered his face with Crain’s cape, and then covered it again, with a stray jacket.

“Modern sensibilities,” Dr. Ormon narrated. “Our ancestors would have had no such qualms.”

“If they were our ancestors,” Crain said, something dark rising in his throat.

He tamped it down, just.

The marrow had the consistency of bubble gum meant for blowing bubbles, after you’ve chewed it through half the movie. There was a granular quality, a warmth, but no real cohesion anymore. Not quite a slurry or a paste. More like an oyster just starting to decompose.

Instead of plundering the bone for every thick, willing drop, they each took a meager mouthful, closed their eyes to swallow.

Neither threw it back up.

Late into the night, then, they talked about how, when man had been living on marrow like this—if he had been, Dr. Ormon allowed, as one meal doesn’t an argument prove—this had of course been well before the discovery and implementation of fire. And fire of course was what ma

de the meat they ate easier to digest. Thus their guts had been able to shrink.

“That’s what I’m saying,” Crain said, piggybacking on what was becoming Dr. Ormon’s research. “Persistence hunters.”

“You’re still attached to the romantic image of them,” Dr. Ormon said, studying something under his fingernail, the moonlight not quite playing along. “You have this image of a Zulu warrior, I think. Tall, lean. No, he’s Ethiopian, isn’t he? What was that Olympic runner’s name, who ran barefoot?”

“A lot of them do,” Crain said, staring off into the trees. “But can we digest this, do you think?” he said, touching his stomach to show.

“We have to,” Dr. Ormon said.

And so they did. Always staying a half day behind the horde, tipping the leg bones up for longer and longer draughts. Drinking from the tanks of toilets they found along the way. Fashioning turbans from scraps.

The smarter among the crows began to follow them, to pick at these splintered-open bones.

“Niches and valleys,” Dr. Ormon said, walking backward to watch the big black birds.

“Host-parasite,” Crain said, watching ahead, through the binoculars.

“And what do you think we are?” Dr. Ormon called, gleefully.

Crain didn’t answer.

The zombies at the back of the horde—Crain still preferred herd, in the privacy of his head—he’d taken to naming them. The way a primatologist might name chimpanzees from the troop she was observing.

There was Draggy, and Face B. Gone, and Left Arm. Flannel and Blind Eye and Soup.

By the time they got to the horde’s victims, there was rarely anything left but the bones with their precious marrow that Dr. Ormon so needed, to prove Crain’s second chapter was in need of overhaul, if not reconception altogether.

That night, over a second tibia he’d taken to holding like a champagne flute—Dr. Ormon somehow affected a cigar with his ulnas—Crain posed the question to Dr. Ormon: “If a species, us, back then, adapts itself to persistence hunting—”

“If,” Dr. Ormon emphasized.

“If we were adapting like that, then why didn’t the prey one-up us?”

Silence from the other side of what would have been the campfire, if they allowed themselves fires. If they needed to cook their food.

These were primitive times, though.

In the darkness, Dr. Ormon’s eyes sparked. “Gazelles that can sweat through their skin, you mean,” he said. “The better to slip our grasp. The better to run for miles.”

“The marathon gazelle,” Crain added.

“Do we know they didn’t?” Dr. Ormon asked, and somehow in the asking, in the tone, Crain sensed that Dr. Ormon was forever objecting not to him, Crain, or to whatever text he was engaging, whatever panel he was attending, but to someone in his life who called him by his first name, whatever that was. It was an unasked-for insight.

“Mr. Crain?” Dr. Ormon prompted.

This was the classroom again.

Crain nodded, caught up. “What if the gazelles of today are, in comparison to the gazelles of six million years ago, marathon gazelles, right?”

“Excellent.”

Crain shook his head what he hoped was an imperceptible bit. “Do you think that’s the case?” he asked. “Were we that persistent a hunter?”

“It’s your thesis, Mr. Crain.”

Crain gathered his words—he’d been running through this argument all day, and Dr. Ormon had stepped right into the snare—said, as if reluctantly, as if only just thinking of this, “You forget that our persistence had rewards, I think.”

It had a surely-you-jest rhythm to it that Crain liked. It was like speaking Shakespeare off the cuff, by accident. By natural talent.

“Rewards?” Dr. Ormon asked.

“We persistence hunted until that gave us enough protein to—to develop the necessary brain capacity to communicate. And once we started to communicate, tricks of the trade started to get passed down. Thus was born culture. We graduated out of the gazelle race before the gazelles could adapt.”

For long, delicious moments, there was silence from the other side of the noncampfire.

Has the student become the master? Crain said to himself.

Does the old silverback reconsider, in the face of youth?

He was so tired of eating stupid marrow.

Just when it seemed Dr. Ormon must have retreated into sleep, or the understandable pretense of it—this was a new world, requiring new and uncomfortable thinking—he chuckled in the darkness, Dr. Ormon.

Crain bored his eyes into him, not having to mask his contempt.

“Is that how man is, in your estimation?” Dr. Ormon asked. “Or, I should say, is that how man has proven himself to be, over his short tenure at the top of this food chain?”

Crain didn’t say anything.

Dr. Ormon didn’t need him to. “Say you’re right, or in the general area of right. Persistence hunting gave us big brains, which gave us language, which gave us culture.”

“Chapter six,” Crain said. “When I got to it, I mean.”

“Yes, yes, as is always the case. But humor me aloud, if you will. Consider this your defense. Our ancient little grandfathers, able to sweat, lungs made for distance, bipedalistic for efficiency, their infants cradled in arms, not having to grasp at hair like common chimpanzees—”

“I never—”

“Of course, of course. But allowing all this. If we were so successful, evolving in leaps and bounds. Tell me then, why are there still gazelles today? Agriculture and the fabled oryx are still thousands of generations away, here. What’s to stop us from plundering the most available food source, unto exhaustion?”

Time slowed for Crain.

“You can’t, you can’t ever completely—”

“Eradicate a species?” Dr. Ormon completed, his tone carrying the obvious objection. “Not that I disagree about us moving on to other food sources eventually. But only when necessary, Mr. Crain. Only when pressed.”

“Chapter six,” Crain managed.

“Pardon?”

“I would have addressed this in chapter six.”

“Good, good. Perhaps tomorrow you can detail how, for me, if you don’t mind.”

“Sure, sure,” Crain said. And: “Should I just keep calling you doctor?”

Another chuckle, as if this question had already been anticipated as well.

“Able,” Dr. Ormon said. “After my father.”

“Able,” Crain repeated. “Crain and Able.”

“Close, close,” Dr. Ormon said, dismissing this conversation, and then cleared his throat for sleep as was his practice, and, in his mind’s eye, Crain could see the two of them from above, their backs to each other, one with his eyes shut contentedly, the other staring out into the night.

Instead of outlining chapter six the next day, Crain kept the binoculars to his face.

If he remembered correctly, 95 crossed another major highway soon.

Would the herd split, wandering down separate ways, or would they mill around indecisively, until some Moses among them made the necessary decision?

It was going to be interesting.

He might write a paper on it, if papers still mattered.

And then they walked up on the most recent group of victims.

They’d been hiding in an RV, it looked like.

It was as good as anywhere, Crain supposed. No hiding place or perfect fortress really worked.

It looked like this group had finally made their big run for it. The RV’s front tires were gummed up with zombies. They’d had no choice but to run, really. It was always all that was left, right at the end.

They made it about the usual distance: thirty feet.

They’d been gnawed down to the bone in places, of course.

“If they ever figure out there’s marrow in there,” Dr. Ormon said, lowering himself to a likely arm, its tendons bare to the sun for the first time.

“They don’t have language,” Crain said. “It would just be one knowing, not all of them.”

“Assuming they speak as you and I do, of course,” Dr. Ormon said, wrenching the forearm up.

The harsh creaking sound kickstarted another sound.

In a hiking backpack lying across the center stripe, there was what could only be an infant.

When it cried, it was definitely an infant.

Crain looked to Dr. Ormon, and Dr. Ormon looked ahead of them.

“It’s right on the asphalt,” Dr. Ormon said, his tone making this an emergency.

“They go by smell,” Crain said. “Or sound. Just normal sound, not conductive.”

“This is not an argument either of us wants to win,” Dr. Ormon said, stepping neatly over to the backpack and leaning forward onto it with both knees.

The crying muffled.

“We’re re-enactors,” he said, while doing it, while killing this baby. “My brother-in-law was a Civil War soldier on weekends. But this, this is so much more important. An ancient script, you could say. One written by the environment, by biology. Inscribed in our very instincts.”

Crain watched, and listened, his own plundered tibia held low along his right leg.

Soon enough, the cries ceased.

“You can test your theory about—about methods of child transport—later,” Dr. Ormon said, rising up to drive his knees down one last, terrible time. For emphasis, it seemed.

“That was probably Adam,” Crain said, looking down at the quiet lump in the backpack.

“If you believe the children’s stories,” Dr. Ormon said, casting around for his ulna. He claimed their flavor was slightly headier. That it had something to do with the pendulum motion they’d been subjected to, with a lifetime of walking. That that resulted in more nutrients getting trapped in the lower arms.

Crain didn’t care.

He was still staring at the raspy blue fabric of the backpack, and then he looked up the road as well.

Left Arm was watching them.

He’d come back. The sound had traveled along the asphalt ribbon of 95 and found him, bringing up the rear of the horde.

It hadn’t been scent or pressure waves in the air, anyway; the wind was in Crain’s face, was lifting his ragged cape behind him.

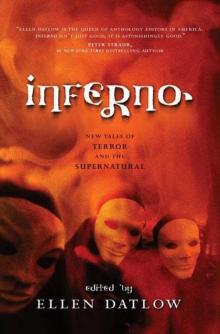

Inferno

Inferno The Best of the Best Horror of the Year

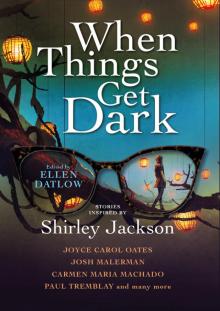

The Best of the Best Horror of the Year When Things Get Dark

When Things Get Dark A Whisper of Blood

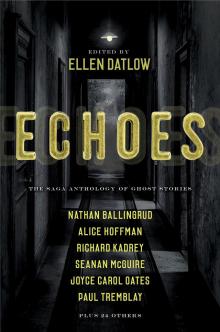

A Whisper of Blood Echoes

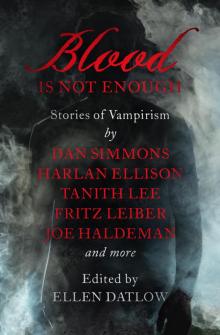

Echoes Blood Is Not Enough

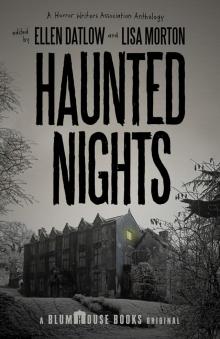

Blood Is Not Enough Haunted Nights

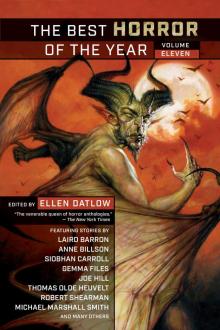

Haunted Nights The Best Horror of the Year Volume Eleven

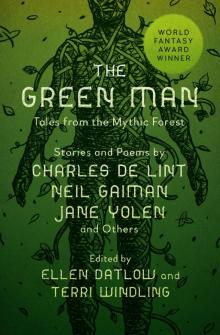

The Best Horror of the Year Volume Eleven The Green Man

The Green Man The Dark

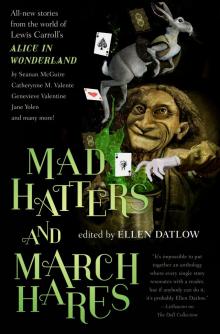

The Dark Mad Hatters and March Hares

Mad Hatters and March Hares Nebula Awards Showcase 2009

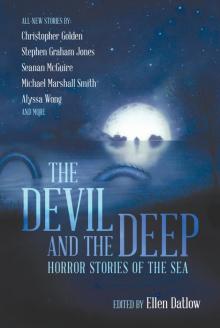

Nebula Awards Showcase 2009 The Devil and the Deep

The Devil and the Deep